- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Sport

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

The first words I ever read by Mike Brearley were in my first Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack, the 1976 edition: they were a tribute to his long-time teammate at Middlesex, wicketkeeper John Murray. The tone was warm, generous, and largely conventional, with a single shaft of ...

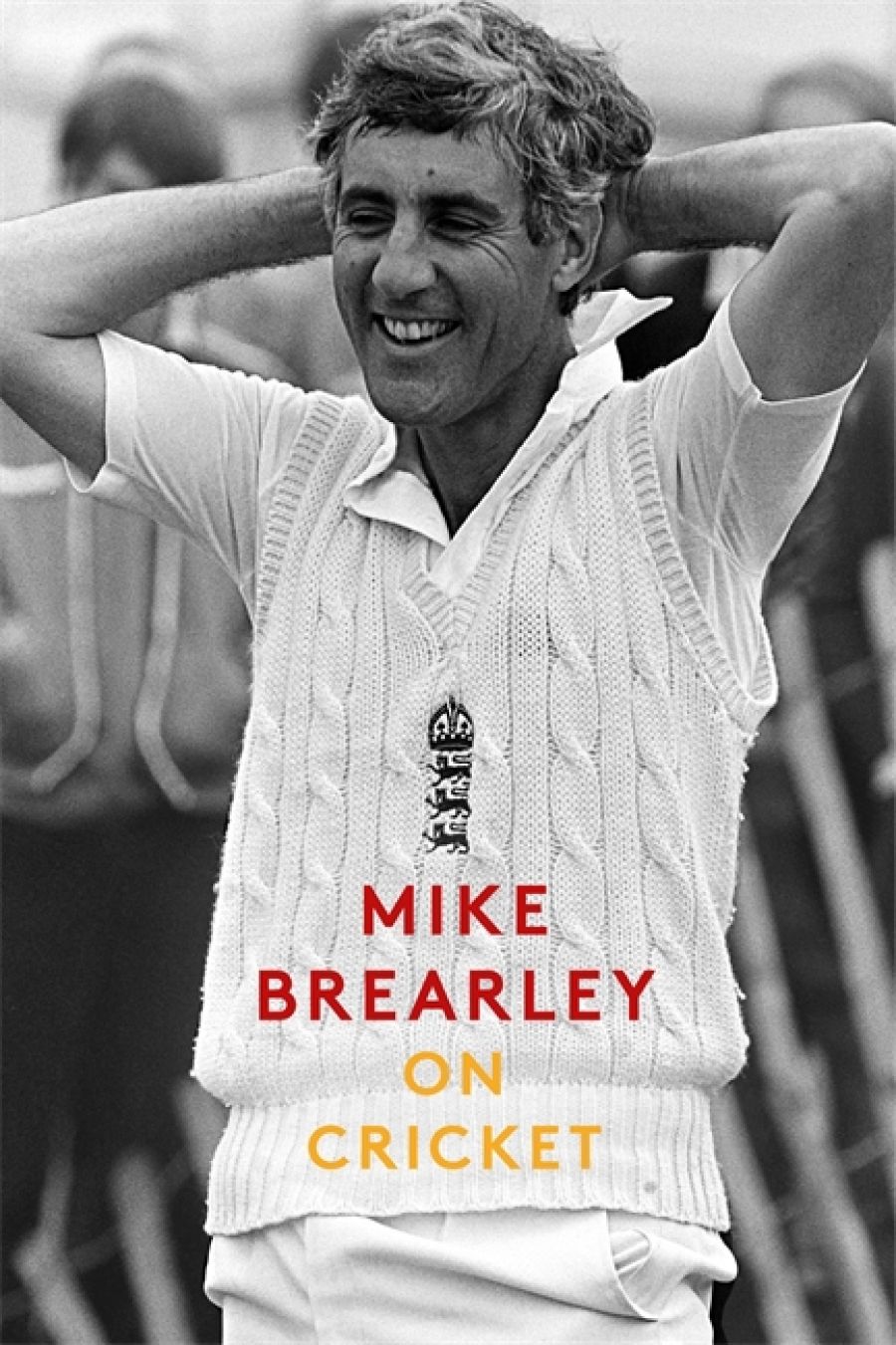

- Book 1 Title: On Cricket

- Book 1 Biblio: Constable, $49.95 hb, 418 pp, 9781472129475

Brearley is the author of three of the great contemporaneous accounts of Test series: The Return of the Ashes (1978), The Ashes Retained (1979), and Phoenix from the Ashes (1982). Since then, while holding down a day job as a psychoanalyst, he has continued to write cricket columns and essays, mainly for English Sunday newspapers, in addition to two further books: The Art of Captaincy (1985), a celebrated thesis, and On Form (2017), a meditation on the theme. To my taste, the last was at best a qualified success, too full of inchoate thoughts, too prone to this-is-true-except-obviously-for-all-the-times-it-isn’t dodgings about. Brearley on Cricket has a different unevenness, characteristic of collections. But when it is good it is outstanding, and worth lulls into the everyday.

In the first chapter, a memoir of his boyhood, he offers two thoroughly Brearley-esque sentences. Of his leg-spin-bowling father, he writes: ‘He had a high action, perhaps too high for a real leg-spinner.’ First the precision of the observation, then the hindsight analysis. Then: ‘He had a motorbike and sidecar, which seemed glamorous to me then, but rather precarious now.’ Looking, ever looking: it’s like Brearley is always going back to check his thinking and his feeling. His view on the spirit of cricket, for example, is of a piece, typically nuanced: ‘There is a risk of its being used to justify Establishment views, or one’s own views, wherever one is, when what is being advocated, often passionately, is the outcome of merely local conditioning. But it is not inevitable that it will be used in such a way.’

Nor is Brearley afraid to put himself to the test. In discussing last year’s ball-tampering fiasco in Cape Town, he harks back to a similar controversy during his own career in India in 1976–77, when the England team, of which he was vice-captain, was accused of applying Vaseline to the cricket ball from gauze bandages that bowlers were using to keep perspiration from their eyes. Were they? he wonders:

