- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Non-fiction

- Custom Article Title: Foster's art of excess

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Foster's art of excess

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When applied to art and literature, the word ‘serious’ can be used to suggest a work is substantial and important, not necessarily that it is the opposite of humorous. There is a sense in which Rabelais and Cervantes are serious writers. But the slippage between these two meanings – the fact that our language permits a casual conflation of worthiness and sincerity – reflects a long-standing cultural prejudice which relegates comedy to a second tier, as if a talent for provoking laughter were somehow less praiseworthy than a talent for inspiring pity and terror. Tragedy is often assumed to be profound and ennobling, but comedy’s levelling tendencies, the anarchic implications of mockery and unbridled laughter, are apt to be viewed with suspicion.

- Book 1 Title: David Foster

- Book 1 Subtitle: The satirist of Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: Cambria Press, US$94.95 hb, 246 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

More importantly, Lever’s study provides an insightful and accessible introduction to a writer whose work is both difficult and underappreciated. Unlike many of the novelists who established themselves in the 1970s – Peter Carey, Frank Moorhouse, Helen Garner, David Malouf – Foster still languishes in something close to obscurity, despite having penned one of the more outrageously inventive bodies of work in Australian literature. In his preface to Lever’s book, the critic Andrew Riemer laments the neglect to which this highly talented and idiosyncratic novelist has suffered at the hands of his countrymen. Foster has had his prominent supporters, of course, including Riemer and the dedicatees of Lever’s book, Geoffrey Dutton and Helen Daniel, but he remains a living example of the fact that a writer can carry off this nation’s major literary prize – he won the Miles Franklin Award in 1997 for The Glade Within The Grove (1996) – and still fail to gain lasting recognition beyond the narrow confines of the literati. Citing the examples of European enfants terribles, the French novelist Michel Houellebecq and the Austrian Elfriede Jelinek, both of whom are savage critics of their respective countries but enjoy wide recognition, Riemer wonders why Foster’s no less provocative work has not generated a comparable reaction, and chalks it up to Australia’s cultural immaturity. (Yes, Foster gives his characters names like Roland Rocca, Noel Horniman and Mike Hock, and we are immature.) But the reasons for Foster’s marginalisation have as much to do with the formal adventurousness of his novels and the ambiguities they cultivate.

Foster is, in Lever’s words, ‘the most original, challenging, contradictory, risk-taking, and infuriating novelist of his generation’. He is possibly the least serious writer Australia has ever produced. His books are, as Lever points out, Menippean satires – what Northrop Frye called ‘anatomies’ – the defining features of which are a mixing of styles, a fondness for digression, a tendency toward encyclopedic inclusiveness, a collision of the highest erudition with the lowest of low humour. This is, in other words, a category of literary misfits, of works which do not slot neatly into categories. Satirists do not write to make friends, but the very form of Foster’s work places great demands upon the reader.

I cannot claim to have read Jelinek, but Houellebecq’s novels, rendered in hilariously mordant deadpan prose, go about their work by being blandly offensive; Foster’s fiction is a far headier brew. He is ‘a novelist of ideas rather than character’. His art is one of excess. His fiction tends to be sprawling and complex, working by accretion rather than straight-ahead plotting; his prose can be richly and vulgarly demotic. As Lever suggests in her discussion of Plumbum (1983), a novel with some pointed things to say about the way Australia treats its artists, an element of risk is an important part of his technique. She likens it to jazz, in its emphasis on spontaneity and improvisation (Foster’s lengthy curriculum vitae includes a stint as a jazz drummer). But most importantly, as Riemer has pointed out, Foster’s novels, by veering between sharp-witted critique and irreverence, send out mixed signals about their seriousness.

