- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

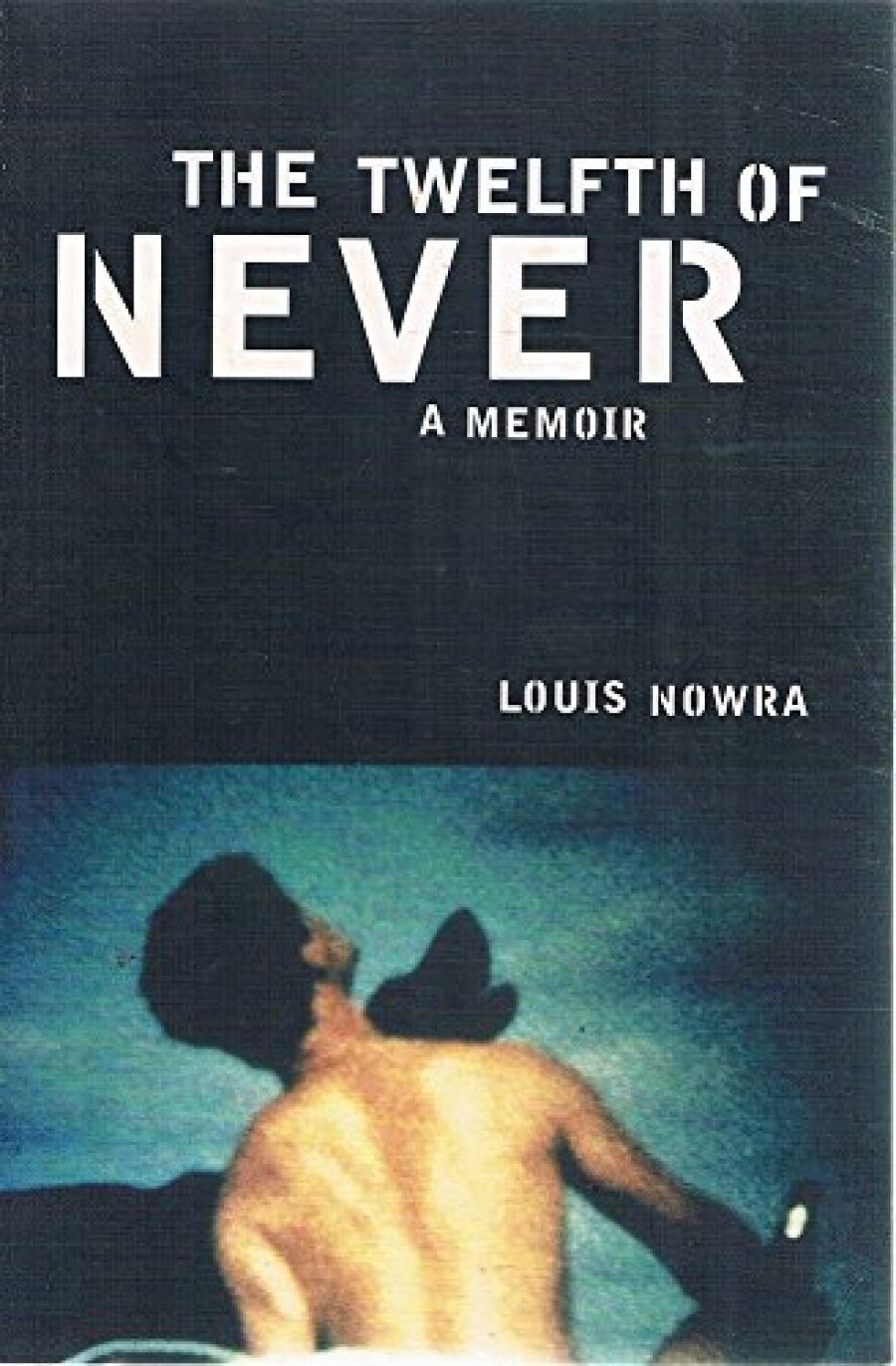

- Custom Article Title: David McCooey reviews 'The Twelfth of Never: A memoir' by Louis Nowra

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Louis Nowra was born in 1950 and is – as he presents himself in this memoir – that very mid-century thing, an outsider. An outsider in terms of class, mental constitution, and sexuality (for a time), Nowra suffers a worse, and originary, alienation from his mother. Being born on the fifth anniversary of his mother’s shooting of her father ...

