- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Photography

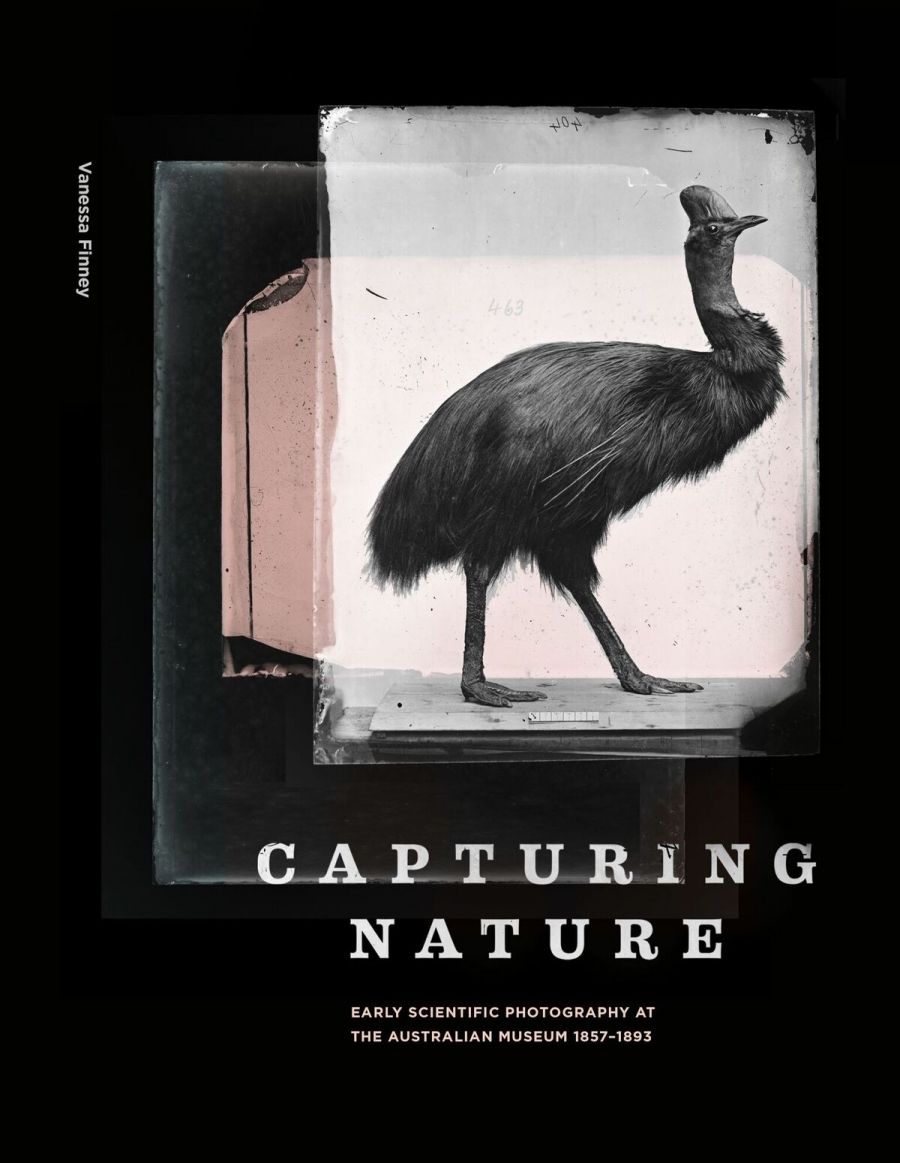

- Custom Article Title: Philip Jones reviews <em>Capturing Nature: Early scientific photography at the Australian Museum 1857–1893</em> by Vanessa Finney

- Custom Highlight Text:

The photographic resources of museums and their archives have emerged as key sources for studying the natural world and human cultures, particularly as those studies have widened to include the techniques and modus operandi of scientists and anthropologists themselves. Their notebooks and field equipment ...

