- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

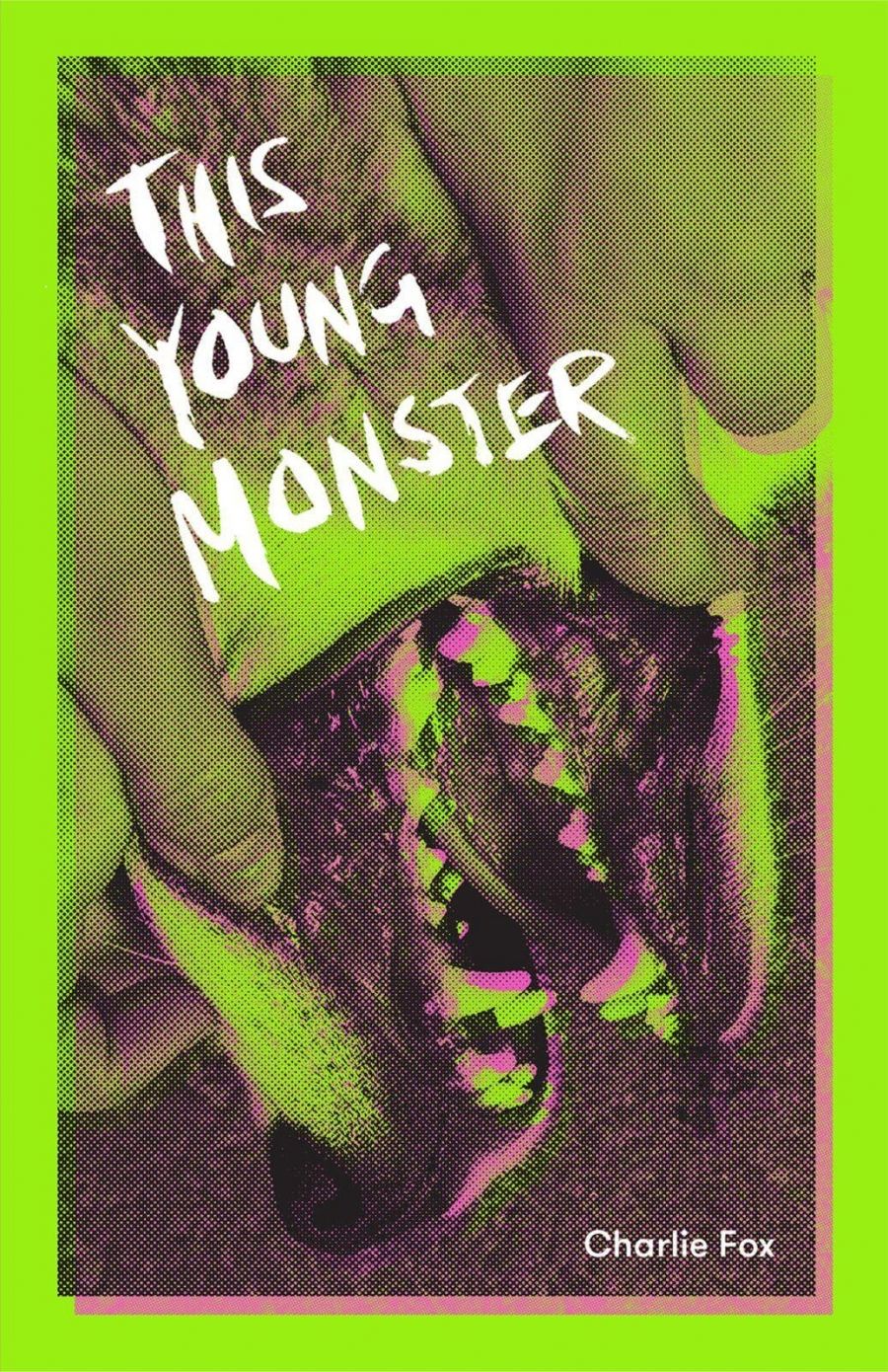

In his début collection of essays, This Young Monster, Charlie Fox pays homage to a range of artistic icons (or ‘monsters’) who revel in freakish and reckless play. His creatures of choice include filmmakers Buster Keaton and Rainer Werner Fassbinder, photographers Diane Arbus and Larry Clark ...

