- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

In July 1924, a Tasmanian senator from the conservative Nationalist Party, Herbert Payne, introduced a bill to bring about compulsory voting in Australian national elections. His proposal aroused little discussion. Debate in both the Senate and the House of Representatives – where another forgotten politician ...

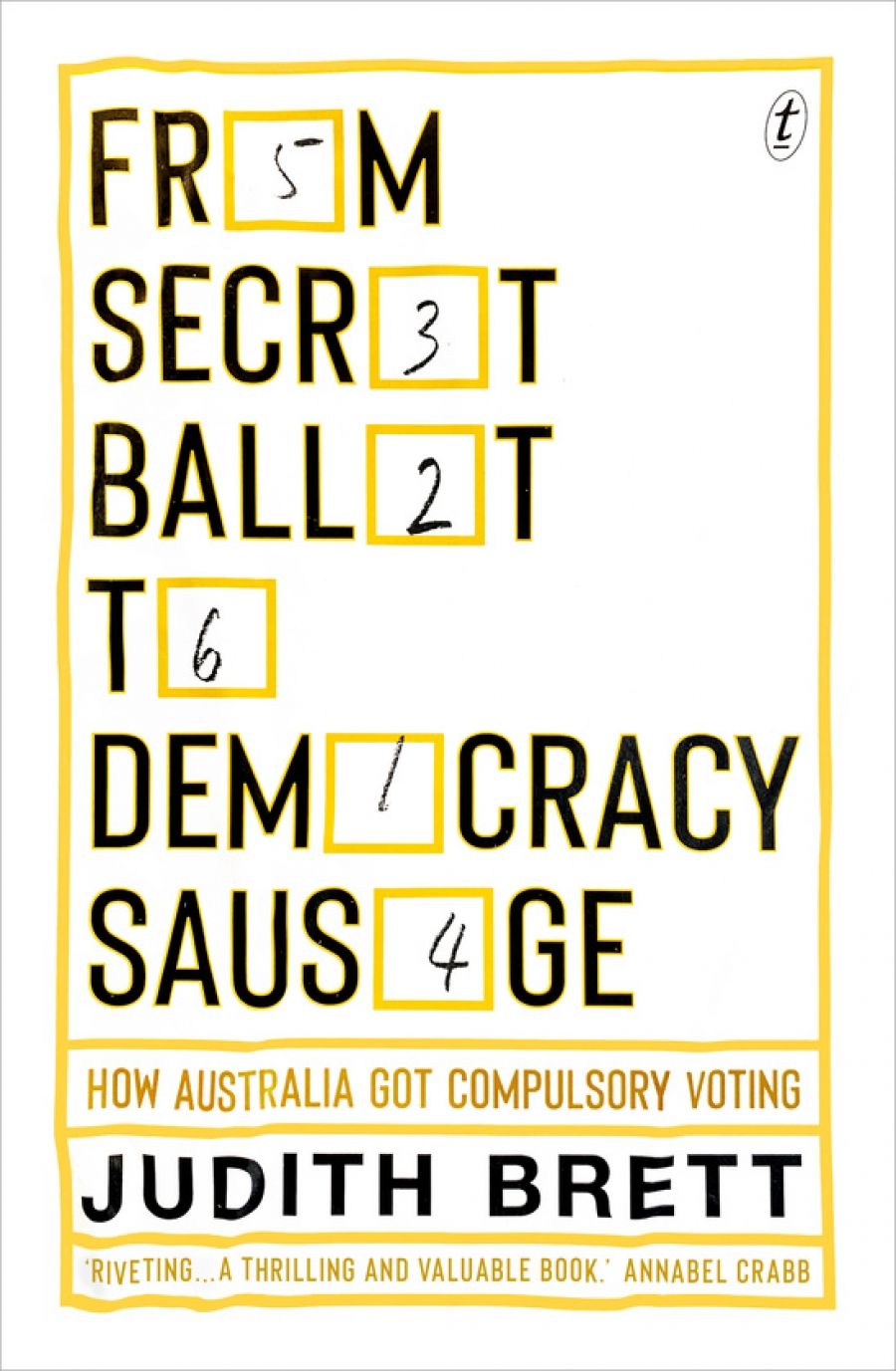

- Book 1 Title: From Secret Ballot to Democracy Sausage: How Australia got compulsory voting

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $29.99 pb, 199 pp, 9781925603842

Brett’s argument is that compulsory voting was so uncontroversial because its way had been paved by decades of colonial history. Australia had developed a political culture in which rights were seen to have been bestowed by government rather than residing naturally in individuals or emerging out of a contract between state and citizen. Here, Brett relies on the understanding of Australia as a Benthamite society, the subject of an influential 1985 essay by Hugh Collins. If the role of the state was to produce the greatest good for the greatest number, electoral systems needed to be devised to ensure the voice of the majority was faithfully reflected in results.

