- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The first thing one notices about Jaclyn Moriarty’s Gravity Is the Thing is its narrative voice: distinctive, almost stylised. Exclamation marks, emphasised words in italics, a staccato rhythm, and clever comments in parentheses add up to a writing style sometimes deemed quirky ...

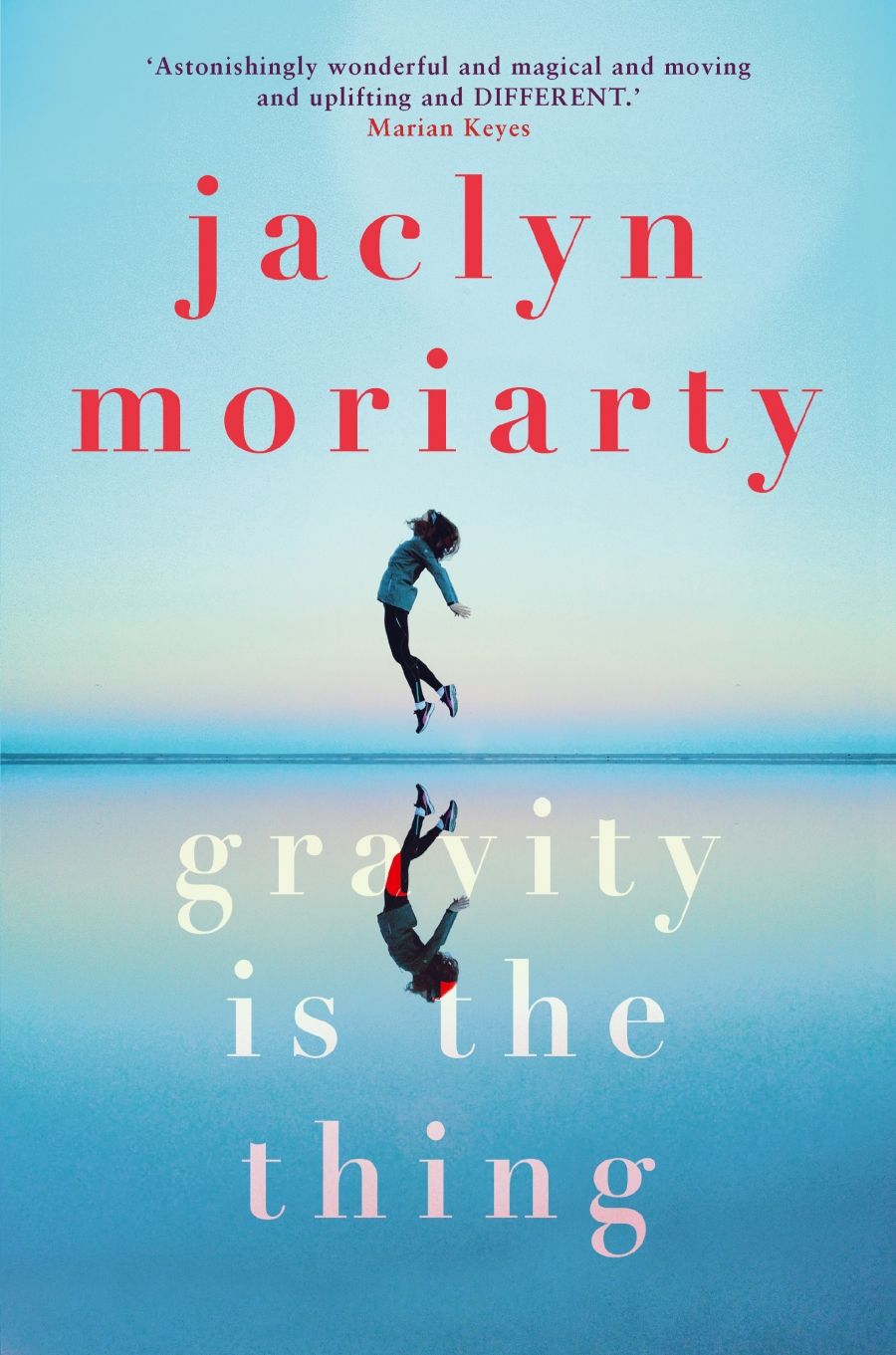

- Book 1 Title: Gravity Is The Thing

- Book 1 Biblio: Pan Macmillan, $32.99 pb, 472 pp, 9781760559502

Marketing aside, the distinction between ‘light’ and ‘heavy’ also presents as a theme within the novel. Gravity is The Thing contends that lightness does not necessarily mean frivolousness or superficiality, and that too much seriousness – or gravity – is its own kind of burden; the narrator reflects: ‘Heaviness is only lightness in disguise, overdressed.’

