- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Theatre

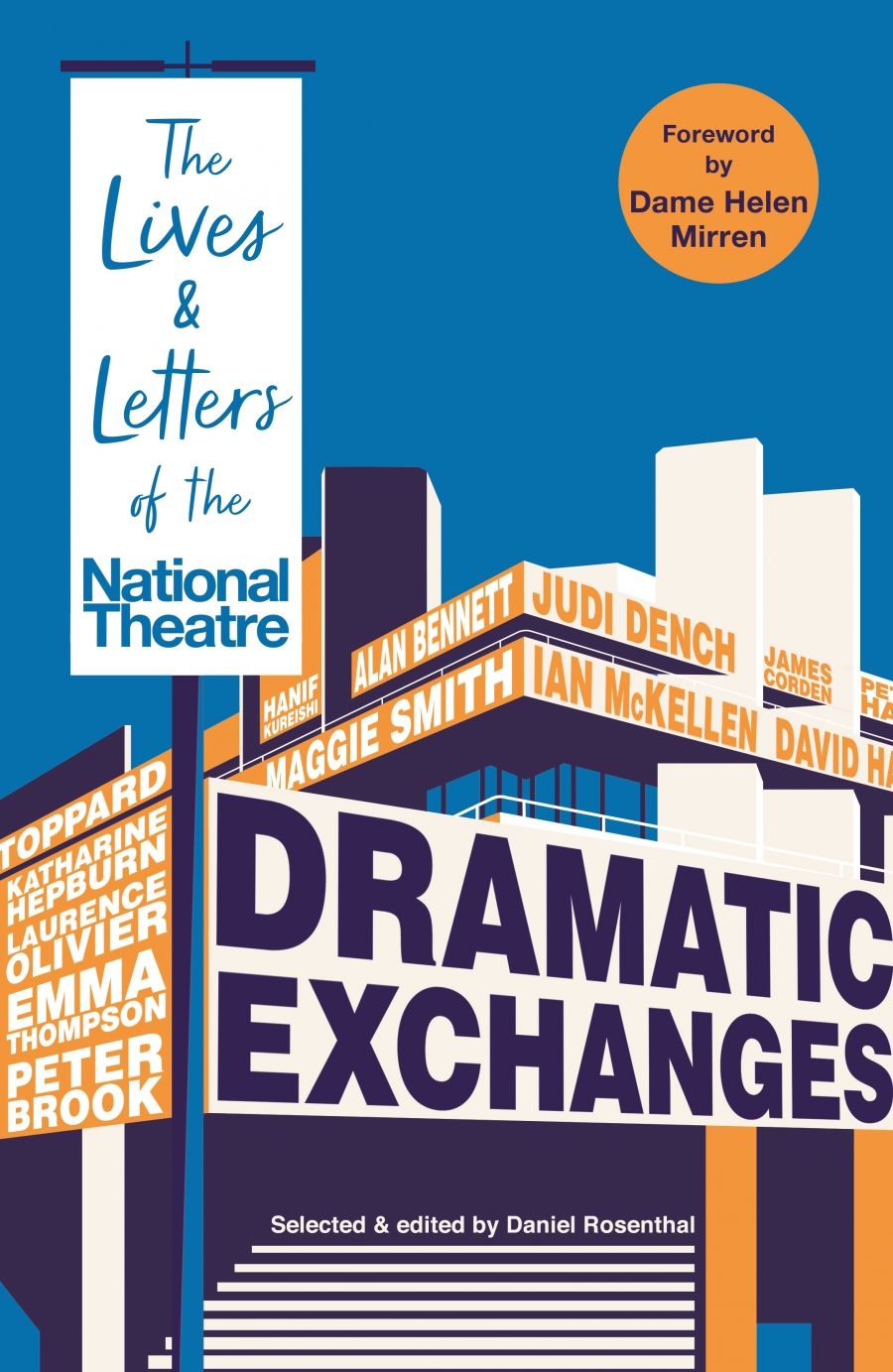

- Custom Article Title: Ian Dickson reviews <em>Dramatic Exchanges: The lives and letters of the National Theatre</em> edited by Daniel Rosenthal

- Custom Highlight Text:

What exactly is a National Theatre for? What is its purpose? What form should it take? National theatres come in many configurations. There is the four-hundred-year-old Comédie-Française serenely presiding over French culture from the Salle Richelieu. The Habima Theatre of Israel ...

