- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Theatre

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

People who were university students at a particular time often like to regard those years as exceptional, a perspective which, embellished by nostalgia, memoirs, and media hype, can take on mythic proportions. A case in point is the concurrence of people and talent that led to a high point in student theatre ...

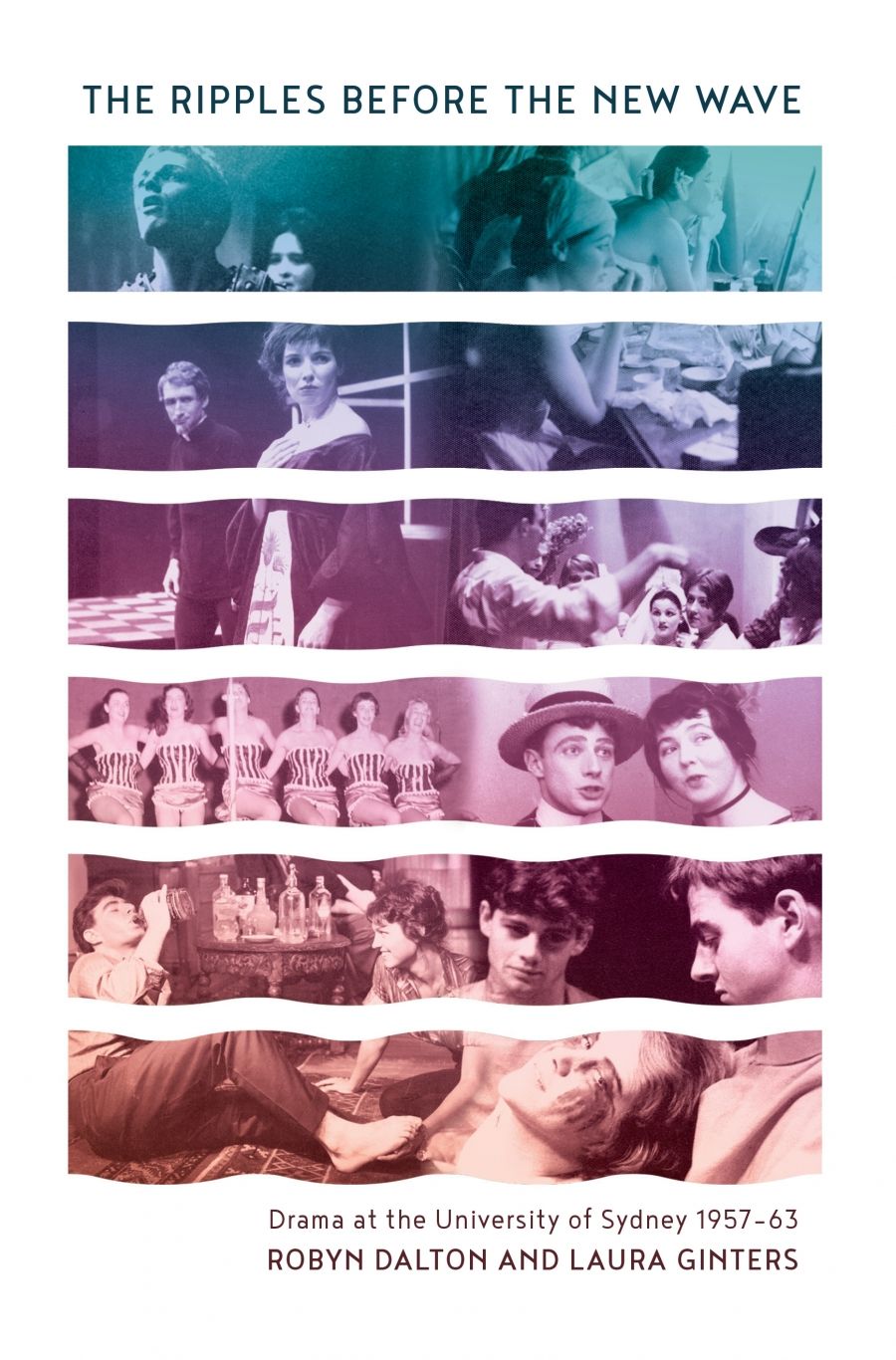

- Book 1 Title: The Ripples Before the New Wave

- Book 1 Subtitle: Drama at the University Of Sydney 1957–1963

- Book 1 Biblio: Currency Press, $40 pb, 246 pp, 9781760622589

But the Sydney Uni upsurge was not an isolated development. Student drama had a long and honourable tradition at the university. The work of playwrights like Lawler, Richard Beynon, and Peter Kenna foreshadowed what was to come. Exciting independent theatre was to follow with the APG in Melbourne and Jane Street in Sydney. Nevertheless, at a distance of sixty years, an assessment of the era and its importance is timely. Three people emerge as highly influential.

Pamela Threthowan, a versatile English actress and director, energised student theatre with more than twenty productions in five years, including some of the first Beckett plays to be presented in Australia. Leo Schofield, later festival director and arts entrepreneur, initially contributed design skills and proceeded to direct revue, Restoration drama, Brecht, Purcell, and the ever-popular Victoriana. Ken Horler was a genius at spotting talent and an adventurous director of work by Brecht, Goldoni, and e.e. cummings. Horler later established Sydney’s Nimrod Theatre (1970) and, with Bell and Wherrett, introduced new Australian work and offered fresh, appealing treatments of the classics.

Robust competition between rival dramatic societies – SUDS (the venerable SU Drama Society, established in 1889) and the newer Players – along with work by the colleges, language faculties, music, and other specialist societies, generated diverse and vibrant student performances. Into a theatre environment dominated by the tired imports of commercial producers, the societies brought the work of contemporary playwrights like Pinter, Brecht, and Beckett, attracting audiences from outside the university and even reviewers from the mainstream press. Paradoxically, there was ‘an almost total absence of Australian plays’ among the ripples.

Ron Blair, Stefan Gryff, Ken Horler (corpse), and John Bell in 'Tis Pity She's a Whore (photograph by Joe Vissell)

