- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Siri Hustvedt’s latest novel, Memories of the Future, weaves together three distinct threads. The overarching narrative, set in the recent past, unfolds contemporaneously with the book’s composition. It consists of the reflections of a writer with the mysterious initials SH ...

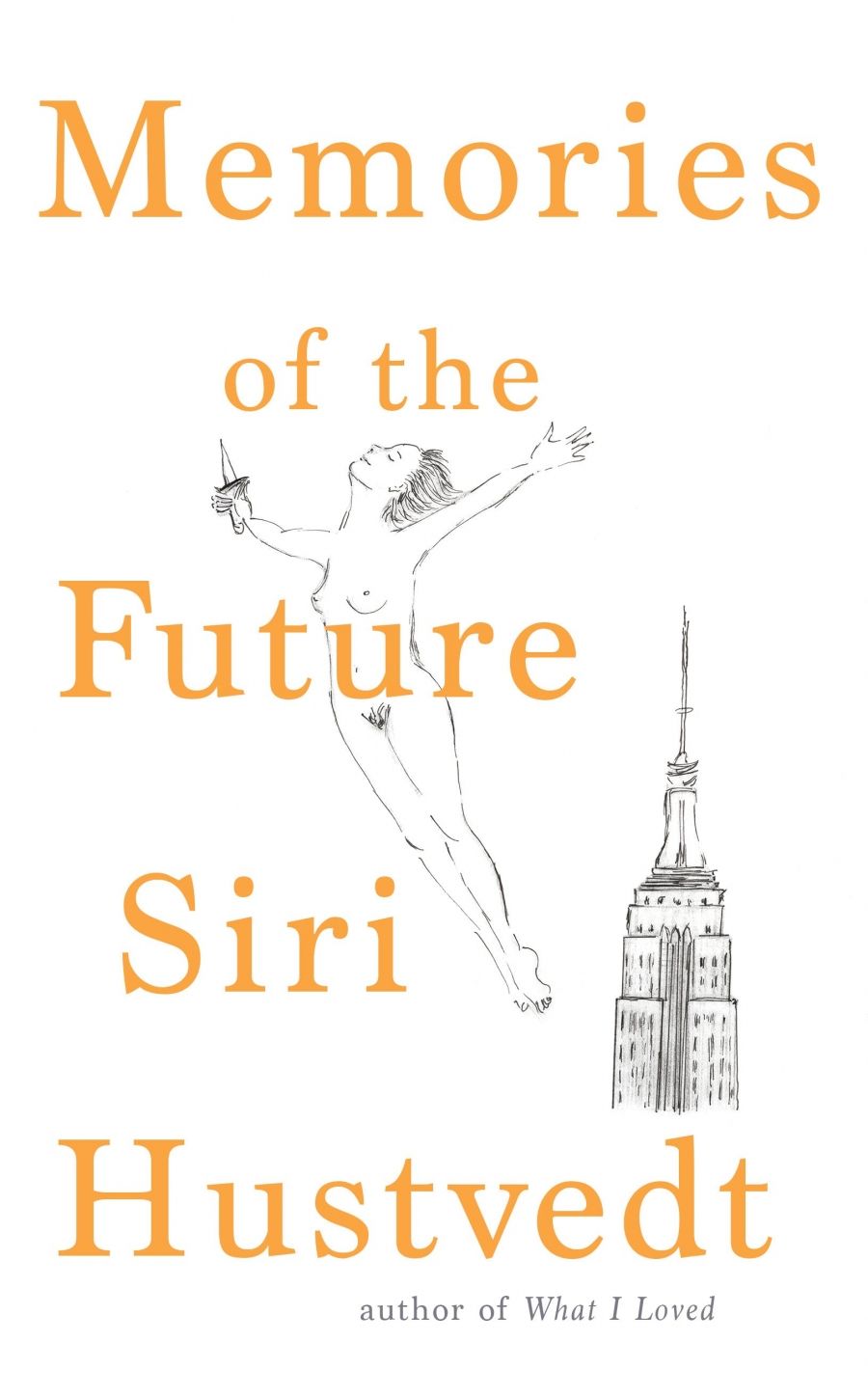

- Book 1 Title: Memories of the Future

- Book 1 Biblio: Sceptre, $32.99 pb, 318 pp, 9781473694422

Memories of the Future is also a timely work. It is a novel that addresses contemporary gender politics, and which might be read as Hustvedt’s refracted contribution to the #MeToo movement. The young SH, a lanky blonde with striking Nordic features, tends to attract a certain amount of attention from members of the opposite sex. She allows herself a few erotic adventures, but her negative experiences accumulate and eventually come to predominate. She is ogled, patronised, and abused by a complete stranger as she is walking down the street. The air of menace comes to a head about halfway through the novel when she narrowly avoids being raped at the conclusion of a date with an arrogant creep, who barges into her apartment and throws her against a bookshelf.

Siri Hustvedt (photograph by Marion Ettlinger)

Siri Hustvedt (photograph by Marion Ettlinger)

These individual experiences are presented as elements of an encompassing social critique. Memories of the Future is a novel that describes a young woman’s political awakening, her dawning awareness of the underlying pattern. It is saturated with examples of entitled and reprehensible male behaviour, which it presents as evidence of a smothering patriarchal culture. The novel’s central intrigue concerns the young SH’s neighbour Lucy Brite (Hustvedt has a fondness for a kind of low-wattage Dickensianism when it comes to naming her characters). When SH hears Lucy through the thin walls of her apartment repeating the phrase ‘I’m sad’ and conducting disturbing conversations with herself in different voices, she starts to piece together the story of the unhappy past that has left Lucy estranged from her son, grieving for a daughter who died when she either fell or jumped or was pushed from a window, and filled with bitterness toward her abusive and controlling ex-husband, who liked to discipline his family by locking away their possessions. The latter detail prompts SH to ask one of the novel’s defining questions: why should he be the one with the key?