- Book 1 Title: The Twelfth of Never

- Book 1 Subtitle: A memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $25 pb, 377 pp, 0330361872

But like many interesting autobiographies, The Twelfth of Never confounds these notions by being both too original and too conventional. Despite bookending his narrative with his mother’s traumatic story, Nowra is little interested in formal novelty. Tracing his development from the extended family, through parents, school self, and post-university, differentiated self is utterly conventional. But many of the stories and characters within this template are decidedly odd. This is partly because so much of the story is concerned with violence and madness. The mother in The Twelfth of Never is frankly brutal. An intelligent, almost pathologically angry woman, she causes her son to retreat emotionally in a way that prefigures Nowra’s greater alienation: the alienation of the self from the self.

Narrated in a more or less neutral tone, The Twelfth of Never suggests that the apparent normality of Nowra’s world was one of its oddest aspects. Perhaps it’s not surprising that as a boy he should have believed that aliens from outer space could inhabit human bodies. The evidence of the oddity of this world is not only in the madness (in grandparents, and a strange habit of living near asylums), but also Nowra’ s own experiences: his erotic attraction to the amputated arm of a schoolgirl from Holland; his boyhood admiration for Adam Clayton Powell (an African-American, slightly dodgy politician); the neurological complications from a nasty head injury; his transvestite lover; and his simultaneously scholarly and reckless interest in natural hallucinogens (we’ve reached the 1970s by now).

It seems hardly surprising that this outsider figure should partly respond to the more violent episodes of his life through psychic disassociation. Again and again, Nowra describes moments of extreme psychic pressure – usually to do with violence – in which he becomes a spectator to himself. This reaches a climax when he engages a young male friend in sexual activity, ‘not even aware I was going to ask the question until I heard myself saying it’. The self-alienated self is also seen in Nowra’s mimicry of his friends’ gestures, accents, and even walks, making him a kind of antipodean Peter Sellers in short pants. Certainly, the link between alienation and theatricality is explicit.

The importance of the theatre, however, is not overplayed. Indeed, while Nowra narrates some important incidents in his move toward becoming a playwright, and while he makes some connections with his plays and other writings, he almost never mentions his works by name. We are left to make the connections for ourselves: between his first experience of directing, in an asylum, with Così; his interest in the exotic with many of his plays’ locations; the interest in powerful women with The Precious Woman and so on.

Estrangement, of course, is a key source of theatrical power, but much of the theatricality here is cast in a questionable light, especially in the way that it emanates from a dysfunctional family. Nowra’s mother is a classic ageing diva, raging against time and her romantic disappointments. Nowra’s misanthropic, hotelier grandfather is Dickensian in his amused, cynical viewing of his drunken patrons being entertained by fighting (also drunken) dwarfs.

The Twelfth of Never is good on sex, anxiety, obsession, and the need for escape, all central tropes of the autobiography of childhood and youth (and outsider narratives generally). At times, Nowra’s humorous tone is reminiscent of Clive James’s Unreliable Memoirs or Robin Wallace-Crabbe’s A Man’s Childhood (both classics in their own way), but, unlike these works, The Twelfth of Never suffers from a lack of artfulness, at least the artfulness of brevity. Too many incidents are narrated with tiring copiousness. This autobiography, then, might seem either too contrived or not contrived enough. This might be said of much of Nowra’s work. Does the work’s mix of extremity and ordinariness make it unreal? In Inside the Island, Nowra observes that, ‘It is always a mistake to believe that just because behaviour is extreme it is unreal.’ This is a good rubric to keep in mind when reading The Twelfth of Never, a book that stays with you long after you thought you had finished with it. This itself is a marker of a strange power, perhaps the unsettling, ambiguous power of the outsider.

Comments powered by CComment