- Free Article: No

- Custom Article Title: Cursory romance

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Cursory romance

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Murray Bail’s fiction inhabits a curious space. Despite its attention to the detail of the rural landscape, the ‘endless paddocks and creaking tin roofs’, it is not, in any meaningful sense, realist, either in its intention or its execution. Instead, against carefully created backdrops, it weaves something closer to fairy tales, looping meditations on the power of story, and love, whose affinities lie – for all that many of Bail’s world of pastoralists who dress for dinner and unmarried daughters wilting in the Australian emptiness sometimes might not seem out of place in Patrick White – with distinctly un-Australian writers such as Calvino, Borges and, though less obviously, Rushdie and Marquez. It is not for nothing that the narrator of Eucalyptus (1999), Bail’s best novel, bemoans the ‘applied psychology’ that ‘has taken over storytelling, coating it and obscuring the core’. Yet, where the baroque outcroppings of detail in the magical realists of the 1980s serve to highlight the artifice of their creations, the detail of Bail’s fiction does quite the opposite, providing instead a framework for his fiction’s very particular reality.

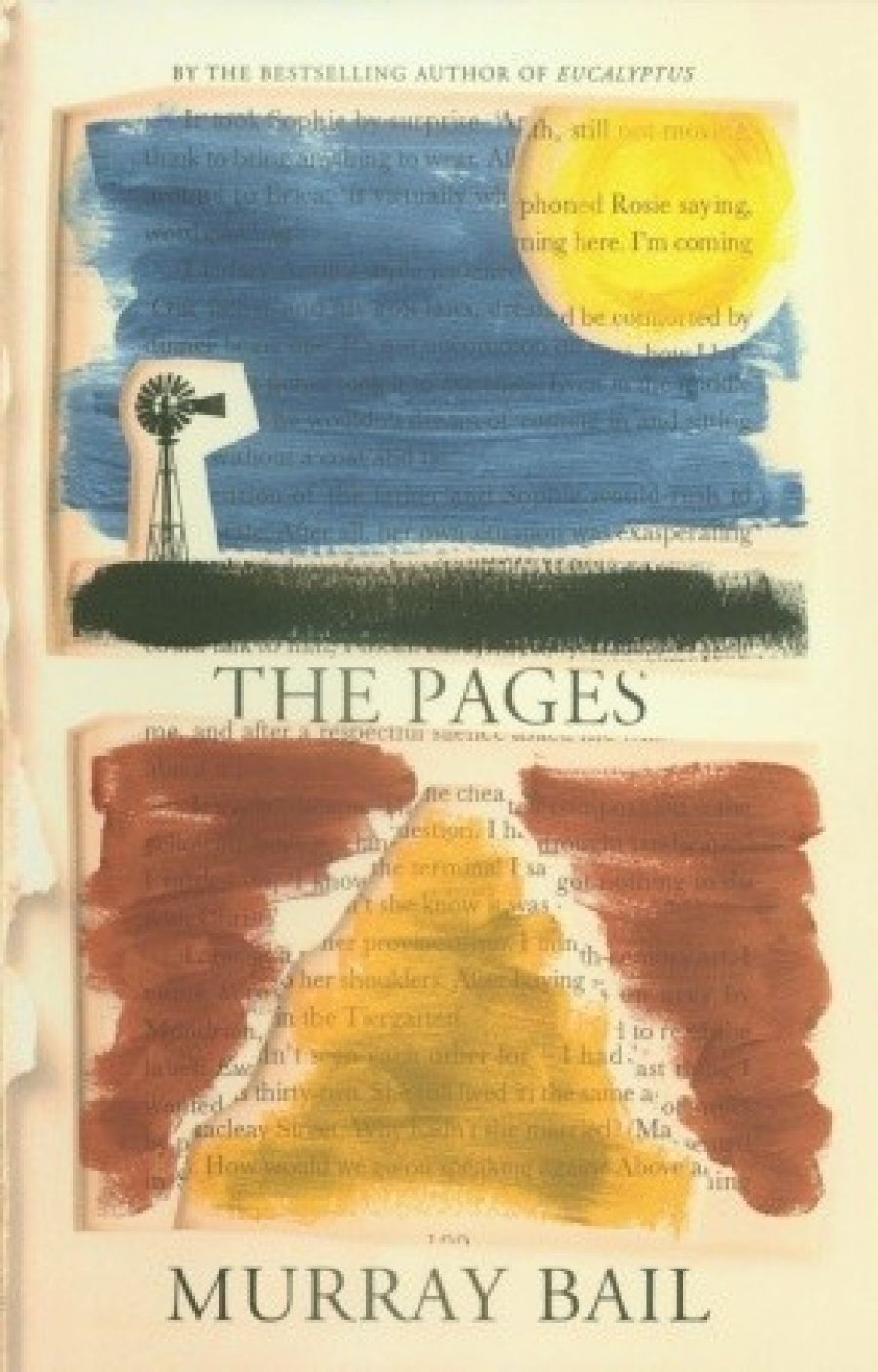

- Book 1 Title: The Pages

- Book 1 Biblio: Text, $34.95 hb, 224 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

In Eucalyptus, this curious literary double act was front and centre. In many ways the idea of telling a fairy tale through the classificatory language of botany might seem delightfully contradictory, and indeed much of Eucalyptus is built around the battle between these two ways of thinking and being. But the play and pleasure of the game which underpins Eucalyptus is emblematic of a deeper, almost Wittgensteinian concern in Bail’s fiction with the capacity of language to contain the world’s infinite multiplicity, and more particularly, the world’s indifference to our human need to classify and describe.