- Book 1 Title: Dramatic Exchanges: The lives and letters of the National Theatre

- Book 1 Biblio: Profile Books, $49.99 hb, 416 pp, 9781781259351

The National Theatre in London at night (photograph by Ben Sutherland/Flickr)

The National Theatre in London at night (photograph by Ben Sutherland/Flickr)

At the same time as Laurence Olivier took on the task of founding the National, the exceedingly ambitious twenty-nine-year-old Peter Hall was staking out a claim for his Royal Shakespeare Company in London by taking over the Aldwych Theatre. As they circle each other, their correspondence degenerates from the polite to the terse. ‘If your new empire is going to set out to kill Stratford and my Company,’ Hall writes plaintively, ‘then what will have been achieved except the usual British waste?’ ‘You know very well that I do not want and never would allow anything to “kill” Stratford except over my dead body,’ Olivier replies, ‘and you really mustn’t throw up words like “Empire” to me, not you with Strat., Aldwych and now Arts … At the moment [taking on the National] looks to me like the most tiresome, awkward, embarrassing, forever-compromise, never-right, thankless fucking post that anyone could possibly be fool enough to take on and the idea fills me with dread.’

Apprehensive he may have been, but Olivier assembled a dazzling group of actors, mixing the already renowned, like Peter O’Toole and Michael Redgrave, with those who would become stalwarts of the profession, like Derek Jacobi, Lynn Redgrave, Michael Gambon, Robert Stephens, and Colin Blakely, whose early death deprived the theatre of one of its greats. Olivier developed a complicated relationship with Maggie Smith, who, until she joined the company, was known mainly as a West End comedienne. Although relishing the éclat her increasing fame brought to the company, he also appears to have been wary of her growing star power. His prompt scheduling of William Congreve’s The Way of the World, the play Smith most wanted to perform, the minute she took a break from the company and giving the part of Millamant to Geraldine McEwan was an act of bastardry that elicits from the anguished Smith one of the most powerful letters in the collection. Dame Maggie compensated by bestowing a magnificent Millamant on the lucky audience at Stratford, Ontario.

A continuing theme during both Olivier and Hall’s stewardship was the luring of the skittish Paul Scofield to the National. Their persistence triggered at least three great performances – for Olivier, Wilhelm Voigt in The Captain of Köpenick and Leone Gala in The Rules of the Game; for Hall, Salieri in Amadeus.

Olivier’s company performed at The Old Vic while the new building was being erected, but, like Moses, who never reached the Promised Land, much to his fury Olivier was denied the chance to lead his team into it – though equating Denys Lasdun’s forbidding concrete bunker with the land of milk and honey is perhaps a step too far.

Peter Hall, with his formidable drive and proven administrative abilities, was an obvious choice to take the company from a building with one theatre to a building with three. One of the continuing themes of the book is the way directors confronted Lasdun’s awkward spaces, adapted to them, and finally conquered them.

After a decidedly shaky start, Hall’s regime came into focus, but critics were always ready to attack. Peggy Ashcroft came to Hall’s defence when the Evening News attacked him under the heading, ‘A National Disaster’: ‘It is a sad thing in this country we should be so ready to blame, criticise and never to celebrate achievements. It would amaze many foreigners and dismay our own theatregoers … to have [the NT] labelled “a National Disaster.” Fortunately they know better.’

One of the major triumphs of Hall’s tenure was Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus, but Shaffer must have come to rue the perils of success. He is the recipient of an incendiary letter from the originally chosen director, the acerbic John Dexter, with whom he fell out over the matter of royalties. Later, after the enormous success of the play, he becomes the target of Peter Hall’s wrath when the play’s actual director discovers he will not be the director of the film version.

Throughout the book it is perhaps the relationships between directors and playwrights which fascinate most. Richard Eyre’s championing of David Hare’s massive state of the nation trilogy, Trevor Nunn’s shepherding of Tom Stoppard’s equally ambitious The Coast of Utopia, and Nicholas Hytner’s bantering relationship with Alan Bennett have produced works that, whatever success they have had elsewhere, needed the impetus of the National to launch them. It is good to see this sort of relationship continuing with Rufus Norris, the present director, and Carol Ann Duffy.

Dramatic Exchanges, as its title suggests, concentrates on the artistic side of the National and leaves us unaware of the ways in which the directors, Hytner in particular, attempted to branch out to as wide an audience as possible. Hytner brought in outside companies, made cheap tickets more widely available, and introduced NT Live. Norris, who persuaded Duffy, Britain’s poet laureate, to adapt Everyman for him as his inaugural production, later worked with her on a collaborative piece based on extensive interviews from ordinary people around the country. My Country: A work in progress was the result: it played the Dorfman Theatre at the National and then toured, and the correspondence between Norris and Duffy ends the book.

Norris’s National Theatre may not be a theatre without walls, but it is at least making attempts to break out from its concrete mausoleum.

Comments powered by CComment