- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Custom Article Title: Jacqueline Kent reviews <em>The Blackburns: Private lives, public ambition</em> by Carolyn Rasmussen

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

If you were young and energetic and a believer in a range of progressive causes, Melbourne in the first three decades of the twentieth century was an exciting place. It was even better if you were in love. Doris Hordern and Maurice Blackburn, the joint subjects of Carolyn Rasmussen’s deeply researched ...

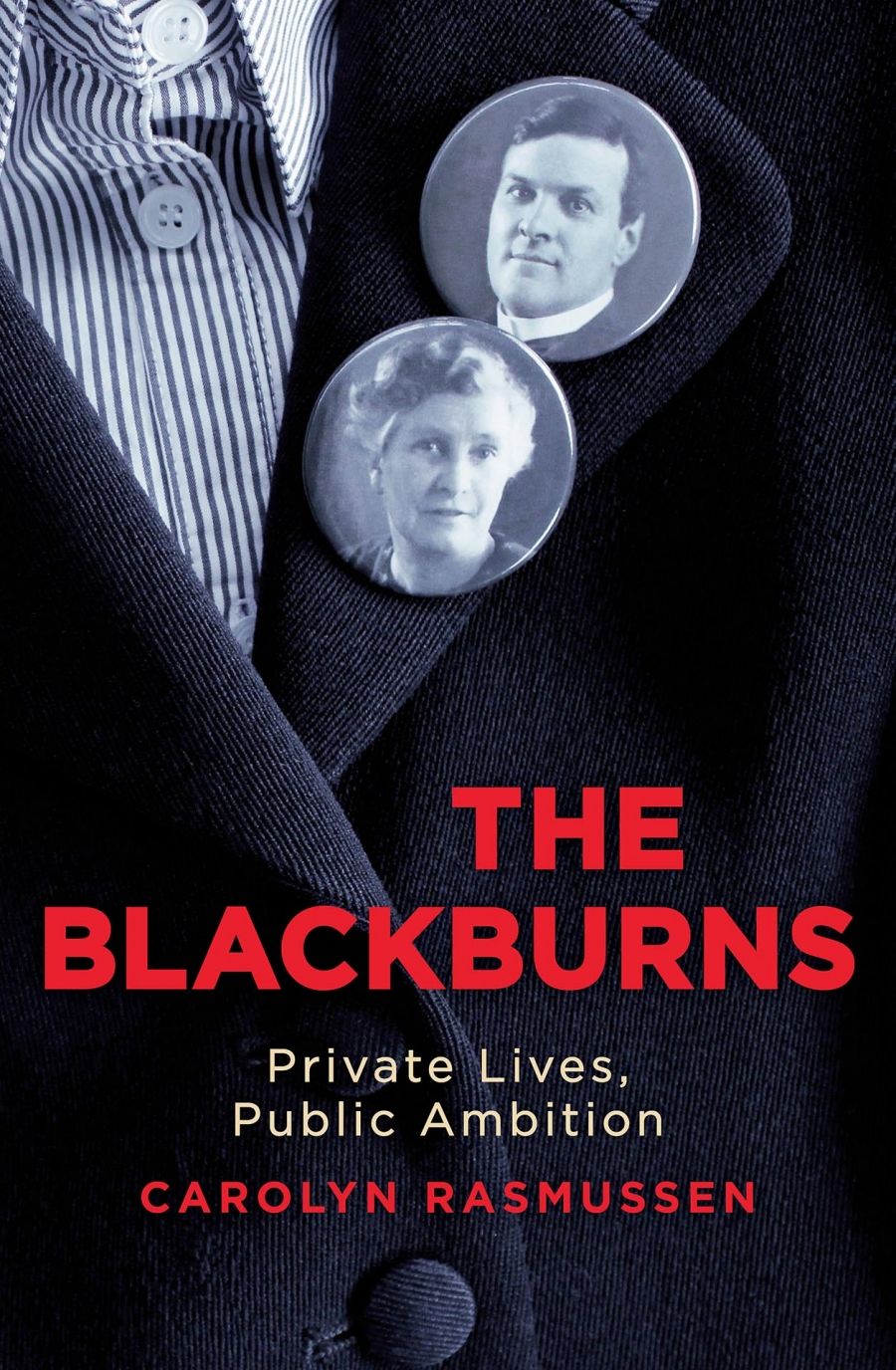

- Book 1 Title: The Blackburns: Private lives, public ambition

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $44.99 hb, 400 pp, 978022874457