- Book 1 Title: This Young Monster

- Book 1 Biblio: Brow Books, $29.99 pb, 256 pp, 9781925704143

Ditto the book’s centrepiece, ‘Transformer’, where Fox becomes Lewis Carroll’s Alice. With what only amounts to a slight shift in expression and tone from the personally attributed essays, the precocious and adventurous Alice plays the grande dame, theatrically self-canonising and springing willy-nilly across her own heritage in twentieth-century art. She lands upon works in which her observable legacies of metamorphosis and skilful self-evasion have received little critical attention – for example, the portrait-photographs of Francesca Woodman, Claude Cahun, and Cindy Sherman. Hitting ‘reality’ with a thump, she brilliantly recognises herself in the misbegotten and rebellious girl (played by Linda Manz) in Dennis Hopper’s 1980 treasure Out of the Blue. Here, ‘Wonderland’ has turned to wasteland: the girl is left to navigate only a dreary world, one coming down from the starry-eyed visions of the psychedelic 1960s with which Alice has been more commonly associated.

The likening of Alice in Wonderland to the austere Out of the Blue epitomises Fox’s agility as a cultural critic. In pieces dedicated to individual subjects, he frequently deflects to a wide range of seemingly disparate works. Making correlations, he allows his essays to detour and ‘go roaming’ and meanwhile agitates the critical reputations of the works under discussion. (Such deviations offer us a sketch of his own charming idiosyncrasies as a compiler and consumer.) In his Alice’s surprising invocation of Out of the Blue, the ghosts of other possible lives, hovering above both Carroll’s and Hopper’s works, become more perceptible than before.

A still from Gummo (1997), directed by Harmony Korine

A still from Gummo (1997), directed by Harmony Korine

Discussions of Harmony Korine’s film Gummo (1997) and the photographs of Arbus and Clark give further evidence of that energising critical faculty. Since it opened to an incensed and dismissive public, Gummo has long been defended as a work invested in raw realism, bucking against American cinema’s established traditions of escapism and idealism. Its brutality (and dark hilarity) still intact, Fox instead accesses the film and all the magical features that saturate it by way of the proto-Hollywood Alice in Wonderland and the prototypical Hollywood The Wizard of Oz (1939). (He shares with experimental filmmaker and Tinseltown gossip Kenneth Anger an underground sensibility with a ‘Hollywoodian reflex’ – it feeds and enriches itself on Hollywood pulp; its dishonoured grunginess still wants a share in all the sparkly glamour.) Similarly, for Fox the stark representation of hidden realities in the photographs of Arbus and Clark do not preclude their phantasmagorical and performative elements. These artists use reality as yet another ‘luscious material supplied by the earth’, something to be appropriated and remoulded if not fiercely combated.

Perhaps the best example of this need to modify and recreate – to treat body and earth as canvas and clay – is the Melbourne-born fashion icon Leigh Bowery, the subject of one of the book’s best essays. ‘His whole persona was a mask,’ said his wife, Nicola. Their marriage was also a mask, and veils abide even in Lucian Freud’s series of portraits of the corpulent Bowery in the nude, performing a private life. Here again, Fox leaves his subject even larger than we found him: the artist becomes an explosive gateway drug, goading him to sift through ideas about ‘queer monstrosity’ via Oscar Wilde, Anne Carson, the rapturous designs of Alexander McQueen, and even film director Todd Haynes’ homage to Jean Genet, Poison (1991). (The accursed angel Genet otherwise lingers as a mostly unspoken presence throughout the book.)

In that chapter, Fox’s prose is incisive and analytical but glimmers still with the eccentricity and absurdity that he so cherishes in his subjects. It is in only occasional moments of self-reflection and self-justification – for example, when he reckons with the contemporary social and political significance of monstrosity in the final chapter (otherwise dedicated to the book’s ‘mascot’, Rimbaud) – that his writing loses some of its electric charge. Fox is most potent when he is play-acting, thinking leapingly, and keeping his subjects’ ‘grand imaginative follies’ afloat, as he is for so much of this exiciting book.

Comments powered by CComment