- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

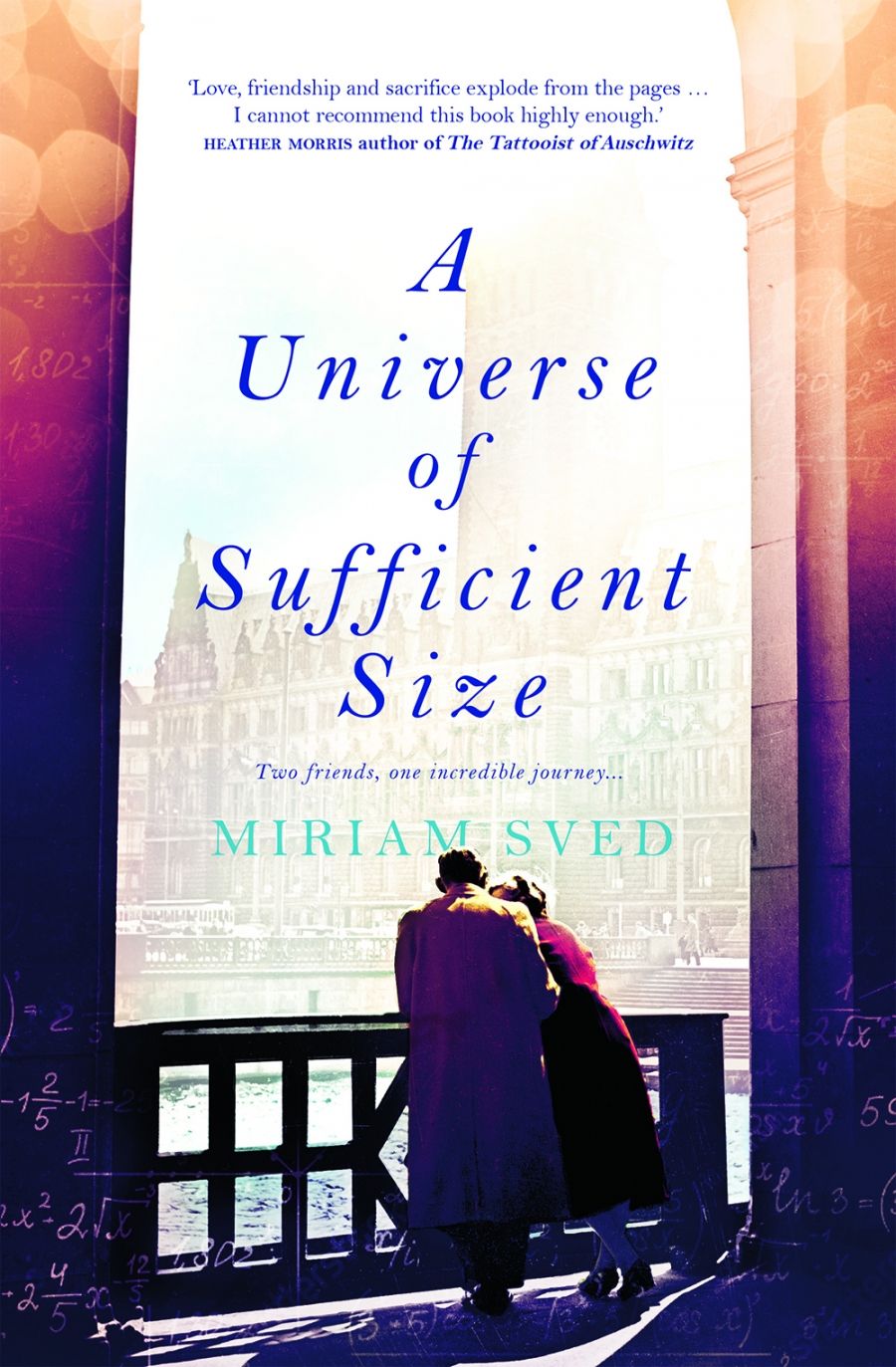

- Custom Article Title: Naama Grey-Smith reviews <em>A Universe of Sufficient Size</em> by Miriam Sved

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

At the front of Miriam Sved’s A Universe of Sufficient Size is a black-and-white photograph of a statue. The cloaked figure holding a pen (‘like a literary grim reaper’, reflects one character) is the statue of Anonymous in Budapest, a significant setting in the book. Its inclusion is a reminder that the novel draws on the story of ...