- Book 1 Title: Capturing Nature: Early scientific photography at the Australian Museum 1857–1893

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth/Australian Museum, $49.99 pb, 200 pp, 9781742236209

Greater Flamingo, Phoenicopterus roseus. This flamingo skeleton was presented to the Museum by the trustees of the Zoological Society of New South Wales (Taronga Zoo) in 1893 (photograph by Henry Barnes)

Greater Flamingo, Phoenicopterus roseus. This flamingo skeleton was presented to the Museum by the trustees of the Zoological Society of New South Wales (Taronga Zoo) in 1893 (photograph by Henry Barnes)

Krefft was one of a cadre of influential German scholars and scientists working in Australian museums during the nineteenth century. He was quick to see the potential for photographic documentation of natural history specimens whose form and structure could not be easily maintained once collected. Fish were the prime example; watercolour drawings had been the preferred method for recording different species, but this required an artist on hand, and unless they were particularly accomplished the drawings could not be relied upon. During the 1880s the South Australian Museum employed an artist (August Saupe) to make and colour plaster casts of fish, but this was expensive and time-consuming. Despite lacking colour, Henry Barnes’s fish photography at the Australian Museum left no doubt as to accurate species identification. Finney has included a fascinating series of his images, crisp and sharp, each with their series number etched onto the glass negative. There seems little doubt that the Australian Museum board, composed of naturalists such as Alexander Macleay and George Bennett, who were themselves avid collectors of Sydney Harbour fauna, including fish, appreciated the introduction of a technique that would allow those fugitive characteristics to be instantaneously preserved with such clarity. Significantly, board members each received copies of the museum’s photographs during the 1860s and 1870s.

Here it is worth mentioning that practically all the images included in the book were first generated on glass plates, initially through the ‘wet plate’ process in which the photographer was required to undertake the full sequence of chemical steps once a glass plate was exposed. As Finney’s colleague Vanessa Low explains in a clear exposition, the introduction of the ‘dry plate’ process from 1881 enabled the development process to occur later, relieving the photographer from the necessity of lugging heavy but delicate equipment wherever they went. Finney doesn’t say as much, but it seems clear that her careful and fascinating record of the Australian Museum’s internally generated photography collection derives from her archival processing of these glass plates. Similar collections were generated in other museums at later times and in several government agencies (survey, railway, health, for example), but not all of those collections have survived. A museum’s own propensity to accumulate its records rather than superseding and discarding earlier forms has been a crucial factor in this instance. The Australian Museum’s collection of glass plates survived intact well beyond its first period of use, almost forgotten and certainly overlooked, until Finney herself instituted a program to digitise the collection, a revelatory process which forms the basis of this book and the exhibition it accompanies.

After being preserved by taxidermists in an outdoor workshop in 1883, the huge sunfish specimen entered the Museum via the tallest available opening: an upstairs window (photograph by Henry Barnes)

After being preserved by taxidermists in an outdoor workshop in 1883, the huge sunfish specimen entered the Museum via the tallest available opening: an upstairs window (photograph by Henry Barnes)

The book contains several themes and stories beyond that of the documentary role of museum photography. Finney has broadened the content to include a narrative of the Australian Museum’s first curators and technicians, in which Gerard Krefft’s own extraordinary biography features. Krefft’s tribulations and achievements, and his overt support for Darwinian theory soon after it reached Australian shores, provide a compelling vignette. She also explores the relationship between scientific illustration and photography and the ways in which the early photography of museum exhibits leads us into an understanding of the art of museum taxidermy as practised during the late nineteenth century.

It is often difficult to achieve the right balance in a book of this kind, not only in terms of the ratio between image and text, but in the exposure and detail of the images themselves. In all those aspects, Finney has been well served by a fine design team and by the photographer, James King, whose scanning and rendering of the original images take us directly back to the decisive moments when the shutter button was pressed. To me, as a historian tuned to the museum subject, this is an exciting volume, primarily for the ways in which it opens the field of museum documentation itself as a vital element of scientific enquiry. There is a lot more investigation ahead, particularly in terms of differentiating the various categories of museum photography and understanding their respective roles. Ethnographic photography seems to have been skirted a little timorously in this volume, and the apologia for its absence seems to rely a little too much on current orthodoxies, but that is a minor cavil, for this volume admirably meets its stated purpose: capturing nature.

Comments powered by CComment