- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Original voices are always slippery to describe. The familiar weighing mechanisms don’t work very well when the body of work floats a little above the weighing pan, or darts around in it. As in dreams, a disturbing familiarity may envelop the work with an elusive scent. It is no different for poetry than for ...

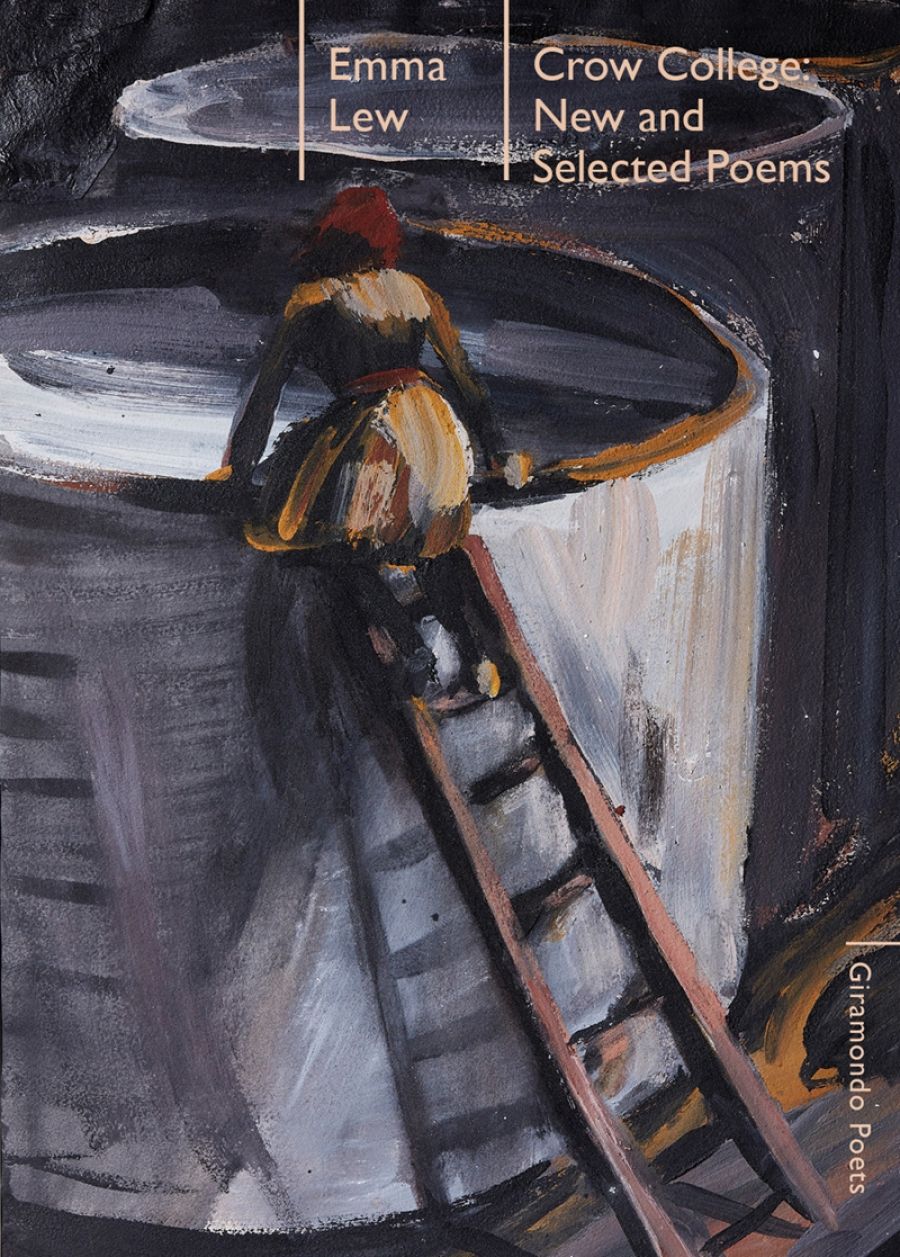

- Book 1 Title: Crow College: New and selected poems

- Book 1 Biblio: Giramondo, $26.95 pb, 144 pp, 9781925818055

Given the long hiatus since the last full-length collection, I was struck by the vulnerability of art, facing its audience; its existence is never assured. Reviewing Anything the Landlord Touches, Justin Lowe addressed the poet directly: ‘Why did you put pen to paper?’ The question is harsh. Lew’s poem ‘Trench Music’ gave one possible answer, ahead of the question: ‘I cannot evade these forms in the bone, / the slow tunes from oblivion. // I fill up with shooting stars: / let my human half sing out.’

