- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: A very easeful death

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A very easeful death

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

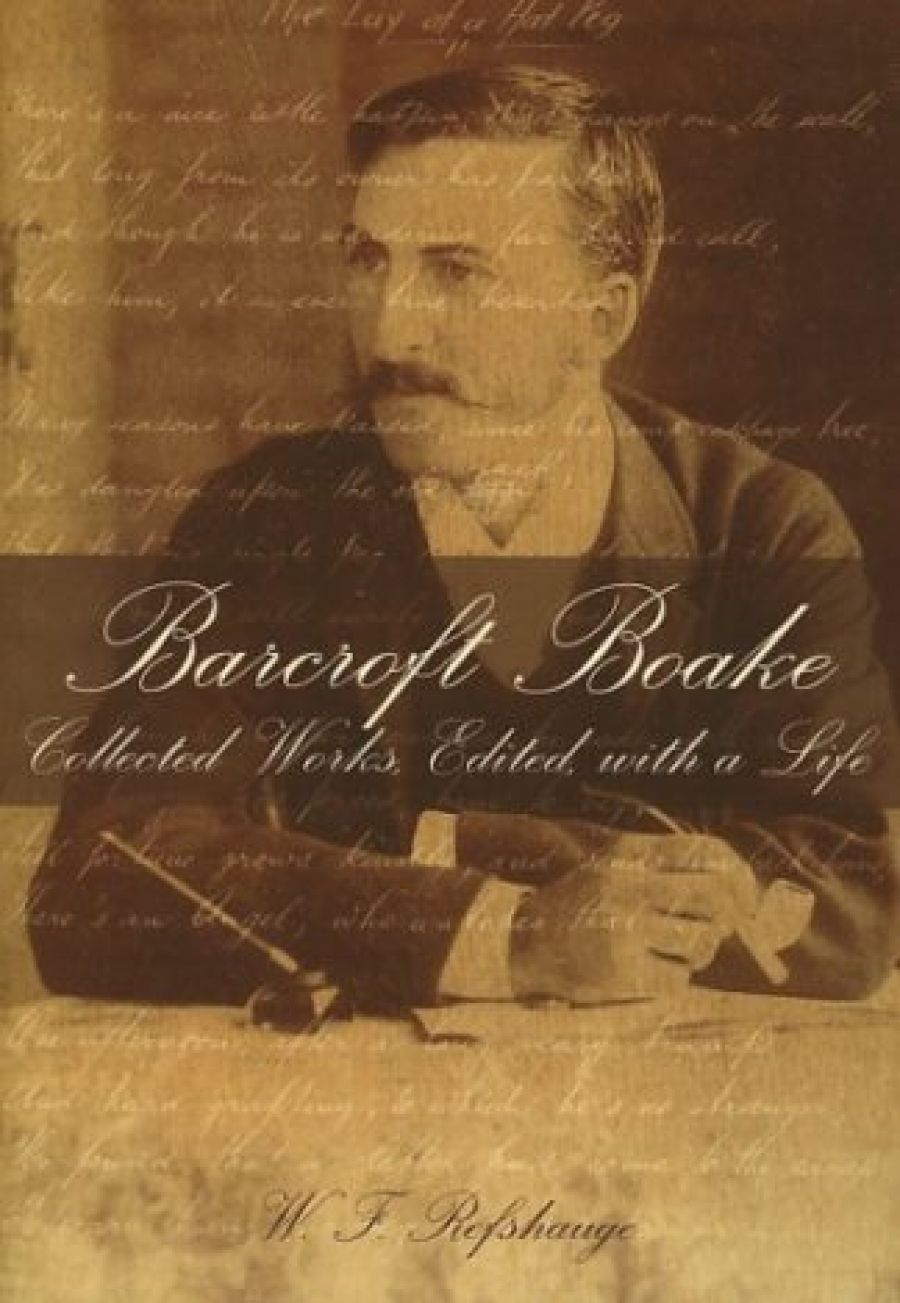

Barcroft Boake is remembered as one of the lesser lights in the school of Bush poets publishing in the Sydney Bulletin in the late nineteenth century. Two facts are probably known to most people who have heard of him: that he wrote a gloomy but impressive and memorable poem, much anthologised, called ‘Where the Dead Men Lie’, and that he hanged himself with his stock-whip when young. (Some, mindful of Keats, might guess he was twenty-six when he died, and they would be right.)