Perhaps appropriately, given its subject matter, Wittgenstein has a brief walk-on part in Bail’s new novel, The Pages: a passing pat on the head on a Cambridge lawn for one of the novel’s minor characters. Brief, but enough of a connection to the ‘real’ world of philosophy in the northern hemisphere to ‘excite envy’ in the cloistered world of Sydney University’s philosophy department.

Philosophy, or at least Bail’s somewhat idiosyncratic characterisation of it, lies at the heart of The Pages, which centres on a pair of quests for enlightenment. The first is that of Wesley Antill, the blueblood son of a wealthy pastoralist and racehorse owner (there is no doubt a thesis waiting to be written on the motif of racehorses, the lure of the track and the connections between the writing of Gerald Murnane, Murray Bail and Patrick White, in particular The Tree of Man). After refusing to follow in his father’s footsteps, Wesley embarks on a philosophical journey which will lead him first to Sydney, then to London, Amsterdam and Germany, and finally back to the family property, standing in the lonely, sun-bleached silence of western New South Wales.

The second is that of Erica Hazelhurst, the philosopher commissioned by the university in the days after Wesley’s death to travel to the Antill property and assess the merit of the legacy of this journey, the vast, unpublished, possibly unpublishable collection of manuscripts whose composition in a cowshed occupied the last years of Wesley’s life. Although we see little of the book itself, it’s difficult not to wonder whether Bail seeks to enjoin us in some wry commentary on the excerpts from his own commonplace books published as Notebooks 1970–2003 (2005).

Erica, who, as we are repeatedly informed, fears she is becoming a harsh woman, takes with her, almost on impulse, her friend, the flighty Sophie. Where Erica is a philosopher, Sophie is a therapist, their competing professions embodying one of the novel’s central dichotomies, that of philosophy and psychoanalysis, or, to be more precise, what Bail characterises (or caricatures) as the deep vision of one and the relentless solipsism of the other. Arriving at the homestead, Erica and Sophie meet Wesley’s surviving kin, his laconic brother Roger and the quietly bereaved Lindsey, who still dresses in velvet for dinner. Sophie flutters about, leaving Erica to begin the task of reading Wesley’s papers, and, though in a less organised fashion, to feel her way tentatively into some kind of understanding with Roger.

In this sense at least, The Pages is a romance, though it is, it must be said, a fairly cursory one. Despite two glowing scenes – one on a verandah, the other in a car – in which Erica and Roger relax into the possibility of love, for the most part their growing affection for each other takes place off-camera. Instead it is Wesley, and to a lesser degree the ‘restless, self-absorbed energy’ of Sophie, that dominate.

In a way, this is unsurprising. Though the story of Roger and Erica gives the novel its spine, its true concerns are elsewhere, focused not so much on human relationships but on deeper questions about the inevitability of loss and this inevitability’s connection to our need to find meaning in the world, to control it through language. Thus the novel seeks to distinguish two ways of understanding philosophy: the first as a system of thought, ‘an ambition to erect an intricate word-model of the world, an explanation, parallel to the world’; the other more like a process, or a way of being, a matter, to borrow from Montaigne, of learning how to die.

Perhaps predictably, given Bail’s fascination with the oppositions of north and south, Europe and Australia, old world and new, philosophy in The Pages is a pursuit from elsewhere, the creation of darker, colder places ‘with settled populations, where thoughts and sentences ... have the hidden urge to continue, to make an addition, a correction, to take an active part in the layering’. Here in Australia, it is a fragile exotic, broken by the fact of the land itself, its vastness, not just of space but of time. Or, as the philosopher John Bigelow put it recently, when seeking an explanation for the peculiarly realist and materialist bent of Australian academic philosophy: ‘Maybe in London or Paris it’s possible to think that there’s nothing outside the text. Yet on the beach at Bondi or in the baking sun back of Bourke, maybe it’s more obvious that the world has a structure that is not of our making.’

This is, of course, familiar territory for Bail, and he navigates it with his usual droll charm. There is a lot of engaging play with names and naming and ordering and classifying, from the young Wesley seeking to change his surname as part of the process of self-transformation that he thinks befits a philosopher, to Antill Senior’s fascination with philately. There is a delightful riff on Sydney’s aversion to philosophy. And there are the inevitable jokes about Adelaide. But for all that it is playful, it has its serious side. ‘Just about everything imagined is of no practical use,’ decides Wesley at one point, echoing W.H. Auden, but also anticipating the novel’s broader embrace of philosophy as a way of being, something necessary and indispensable.

At the same time, though, there is something oddly attenuated about The Pages. In part it is about the language. One of the pleasures of Bail’s fiction has always been the quickness and generosity of his prose, the moments of lightness and unexpected images that sustain its occasional improbabilities. These are still there in The Pages, but they are few: an encyclopedia with a broken spine, held together by ‘a ginger rubber band’; ‘The cold sharp air and the path alongside the rushing river’; a woman ‘with prominent sinews sweeping up from her shoulders like a Moreton Bay Fig, enough to stretch her credibility, for when activated, which was often, they gave a neurotic force to any ideas she may have had’. Yet it is also a sign of a more profound tension in the book, one between its concern with an inner truth given shape by the fact of mortality, and its playful form, a tension that it never seems able to resolve.

The Pages is not Bail’s finest novel by a long shot. Though it has its pleasures, too much of the book feels under-worked, even contrived. But even if it lacks the crafted elegance of Bail’s best work, there is, in its diversions, a capaciousness that belies its broader failings. In this sense at least, it makes its own case for the novel as the cultural form best equipped to answer Erica’s anxieties about her profession, its ‘rare disease of all-knowingness’, and the deeper need expressed in her plea as to ‘[w]hat possible dent could philosophy make on the fact of existence’.

Comments powered by CComment