I have never known the answer to this question. Was I, am I, naïve? I was not involved in the discussions. But nor did I enquire too closely. Did I refrain from enquiry in case the truth might have been unpalatable? I am inclined to think the action was innocent; but certainly I should have made it my business to know …

Married to an Indian, Brearley writes well on the country and its cricket. Of that warmly remembered Indian team of the 1970s, with its four virtuoso spinners – Bedi, Chandrasekhar, Venkataraghavan, and Prasanna – he writes: ‘Especially on Indian pitches, this quartet was a formidable combination, and offered the captain something for every challenge. They were all, however, indifferent batsmen, so India often had a long tail. This was a feature of the old school of Indian cricket – with its reliance on sheer skill and subtly, and something of a scorn for utilitarian things like squeezing extra runs from the tail, or saving a few runs by athleticism in the field.’

The funniest piece in the book is dedicated to the Nawab of Pataudi Jr, the blue-blooded Indian captain with the look of a Fellini film star, who, when he took his only Test wicket, was granted the decision by an awestruck umpire: ‘That’s out, your highness.’ Brearley relates that Ian Chappell once tackled Pataudi about what he did with himself between cricket engagements, and grew frustrated when the Indian was so non-committal. ‘Ian,’ Pataudi said at last, ‘I’m a bloody prince.’

When he was the age I was when I first read him, Brearley received a report from his art teacher: ‘Fair, with flashes of brilliance.’ It pleased him – reports otherwise could be so mundane. His writing is better than that, but it is certainly true that his thoughts condense with a pleasing crack, straight from the middle of the bat: Tom Cartwright had integrity ‘like Caleb Garth’; Ian Botham ‘lacked prudence, meanness, calculation’; John Arlott ‘knew cricket more in the way of a lover than of a critic’; for Ian Chappell ‘squeezing out runs is a matter of almost moral significance, not to mention pragmatism’. Brearley is adept at conveying physical presence. Dennis Lillee, he perceives, is ‘so well proportioned that you didn’t realise until you came close that he was six feet tall’. There is a vivid vignette of Viv Richards in the commentary box, still magnetic even in repose: ‘He smiles, tells me how pleased he is to see me again, wishes me well. He has to do some work. He leaves the box. The box is the poorer for it.’ The same will be true when Mike Brearley clocks off from cricket grounds for the last time.

Comments powered by CComment