- Book 1 Title: A Universe of Sufficient Size

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $32.99 pb, 314 pp, 9781743535127

Miriam Sved (photograph via Pan Macmillan Australia)

Miriam Sved (photograph via Pan Macmillan Australia)

The plot unfolds through intertwined storylines. The pre-war narrative is told in epistolary chapters set in Budapest in 1938. These alternate with a contemporary narrative set in Sydney in 2007, which follows Illy Hughes, her children, Josh and Zoe, and her elderly Hungarian mother. When Illy’s mother gives her a mysterious notebook, the connections between the two narratives begin to emerge, with Sved expertly controlling the story’s pace.

While the 1938 narrative holds the mystery, the 2007 study of family dynamics is often in the foreground. Despite the Hughes family’s challenges, moments of humour and tenderness abound. University student Josh relates to his Nagymama, or grandmother, through a shared love of mathematics, but the reader is also aware of a parallel between the chaotic love triangles in each of their lives. Meanwhile, rebellious Zoe’s activism, sexuality, and tattooed comrades from a women’s circus concern her mother, but the reader is also privy to Illy’s doubts about her own suburban life.

Mathematics play a key role in the novel, and offer a vehicle for Sved to explore its themes. The mathematicians’ ‘upper limit problem’ – their search ‘for meaningful order in what at first appears to be random chaos’ – is rich in symbolism: Sved’s characters repeatedly face moments of upheaval in a world whose shape is no longer familiar. For Eszter, this happens at Hirig Simon, a ritual beating of Jewish students in Hungarian universities. When Eszter’s classmates turn on their Jewish peers, she reflects: ‘so this is what the world is. This was there all the time, only loosely restrained by some semblance of civilisation.’ Similarly, when Pali Kalmar tries to share his mathematical insights with a Viennese professor who ‘wanted to talk Jews instead of mathematics’, Pali is ‘wrenched out of his beautiful abstract world into the harsh light of reality’. Sved relates these paradigm shifts back to the central metaphor of seeking patterns in randomness, meaning in chance, order amid chaos. The novel’s title is a reference to the theory that complete disorder is impossible given a large enough set.

Though Sved confesses to having a ‘mathsless brain’, she excels in evoking the beauty and wonder of mathematics. Technical passages could easily have been laboured in the hands of a lesser writer, but Sved (with the help of mathematician Tony Guttmann) resists the temptation to over-explain, instead offering brief, relevant, convincing references. The result is a story that bristles with the joy of mathematical inquiry.

Along the way, Sved weaves insights into the role of art in understanding the world around us. Zoe is a photographer, and Illy harbours a dormant passion for sculpture. When Illy’s husband summarises the metaphorical meaning of her artwork in a single line, Illy wonders: ‘if what she’d experienced as a clamour of disparate feelings could be trussed and nailed so easily, then what was the point of it really?’ It’s a poignant reminder that the power of art is experiential, not didactic.

When Zoe questions her grandmother about the past, wanting ‘a label, some ordering classification’, her Nagymama resists easy answers and reflects inwardly that ‘There is a sturdier order than names underlying things, an identity known in the skin.’ So it is with Sved’s reimagining of her own grandmother’s past. Sved rejects neat delineation, instead offering many types of chaos in which identity is fragmented and multiple. In the book’s dedication to the memory of Marta, ‘who loved mathematics and also stories’, Sved hopes that her grandmother ‘wouldn’t mind the liberties I’ve taken with both’. There is a sense of care, custodianship even, in Sved’s reimagining of the story that inspired it, in making it her own while honouring its essential truths – its sturdier order.

Comments powered by CComment