- Book 1 Title: Barcroft Boake

- Book 1 Subtitle: Collected works, edited, with a life

- Book 1 Biblio: Australian Scholarly Publishing, $39.95 pb, 309 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The legend of the tragic young bush poet – Adam Lindsay Gordon in a minor key – was thus early established by Stephens, who also gave Boake’s career an explicitly national dimension, calling him, in 1907, ‘the man who more strongly than any other has poetically embodied the characteristic spirit of Australia’. That Stephens had already compared him to Keats, in a puff-piece for his 1897 edition, points to a sustained myth-making impulse on his part.

Bill Refshauge’s ‘Collected Works, Edited, with a Life’ – a pleasingly old-fashioned combination of functions – does not set out to shatter the Boake legend, such as it is. In focusing quite closely (in the ‘Life’) on elucidating Boake’s personality and his relationships, Refshauge somewhat demystifies his status as a cultural icon, though he also confirms its ‘authenticity’ by showing that, unlike many of the ‘bush poets’ of the time, Boake actually lived and worked in the bush. The ‘Life’ section, in any case, is quite short and the rest of the commentary is devoted to a detailed account of editorial methods, reflections and decisions spread across a fourteen-page editorial note, forty pages of notes on individual poems, and an unnecessarily discursive ten-page chronological work list. A two-page chronology of Boake’s life would surely have been more useful than this, as would several more word glosses and historical annotations. The edition is strangely short on helpful information on individual poems, while going somewhat overboard on textual matters.

The arrangement of the poems is far from simple. Mindful of uncertainties about the chronology of composition, Refshauge has made the slightly odd decision to present the poems in two separate series: the first comprising only those poems that were published in Boake’s lifetime (in order of publication); the second comprising those that were first published in Stephens’s two posthumous editions, together with various pieces selected from the notebooks, in prose and verse, which were never published (but which seem to be complete) – these in a somewhat speculative chronological order. I was unconvinced of the merits of this ultra-careful arrangement: a single, if at times approximate, chronological sequence is so obviously and straightforwardly useful for getting a sense of poetic development that it seems a great pity to forgo it.

An interesting effect of the double series is the strong impression it conveys of the overwhelming preponderance of a single theme in Boake’s work: death. This is, of course, the subject of his most famous poem, but it is also the theme, or at least the central fact, of most of the poems in the first series: deaths by thirst or starvation, drowning or shooting, madness or a broken heart, or falling drunk under the wheels of a coach, to name but a few. Even a comic poem such as ‘Babs Malone’, where a two-year-old baby accidentally rides a horse to victory, is shadowed by the imminence of death. Yet for all that, Boake’s poetry is often a delight to read. Poems such as ‘Jimmy Wood’ and ‘Fogarty’s Gin’, in particular, show a surprising delicacy of tone, and the metrical virtuosity which is his most distinctive quality is evident throughout the series (and might have received more comment in the notes).

The second series is less obsessively focused, and even though the quality is more uneven, these poems convey more of a sense of Boake as a fully rounded social being, an affectionate son and sibling, and an entertaining companion. It does seem, though, that in his life and not just in his poetry, he was considerably more than ‘half in love with easeful death’. His bouts of depression, adulation of Gordon, and suicide references in letters all point in this direction, as also – most strikingly – does the bizarre mock-hanging he and a friend performed at a party, in which he nearly succeeded in killing himself. Less than four years later he did succeed, but not without leaving a rich legacy.

Comments powered by CComment