- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

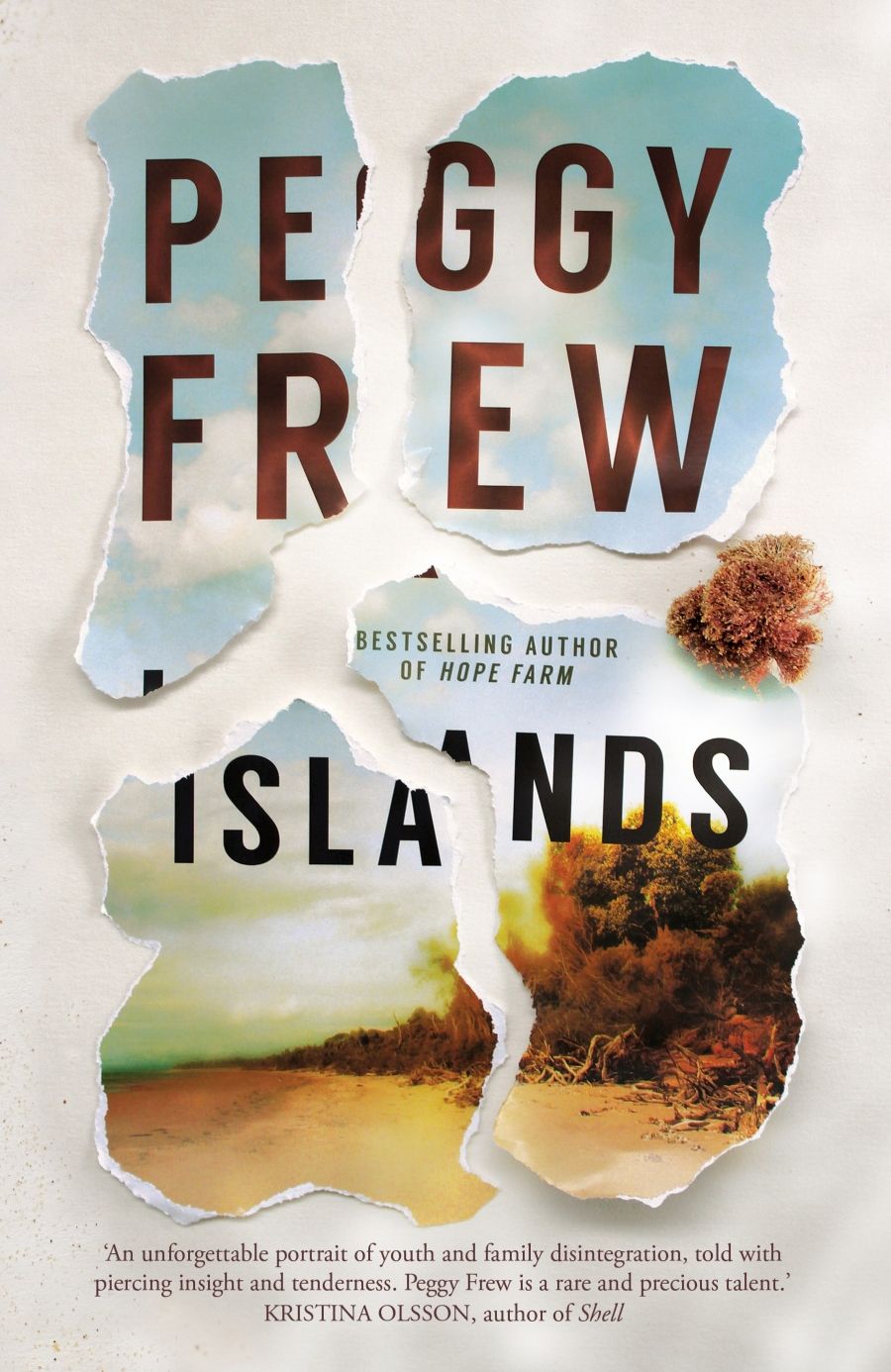

- Custom Article Title: Bronwyn Lea reviews <em>Islands</em> by Peggy Frew

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

According to the AFP, two Australians under the age of eighteen are reported missing every hour. Most are found alive, fairly quickly, but an unlucky few will progress to the category of long-term missing persons. From the Beaumont children of the 1960s to the more recent disappearance of toddler William Tyrrell ...