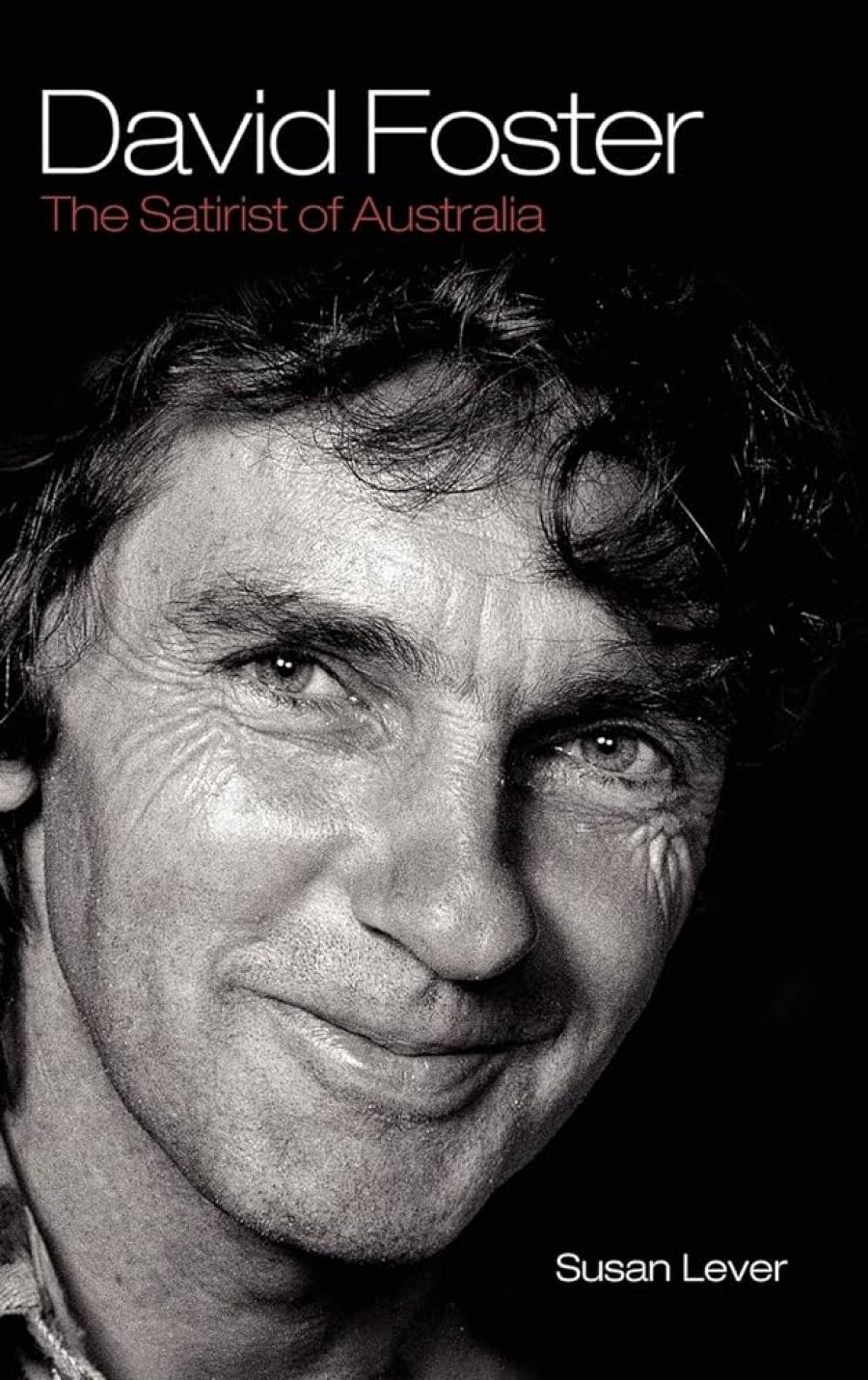

Both Lever and Riemer compare Foster to Patrick White, but White, even for those who do not read him, at least presents a recognisable persona of a serious literary author. Think of the later images of the patrician White, his long face and downturned mouth radiating disapproval at levels sufficient to sterilise surgical instruments. Compare this to the cheeky bastard with a twinkle in his eye who stares out from the cover of Lever’s book, and you will have a sense of Foster’s image problem. Sure, he might shout you a beer, but you’re going to be on the wrong end of some serious piss-taking for the rest of the afternoon. Despite our national self-image as a bunch of larrikins, Australians are, by and large, a compliant lot. Give us a genuine larrikin – a scabrous and scarily smart ex-postman from the hinterlands with a PhD in Chemistry, a black belt in tae kwon do, a penchant for citing Juvenal in the original Latin, and a special relationship with a Jersey cow named Solange – and we don’t quite know what to make of him.

The desire to be confronting and unsettling is fundamental to Foster’s art. In his essay on ‘Satire’, he writes that the aim is to ‘draw blood’, and defines a satirist as ‘a man abundantly over-endowed with aggressive impulses, who must choose an acceptable social form for those impulses’. He suggests that cultivating a divided nature is an essential part of this process. ‘The most effective way to satirise something,’ he observes, ‘is to be the thing you’re satirising.’ But at the same time, he insists it is also necessary for the satirist to hold himself apart from the object of his ridicule. His work should express ‘a sense of moral outrage’ and contain ‘explicit authorial comment’ that distinguishes it from its target. Thus the satirist must ‘split himself down the middle, with one half laughing at the other’.

It is this divided, contradictory quality to Foster’s work that most interests Lever. It is a commonplace that one has only to scratch a satirist to find a moralist, but she argues that Foster’s work lacks any clear reformist agenda. His stance is ‘both radical and conservative’. He is committed to ‘a white, male, individualist art’, what he has described as the ‘uniquely masculine form’ of satire, but his ‘habit of mind is critical and inclined to seek the alternative or contrary view to any assumption’. Foster’s work proceeds from a conviction that society is in terminal decline, but Lever proposes that the central thematic tension running through his novels is between an enlightenment rationalism and an interest in religion and mysticism. His early novel Moon-lite (1981), she argues, ‘holds up every belief system to mockery; but it finds belief systems worth pursuing’. As one character puts it: ‘Gotta hold two views at once.’

The example of Jonathan Swift would suggest that an occupational hazard for the dedicated chronicler of human folly is misanthropy. Similarly, to adopt a stance wholly at odds with one’s society, to have the chutzpah to diagnose one’s entire civilisation as decadent and doomed, can become indistinguishable, in a certain light, from the stance of a crank and a reactionary. Foster himself has asked, even more starkly: ‘how can a reader distinguish the work of a psychopath from that of a satirist?’ Now, it is possible to be both a crank and a brilliant novelist at the same time (witness Dostoevsky), but even Lever, near the end of her study, baulks at some of Foster’s more flamboyant assertions about women and homosexuality.

Lever considers the dissection of masculine rites in Mates of Mars (1991) to be his most fully realised work, preferring it to the more celebrated The Glade Within The Grove. This is partly because she reads the latter in conjunction with a fascinating but slightly weird essay on ‘Castration’ – which can be found in Studs and Nogs: Essays 1987–1998 (1999) – as endorsing the novel’s cult of tree-worshipping castrati rather more seriously (there’s that word again) than one might reasonably hope. This leads her to muse about ‘artistic achievements wrought on the basis of eccentric and unpalatable theories, like Yeats’s later poetry’. But she is right to emphasise that one of the chief virtues of Foster’s writing is his willingness to push ideas to their limit. He needs to ‘be seen as performing satire through a range of personae, including one called “David Foster” who sometimes writes essays or speaks at literary festivals and conferences’. He is not alone among serious writers in that ‘the qualities that make Foster difficult are, of course, also those which make his books rewarding to read’.

Comments powered by CComment