- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Almost all historical events are attended by myths, some of them remarkably persistent, but Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War has perhaps more than its fair share. Mark Dapin has set out to dispel what he sees as six of these myths, which he first encountered working on his book The Nashos’ War ...

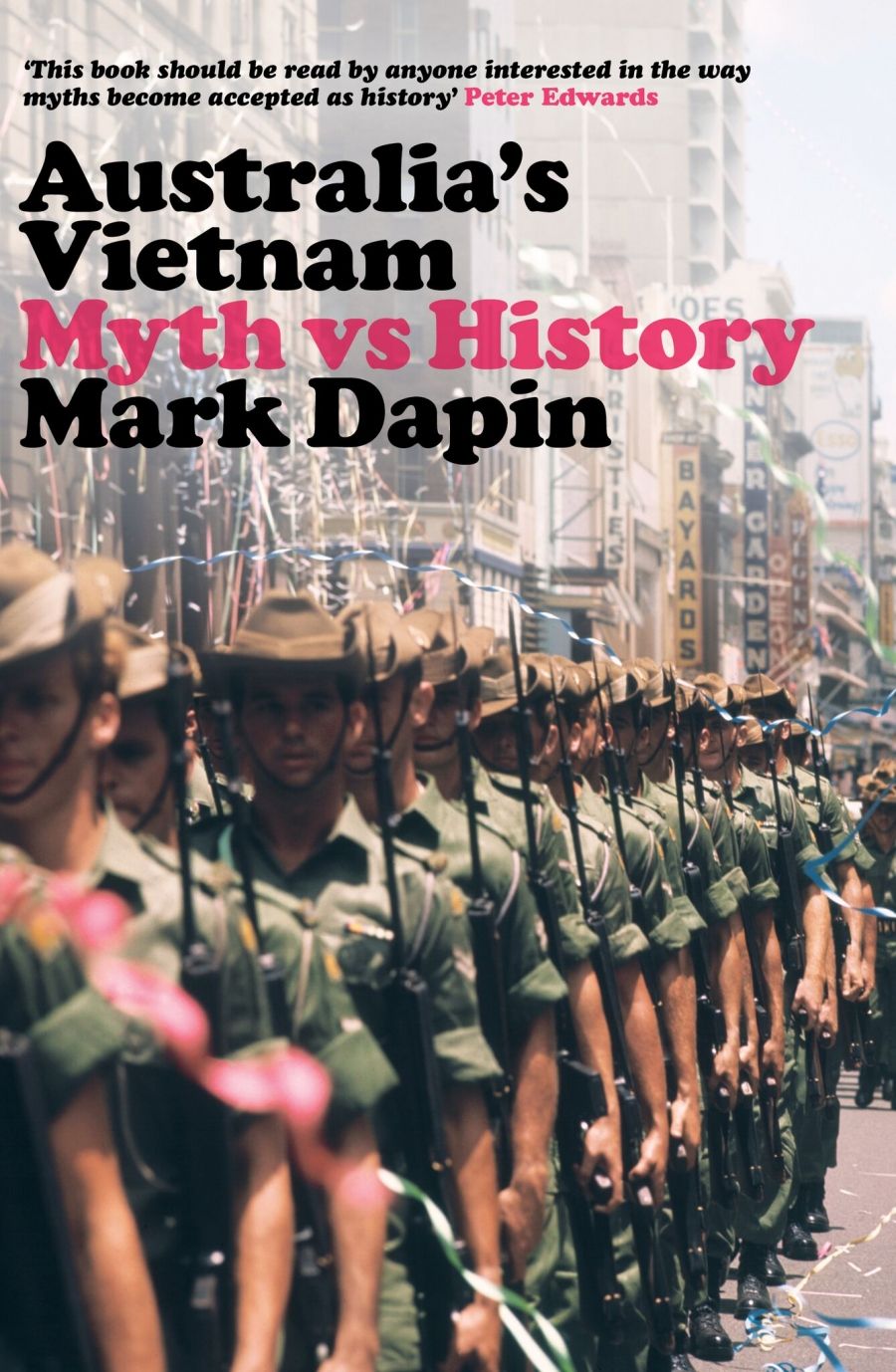

- Book 1 Title: Australia's Vietnam: Myth vs history

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $32.99 pb, 261 pp, 9781742236360

Dapin’s second myth is that the ballot under which some birth dates were drawn was in some way fixed to obtain, for example, persons with particular occupations. I doubt that this was ever generally believed, but the book is interesting about the kinds of groups who became national servicemen. One reason that they do not seem to have reflected a cross-section of the community is that the scheme only lasted for eight years, and deferments for full-time study meant that, at least in the early years, there would have been few university graduates, though it must be remembered that, in comparison with today, only a small number of persons attended university in Australia.