Poets’ ‘forms in the bone’ take their shape from many sources. The dark hybridity of a poem may extend beyond its genre – in the directions of visual art, theatre, dance, sculpture, music. Art in any of these genres may be labelled poetic; but the converse feels less common: poetries that translate from the language of other arts into their own. The originality of Lew’s poetry comes from a hybrid lineage unlike any other Australian poet’s. Within it must be counted the visual arts and theatre, perhaps particularly of the German Expressionist period, and the irrational associations of absurdism and its descendants (highlighted by a recent Met exhibition, Delirious: Art at the Limits of Reason, 1950–1980). Reading a poem such as ‘Poem’, cited here in full, is like viewing a piece of conceptual art: ‘Decaying thunder, / all the ordinary rain. / A raft of tiny fools, / a poem of nails.’ August Strindberg’s A Dream Play (1902) may not be a direct source, but some of Lew’s monologues could readily have belonged in it. Many of Lew’s poems have the visual quality of tableaux, as if a voice were speaking within a painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder:

The children herding cows were so

beautiful.

One questioned me about the darkness.

Ships with all their sails, I said.

All the melodies of pain at every shift,

and then the endless moon, growing

and growing.‘Light Tasks’

Michael Brennan has acutely observed in Lew’s poetry ‘the ‘ferment and fury of history and consciousness … the recesses of times past’. Its exceptional visual and verbal qualities aside, one of the most striking aspects of the poems is, indeed, the sense of a historical consciousness. Lew’s histories are like fragments of fresco paintings on the walls of Russian churches: here, the broken detail of a robe, or a porch; there, a single eye gazing. The whole is unknowable (as any history is), but the detail is convincing. To see it makes one dream of other times.

Lew’s imagination is attracted to the underbelly of history. ‘Chernobyl: Small Talk’ speaks to the irrationality underlying certain political systems and personal anxieties: ‘I feel that I can trust you with a secret: / I’ve been ordered to fall in love with you / and I’m insanely worried about my eyes.’ ‘I’ve been ordered to fall in love’ makes oneiric sense against a backdrop of authoritarian politics; the comment about eyes is the sort of odd anxiety any lover might feel about a part of their body. Taken together, they conjure an Orwellian irrationality. While the name ‘Chernobyl’ suggests a relatively recent past, other lines in the poem give it a nineteenth-century feel: ‘Come over, the apples are ripe / in my guardian’s orchards.’

Orchards, guardian: it is hard to imagine both words being deployed in a modern sentence. By such subtle means – an astonishing sleight of hand – the poet transports us to an undefined yet queerly familiar time.

Crow College is graced with an excellent introduction by poet Bella Li. Though the guidance it gives the reader is deeply insightful, I missed the presence of endnotes. There are, no doubt, external touchstones, and it would help Lew’s readers to know what some of these have been. A brilliant early poem, ‘Of Quite Another Order’, draws on the real history of a ‘feral’ child, Victor of Aveyron, and the attempts to educate him – a story that a later poem, ‘Pali’, seems to touch upon again – but the source is not indicated. Many other poems draw apparent inspiration from scenes in Russian literature, which resonates with the heightened sensibility of the poems.

Poetry – whether of this nation or any other – is richer for the presence of Lew’s passionate voices and disquieting, historical sensibility – these tableaux situated, as the poem ‘Luminous Alias’ observes, ‘somewhere between serenity and vertigo’. Let’s hope to see more of this original art.

Comments powered by CComment