- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Paradise of dissent

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

I had never been to Adelaide in my life when I arrived for an interview that, as it turned out, would result in my spending the next twenty-five years in South Australia. The early November heat was too much for my Melbourne best suit, and I was carrying my coat when I walked gratefully into a city pub for a post-interview beer. In the bar – air conditioned down to a level threatening patrons with cryogenic suspension – I tried Southwark and then West End, finding both just drinkable, and lingered in front of a wall poster about the Beaumont children, by that time missing for nine or ten months.

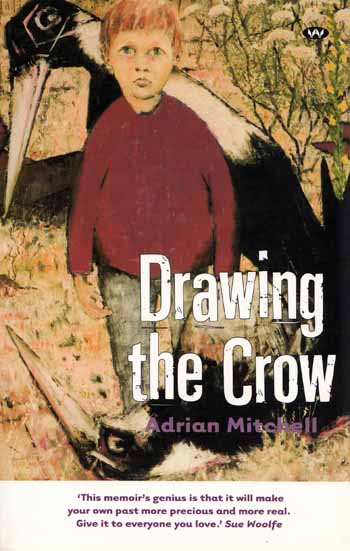

- Book 1 Title: Drawing The Crow

- Book 1 Biblio: Wakefield, $22.95 pb, 179 pp, 1862546851

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

It was, I realised much later, a rather Adelaide arrival, mixing flawless blue skies, unseasonable (by Melbourne standards) heat, mildly aggressive individuality (Southwark! West End!) and mystery, disappearance. In the twenty-five succeeding years I came to love, but could never quite specify the nature of the mix that constituted the palpable ‘difference’ about South Australia and Adelaide: ‘Paradise of dissent’ was certainly part of the answer, while Salman Rushdie’s bloodstained footpath was phoney portentous-ness born of Writers’ Week endorphins and who knows what other stimulants. Sometimes I thought I should have a stab at characterising Adelaide’s inimitable atmosphere. But now there’s no need. Adrian Mitchell has done it – and splendidly.

There are many good things about Drawing the Crow – an expression which, as Mitchell explains, ‘is not quite the same as drawing the short straw … [and] is better than a poke in the eye with a blunt stick; probably’ – but one of them is the sheer distinction of the writing. The trick about memoir is that events, people, details, minutiae, anecdotes that mean much to you and that you are confident will strike chords in your contemporaries must also be made to resonate for readers whose life experiences are very different, belong to a different time and arise from an entirely different ambience. There are a number of ways of accomplishing or at least attempting this, and one of them is to seduce with language, rhythm, wit and style. From the start, Mitchell strikes just the right notes:

These essays are not intended to be autobiographical, though what they tell is inevitably tethered to me. They are not about who I was but where I came from. It is axiomatic that nothing happened in Adelaide in the comfortably apolitical years of the Playford era, and these essays testify to that. There was just nothing much to write home about; and we hadn’t gone anywhere anyway. These essays attempt to represent a South Australian point of view, or something like a set of South Australian eyes, to put down on paper (injudicious phrase) how it was for us, growing up through the 1950s, and extending into the years before and after that decade, in a perfectly ordinary home, in a perfectly ordinary suburb, rediscovering the richness of it.

The wry concessions, the insistence on the ordinary, the stoic note and the quiet irony are all, we discover reading on, characteristic. So is the potent last phrase. The promised richness emerges, a full panoply of it, evoked brilliantly but without fuss, its unerringly observed detail often under-cut by the narrator’s refusal to be impressed by his own voice.

A stern insistence on the ordinariness of one’s tale, on its being ‘nothing special’, combined with ironic wit and a note of fatalism induced by the very details of the experiences can all add up to cynicism. When Mitchell confesses to being fascinated by the phrase ‘Cela m’est égal’, it is reasonable to wonder whether this is uttered as the stoic’s shrug or the cynic’s weary concession. But though both are involved, Drawing the Crow bows to neither.

‘The recollection of mere detail,’ Mitchell observes, ‘retrieved fact, memory of the pick-a-box sort, is of virtually no interest.’ Well, yes and no. This is just one example of a distancing manoeuvre that runs through the entire book: if just about everything is ordinary, on the verge of not being worth recording at all, you have to guard yourself constantly with disavowals of this kind. But they scarcely stand up against the power and evocation of detail-filled passages like this:

The stone farmhouse nestled in a hollow. The blond paddocks stopped at a low limestone wall mortared together but crack-ing apart, and an ancient box-thorn hedge; a picket gate had long since given up keeping the bantams out of the desiccated garden … Scratchy lavender bushes marked out a kind of path, and piece-rate worker bees hovered about them, trying to do a headcount. Pigeons preened and strutted on the roof-top, until chased off just before mealtimes by the new shift of silver gulls.

For all the ironic wit, the sometimes feigned – sometimes rigorous – detachment, the benign but piercing intelligence of the recalling voice, Drawing the Crow is, in the best, verdant, luxuriant meaning of the word, a lush narrative, because it gives so generously of its grasp on the past, the unsensational but intensely lived past. The pace slackens and the touch is less deft in the last couple of essays – perhaps because, written at different times, they lack the momentum of the others – and the conclusion is abrupt, though pungent. But this is, in its own small, undemanding way (Adrian Mitchell would presumably be pleased with those adjectives), a classic memoir.

Comments powered by CComment