The third myth is that there were no parades for returning soldiers as there had been in earlier wars. The book notes that, for logistic reasons, there were few homecoming parades in 1918 and 1945. In contrast, there were welcoming crowds of several hundred thousand in Sydney every year for troops returning from Vietnam between 1966 and 1969. This myth seems to have arisen from a feeling on the part of some of the troops that their role in Vietnam was not properly recognised on their return. This may be closer to the truth, given the fact that after the fall of Saigon in 1975 it was obvious that the allied forces had lost the war. Arguably, however, because this was the first conflict Australia had been involved in that did not have the support of the great bulk of the community, it was clear from the outset that this would be different from earlier wars and that those returning would never be viewed as heroes like their predecessors.

Somewhat allied to the notion of no homecoming parades are the fourth and fifth myths: that returning troops were met by protests when they arrived at airports in Australia; and that they were the subject of abuse and, in some cases, physical attack once back in Australia. Dapin examines all the accounts of these allegations and concludes, correctly in my view, that, except for one isolated incident, there was no evidence for any of them. In relation to airport protests, for example, he notes the absence in ASIO records of any reference to them, despite this being a time when ASIO operatives attended and recorded almost all protests against the war. On the question of public abuse of returned soldiers, it is certainly my recollection from the time that this did not occur. One reason why it didn’t was that those groups who were opposed to the war did not see Australia’s role in Vietnam as the responsibility of army personnel but of the national government that had sent them there.

Members of 5 Platoon, B Company, 7th Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (7RAR), just north of the village of Lang Phuoc Hai, beside Route 44 leading to Dat Do. United States Army Iroquois helicopters are landing to take them back to Nui Dat after completion of Operation Ulmarra, the cordon-and-search by 7RAR of the coastal village of Lang Phuoc Hai. (photograph by Michael Coleridge/Australian War Memorial)

Members of 5 Platoon, B Company, 7th Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (7RAR), just north of the village of Lang Phuoc Hai, beside Route 44 leading to Dat Do. United States Army Iroquois helicopters are landing to take them back to Nui Dat after completion of Operation Ulmarra, the cordon-and-search by 7RAR of the coastal village of Lang Phuoc Hai. (photograph by Michael Coleridge/Australian War Memorial)

The final myth is that of war crimes committed by Australians in Vietnam. Despite some anecdotal accounts, Dapin was unable to find any hard evidence for this, although doubtless there were many untargeted civilians who suffered or perished because of their proximity to military engagements by all parties.

It is not put forward as one of Dapin’s myths, but there does seem to be an assumption in some later accounts of the Vietnam period that the war was always unpopular in the Australian community. It is true that the conflict did not have the whole-hearted support of earlier wars, but the Liberals, under the leadership of Harold Holt following Robert Menzies’ retirement in January 1966, won what was then the largest election victory in Australian political history ten months later. The war was one of the foremost issues in the poll because of Labor’s opposition to the troop commitment that had been made in 1965. As the book points out, a Gallup poll in December 1968 still showed forty-nine per cent of respondents believed that Australia should stay in Vietnam and thirty-seven per cent that its troops should be withdrawn. This was at a time when it might be thought that it had become obvious that the war could not be won, and when the debate in the United States on its continuation had become widespread. This was not the Australian electorate’s finest hour. The majority of the community was prepared to allow a small group, chosen by lot, to risk their lives in a conflict that had no impact on anyone else in that community. It was selfish and irresponsible behaviour that still leaves a bad taste fifty years later.

It might be assumed from some other accounts of this period that universities at least were oases of radicalism and so did not reflect the rest of the community. In fact only a very small minority of university students had any real interest in politics, and only some of those were actively opposed to the war. In something of a contrast to many of their counterparts in the United States, Australian universities at the time did largely reflect the views of society as a whole.

One early myth that may have been, partially at least, dispelled by later histories is that the Australian government was pressured by Washington to make its first significant commitment of ground troops in April 1965. The exchanges between Canberra and Washington indicate, however, that the Australians, particularly Foreign Minister Paul Hasluck, effectively solicited the invitation from the Americans to become involved in the conflict at a serious level. Moreover, in early 1965 they urged Washington to step up the war at a time when there was still some debate in the US administration as to what was the best course to take in Vietnam.

This book is a valuable contribution to the history of Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War. It will, however, bring little comfort to the Australian soldiers who fought in this misguided and misjudged conflict.

Comments powered by CComment