Themes of loss, grief, hope, the search for happiness, and the self-help industry are explored through narrator Abigail Sorensen, the thirty-five-year-old owner of the Happiness Café in Sydney’s Lower North Shore and single mother to four-year-old Oscar. Her life is shadowed by the absence of the men she has loved and lost, most notably her brother, Robert, who disappeared the night Abigail turned sixteen. That year she began to receive chapters from a self-help book called The Guidebook in the post. Twenty years on, she is now invited on an all-expenses-paid retreat to discover the truth behind The Guidebook.

The events propel Abigail on an often comical search for meaning in the world of self-help, which she describes as:

a vast and thriving industry. It spans books, movements, religions, communes, therapies, diet, psychics, philosophies, life-changing novels and exercise regimes. From the earliest civilisations, people have been trying to sort out how to live, the point of it all, the key to happiness, and how to interact in a way that makes everybody like us.

Abigail turns to books like The Celestine Prophecy and The Secret (‘I did not believe a word of that book, but I wanted to so badly that I played as if I did’), ancient philosophy (‘Socrates strikes me as insufferable’), and feng shui (‘It occurred to me that chi might share some characteristics with the universe: all-knowing, all-wise, all-magical, yet also a bit daft’). Moriarty pokes fun at the absurdity and contradiction of purported rules to life and juxtaposes them with the confusing realities of living. Her parenting experiences are especially well rendered: although Abigail constantly questions how to live, she is living just the same, contending with daily parenting dilemmas, picking up toys, and slicing up carrot sticks while she contemplates the complexities of happiness (‘You think you’ve got life figured out, you lean back on the couch – and then it hits. You don’t have superpowers. You haven’t even got basic grammar’).

Jaclyn Moriarty (photograph by Wendy McDougall)

Jaclyn Moriarty (photograph by Wendy McDougall)

Ambivalence permeates Abigail’s narration. Even when she is emphatic, it is often unclear if her statements are meant earnestly, flippantly, self-accusingly, exasperatedly. This can frustrate the reader, who wonders: ‘What are you trying to say here?’ Abigail is aware of the ambiguity; indeed it is part of the point. Her sympathy for another character is insightfully expressed as ‘a profound yet paper-thin (mismatched adjectives, I realise, and yet ...) sadness’. But this inability to choose where to settle – profound or paper-thin? – at times fills the reader with a nihilistic sense that, to Abigail, everything matters and nothing matters.

The novel is divided into seventeen parts, each subdivided into chapters. Moriarty manages the leaps in time seamlessly, and though the first half of this long book could be pacier, the plot remains engaging. Propelling the narrative forward are the question of Robert’s disappearance, the mystery of The Guidebook and Abigail’s fellow participants, as well as curiosity about the fate of Abigail’s romantic relationships. While the premise of The Guidebook fails to convince (a fifteen-year-old receives mailed advice from two adult strangers and replies with reflections on her sex life), as the novel progresses the story becomes increasingly absorbing, and by its conclusion the reader is invested.

Moriarty shines in the novel’s excellent final third, where the writing becomes intuitive, fluid, resonant. Dream sequences and allegorical references to flight are incorporated into thoughtful chapters that vary in length and subject. When the groundwork is thus laid, even a four-word chapter becomes deeply moving. The story gives way to vulnerability and revelation in a satisfying, beautifully written ending.

Despite some tonal inconsistency, this immensely readable novel will appeal to a broad readership for its humour, candour, and moments of heartfelt recognition. While readers allergic to exclamation marks are advised to stay away, in the right hands this book will become a treasured favourite.

Comments powered by CComment