Doris Blackburn with her administrative assistant Gloria Canet (National Library of Australia)

Doris Blackburn with her administrative assistant Gloria Canet (National Library of Australia)

Both were strong feminists, possibly because they were brought up by their mothers. Maurice joined Goldstein’s Women’s Political Association and began providing notes on law and politics for her newspaper The Woman Voter. Even though he was male and an active member of the Australian Labor Party – Goldstein was firmly against political parties – his willingness to help the cause made him the WPA’s ‘pin-up boy’. Relations frayed, however, when he and Doris became increasingly reluctant to follow Goldstein’s separatist line. Both Blackburns were also out of sympathy with the WPA’s opposition to compulsory military training with the outbreak of World War I, and Doris found the Women’s Peace Army much too confrontational.

Doris became involved in raising a family, taking on a supporting role to her husband. At this point, Rasmussen inevitably gives centre stage to Maurice’s impressive legal and political career. His juggling of the law and politics was not always successful; it was once said of this rather intellectual, bookish man that he would walk his own path, even if other people were moving in the same direction. His son once observed that Maurice was ‘one of those people who stuck to his guns and if people didn’t like it, well, he would go his own way’. Not an organisation man, then, which hampered his career in the Australian Labor Party.

Maurice was often in conflict with the ALP. His support for compulsory army training cost him state preselection in 1917. Though a socialist himself, he opposed the party’s socialist objective. (He eventually succeeded in having it modified, and it became part of the party platform.) However, he was a popular and successful state and later federal MP. His constituency was inner Melbourne, and he pursued a great range of local initiatives, especially on behalf of those less fortunate. He was president of the Victorian branch of the ALP and Speaker of the House of the Victorian Parliament, and became a federal MP in 1934, where he remained until he was defeated for preselection nine years later.

Rasmussen goes into necessary detail about Blackburn’s career, but sometimes her description of his trajectory is not easy to follow: she occasionally jumps backwards and forwards in time, giving the results of certain initiatives before the processes that created them. However, the history of Australian labour relations is a complicated and often fraught one, and she gives a clear picture of the conflicts involved. She is always persuasive about the beliefs that drove Blackburn, and his actions.

She is on more straightforward ground when it comes to Doris Blackburn. Rasmussen gives us a portrait of a woman of ‘boundless physical exuberance’ who, among other things, liked rowing a small boat in a strong current against a headwind – an excellent metaphor for a professed political idealist if ever there was one. Doris did not much enjoy domestic life or motherhood with growing children, and she was less demonstrative than Maurice. She cherished literary ambitions; Rasmussen quotes some of her sweet, heartfelt verse, including one or two poems that hint at thwarted ambition.

As time passed, Doris and Maurice Blackburn drifted apart: though both took an active part in the interwar peace debates, Maurice largely occupied the masculine world of the labour movement, which Doris never found congenial. Nineteen thirty-one was a horror year; a newborn daughter, Doris’s father, and her favourite sister all died. In trying to cope with her grief, she shut Maurice out; she also invited Frank Murphy, an old friend, to live with the family for three years. Rasmussen passes lightly over this, but it does cry out for more discussion of Blackburn family dynamics and relationships.

After Maurice’s death, Doris, aged fifty-five, achieved an exceedingly satisfying goal of her own. In the 1946 election she won her husband’s old federal seat of Bourke, becoming the first woman independent MP in the Australian Parliament, forty-three years after Vida Goldstein made her first attempt. She was a lonely figure, shunned by her ALP colleagues (partly because she loathed Arthur Calwell and the White Australia policy, which she said had been formulated to exclude Asians). She stood firmly against the Woomera rocket range and nuclear testing in peacetime, and developed a strong and lasting concern for Aboriginal welfare and equal rights. She lived to see the passing of the 1967 referendum granting full citizenship to Indigenous Australians.

In her introduction, Rasmussen states that one of her goals in writing this joint biography was to release Maurice and Doris Blackburn from other people’s footnotes. In presenting this fleshed out, likeable portrait of two vital, influential people who deserve to be more famous than they are, she has succeeded admirably.

Comments powered by CComment