- Book 1 Title: Islands

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.99 pb, 320 pp, 9781760528744

Peggy Frew (photograph via Scribe Publications)

Peggy Frew (photograph via Scribe Publications)

The title, in its most basic interpretation, points to Phillip Island off the coast of Melbourne where the Worth family – Helen, John, and daughters Junie and Anna – spent their summers before the split. The landscape is drenched in memories of Anna, whose presence is felt ‘on the beach, in the dunes, in the scrub, in the garden, on wet black Settlement Road at first light, under rows of cypresses, and in spider webs and in waves and in the flights of birds, and in the silent inching open of the moon behind clouds’. A more figurative reading of the title, however, sees the family shattered by tragedy into an archipelago of individuals, each bound by a discrete consciousness and unsharable experience. ‘The world is of our own making.’ the existential narrator tells us. ‘Nobody else can know it.’

Despite thematic similitudes, Islands is not another mystery or thriller to toss on the towering pile of missing-daughter novels. Frew’s literary ambitions can be located in her fashioning of a non-linear narrative that leaps haphazardly back and forth in time to visit events, from Helen’s rural childhood in the 1960s to Junie’s present-day life as a painter, mother, and hapless wife. Bent on frustrating the narrative, Frew focalises successive chapters through alternating characters and deploys a miscellany of testimonial genres in the telling: diary entries, lists, gallery-wall texts, psychological transcripts, and mental cogitations collapsing syntax into poetry. Such devices, well executed, offer the prospect of kaleidoscopic storytelling, but, in sacrificing intimacy to multiplicity, they can induce detachment and risk disorienting the reader through structural omissions, unresolved tangents, and a general lack of clarity. Inclined toward the latter, as more often is the case in Islands, we arrive at the novel’s resolution without catharsis.

One thing, however, is abundantly clear: everything is the mother’s fault. At least her family thinks so. Helen’s principal function, it seems, is to serve as a receptacle for their blame, shame, and animosity – much of which is filtered through misogynistic critiques of the female body and libido. Helen’s sexuality, refusing to be curbed or redirected into a sexless motherhood, becomes their bête noire. Unrepentant, Helen comes in for such a heavy dose of slut shaming that by the end of the novel – despite a notably short list of attractive character traits – she becomes its most sympathetic character.

Junie, whose stated life goal is not to be her mother, has a particular hostility for her mother’s body. To her mind Helen’s flesh – ‘lush’, ‘greedy’, ‘shameless’ – is grotesque. She tries to ignore it, she insists, but it’s always there: ‘a hungry soft monster wanting sex’. Junie’s aversion to her mother’s body is so strong that, years later when Helen is old and sick, she still cannot ‘bring herself to touch this creature’. Even John, at one time the beneficiary of his wife’s physical appetites, holds her sexuality responsible not only for the breakdown of their marriage but, less credibly, for Anna’s mental debilities and, ultimately, her disappearance.

What is a family to do with memories of a missing child? Do they enshrine the child at the age of their disappearance? Or do they count birthdays – Anna would be forty if still alive today – in the hope that their loved one is somewhere on earth growing older? One of Frew’s strengths as a writer is her inclination not to offer easy answers: ‘Of course I had to move on,’ Helen argues in defence of her record. ‘But giving up, that’s something different. Giving up hope, I mean. You can’t, even if you want to. I’ve wanted to!’

Another of Frew’s strengths is her ability to translate the natural landscape into language. Islands ends with a dark place where Anna liked to go: ‘The sun begins to shine. Everything goes lacy, glossy, and steam comes up from the earth.’ She keeps walking.

Comments powered by CComment