Ron Blair, Stefan Gryff, Ken Horler (corpse), and John Bell in 'Tis Pity She's a Whore (photograph by Joe Vissell)

With no formal training available (NIDA took in its first students only in 1959), university drama offered an opening. Among the outstanding acting talents of the period were nineteen-year-old John Bell, who performed a Malvolio of astonishing depth and maturity, directed by Horler; and Arthur Dignam, who gave intense and moving performances in works like Pinter’s The Birthday Party, but ‘lacked the drive and self-confidence that propelled [Bell] into his subsequent highly successful career’. Another success, Philip Hedley, decamped early for a distinguished career at London’s Stratford East.

In those pre-feminist times, it was men who filled the key creative roles. Clive James, ‘Chester’ (Philip Graham) and John (later Kate) Cummings dominated sketch writing for the popular satirical revues. Casting of women often depended more on physical attributes than perceived talent. Albie Thoms (later director of absurdist theatre and avant-garde film) found the orientation week SUDS team ‘too intimidating’ to join, a reaction many young women would have shared. Nevertheless, gutsy women like Greer, Colleen Chesterman, and Rosaleen Smyth gamely auditioned.

The freshers who launched into the new era of student theatre were very young, some barely sixteen. As beneficiaries of Commonwealth scholarships and children of the Menzies area, most of us were shamefully apolitical and extremely naïve. Ignorance about homosexuality was widespread, and almost no one was openly gay. Study was secondary to fun until performances were suspended, giving way to serious cramming for the looming exams.

By the mid-1960s the great flush of student drama was over. Many participants joined the then-customary exodus to London, or dispersed into related areas or dropped out of theatre altogether.

Dalton and Ginters painstakingly researched The Ripples over a number of years. They record all productions, directors, and originating organisations between 1957 and 1963, with detailed accounts of more notable productions, providing more than enough evidence for their evaluation of the era’s importance. Their in-depth interviews with participants yield lively anecdotal material, enhanced by rare archival photographs. There is a comprehensive index.

It’s a nostalgia fest for anyone who was there, but there is much for anyone interested in Australian theatre history. Golden age or not, what is unarguable is that for most of us, to be young (and there) was very heaven.

Comments powered by CComment