For the young SH, this kind of patriarchal oppression comes to be associated with her desire to be admitted into the hallowed realms of art and intellect. Memories of the Future supplies an emblematic example of gendered cultural effacement via SH’s interest in Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, a largely forgotten poet and avant-garde artist, who is more than likely to have been the real creator of Duchamp’s famous ‘Fountain’. The sense of exclusion also inspires the novel’s best set-piece: a boozy dinner party that culminates in a male philosophy professor delivering a condescending lecture to the female guests about the problem of other minds. Riled by the professor’s overbearing behaviour towards his wife and his assumption of their ignorance, SH launches into a blistering rebuttal of his outdated Cartesian assumptions, working herself into a state of lucid fury that culminates in her quoting Wittgenstein in German and then passing out.

Though it is a pointed work in this sense, Memories of the Future is a novel and not a tract. It is a writerly book in the best sense, not simply by virtue of its ritual acknowledgment of modernist masters (Baudelaire, Hamsun, Kafka) and its studiously layered narrative, but because of its essential element of formal self-awareness. Hustvedt repeatedly breaches the fourth wall, drawing attention to the acts of writing and reading, noting their separation in time and space, and their ability to collapse that distance. She sees meaning and understanding as complex issues that must take account of cultural authority, the wilfully distorting nature of our powers of recollection, and the logic of competing genres. In Memories of the Future, she plays different genres against one another to create a distinctive hybrid that manages to be many things at once: a philosophical meditation, a fictionalised memoir (a tautology according to Hustvedt, who quite rightly insists that all memoirs are untrustworthy), a nostalgic evocation of pre-gentrification New York, a repudiation of the mechanical logic of detective fiction, a declaration of artistic integrity, and a withering cultural critique. But perhaps its most charming feature is its element of homage to the Romantic idealism of Hustvedt’s ‘female Quixote’, the young SH, who at the end of the novel literally rises above it all.

Comments powered by CComment