This sensibility gave rise to two distinctive and unusual electoral practices. One, the ostensible subject of this book, is compulsory voting. The other is the ‘Alternative Vote’ – called preferential voting in Australia – used in House of Representatives elections since 1918. Brett suggests that both need to be seen as products of Australia’s majoritarian political culture. Compulsory voting means that the views of a majority of eligible voters, not merely those who show up, are registered at the polls. Preferential voting ensures that where there are more than two candidates, no one wins with a minority of votes – as occurs under a first-past-the-post system – unless they are also able to gather sufficient preferences from those who have their primary vote to other candidates.

There had been advocates of compulsory voting since the nineteenth century. Some believed it would favour conservative over progressive parties because it would bring out of the woodwork the apathetic and satisfied who would otherwise fail to vote at all. Labor initiated compulsory federal registration in 1911, which Brett believes made compulsory voting inevitable. And when Queensland introduced compulsory voting in 1915, followed by a large swing to the Labor Party that saw it win office, Labor politicians had no obvious reason to stand in the way. Poor voter turnout in the early 1920s helped secure the case for compulsion.

The story of preferential voting is equally fascinating. The rise of Labor was a barrier to its implementation because that party did so well under the first-past-the-post system that operated until 1918. Labor candidates had frequently won seats because the non-Labor parties split the vote. Billy Hughes introduced preferential voting in 1918 precisely to prevent the continuation of this problem, in the context of the rise of the Country Party. A fat lot of good it did him personally: an empowered Country Party under Earle Page got rid of him as prime minister after the 1922 election.

Former Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes (photograph via Australian Prime Ministers)

Former Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes (photograph via Australian Prime Ministers)

Brett shows that these electoral innovations were not isolated experiments. From the earliest years of self-government, the colonies had been prepared to make major departures from old-world practice. But contrary to the impression that they were the first in the world to use the secret ballot, the key colonial innovation was to ensure that the ballot to be filled out was provided by the government. More generally, Australians have been most comfortable with giving independent public servants the job of running elections, a stark difference from America’s continuing record of partisan manipulation. And from Federation onward, there were strong impulses toward national uniformity, another contrast with the United States and its kaleidoscopic voting arrangements giving ample scope for manipulation and disenfranchisement.

In Australia, we like to provide fulsome opportunities to vote, and a vast and relatively efficient bureaucracy has grown up around ensuring fair and inclusive ballots. Practices now taken for granted – such as Saturday voting, a national roll, and postal, absentee, overseas, and pre-poll voting – are the products of decisions made about how to conduct elections. Probably only New Zealand rivals Australia in the ease with which one can exercise the franchise. Interestingly, these two countries were also among the earliest to allow women to vote, while Australia also allowed them to stand for parliament from 1902 (South Australia permitted both women’s voting and candidature from 1894).

The story is not one of unqualified achievement. Australia made it harder for Indigenous people to vote after 1901; that is, when it did not prohibit them from doing so entirely, as occurred in some states. Brett nonetheless shows that there were liberals in the early federal parliament who were prepared to follow the logic of their own convictions by advocating votes for Aboriginal people. The racists, however, won the day, and liberals such as Richard O’Connor did not feel strongly enough about protecting the democratic rights of ‘a dying race’ to risk rejection of their electoral bill.

Brett’s enthusiasm for Australia’s electoral achievements requires her to avert her eyes from some aspects of state politics. The gross malapportionment of lower house elections in Victoria, Queensland, and South Australia assisted the longevity of premiers such as Henry Bolte, Joh Bjelke-Petersen, and Tom Playford, but these were hardly models of good electoral practice. It is hard to spot any majoritarianism here. Rather, these voting arrangements gave rural voters greatly more clout than their city cousins, thereby undermining democracy and promoting authoritarianism. In the case of Queensland, it contributed to an increasingly venal corruption.

Nor does Brett give sufficient weight to the contribution of compulsory voting to the decay of party rank-and-file membership. While the transition from a mass membership to an electoral professional model is not peculiar to Australia, political parties here have few incentives to develop their rank-and-file support because they do not need to get out the vote. They can ignore their base – the ‘rusted-on’ – while catering to the middle ground. This has the advantage of avoiding US-style polarisation, but it is questionable whether policy designed to appeal to a mass of disconnected, apathetic, and distrustful voters in the ‘sensible centre’ is necessarily the best recipe for good government either.

The ‘democracy sausage’ available to voters who turn up on election day reflects the largely peaceable and good-humoured nature of Australian elections. There is surely some irony that the compulsory character of mass participation provides voluntary organisations with an opportunity to raise funds by running barbeques and cake stalls. Brett has produced a paean to the Australian election, but her fascinating story of how we vote also discloses larger truths about what we are like as a people.

Comments powered by CComment