- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

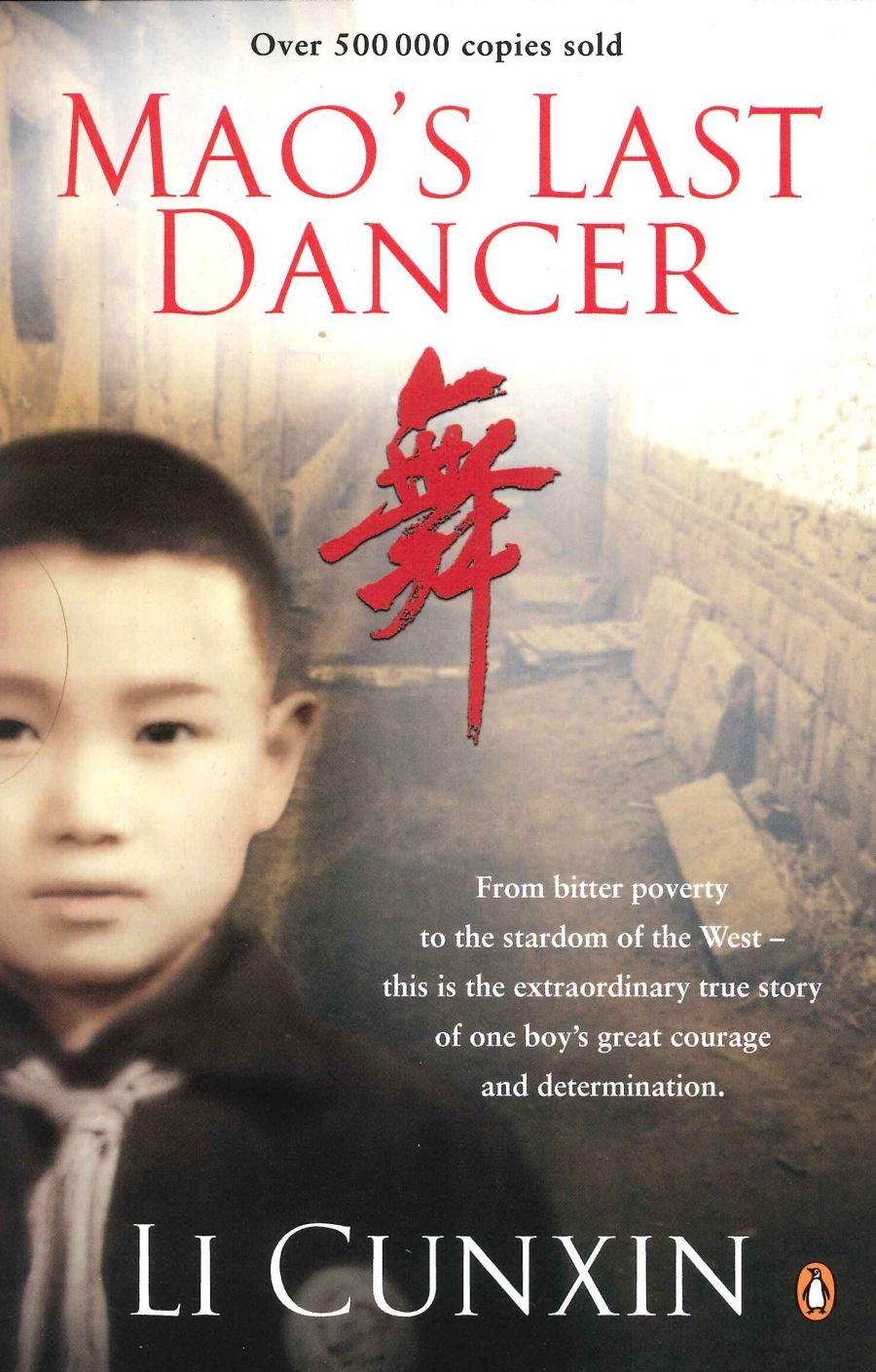

- Custom Article Title: Robin Grove reviews 'Mao’s Last Dancer' by Li Cunxin

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There were seven of them, as in a folk tale. The family was too poor to put shoes on their feet. They lived in a village called New. Hard though life was, they knew it would be worse without Kindly Leader, who was carrying the land into prosperity and joy. At present, however, the seven sons had little to eat.

- Book 1 Title: Mao’s Last Dancer

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $29.95 pb, 460 pp, 067004024X

That determination, and its collision with what resists it, is central to the story of Mao’s Last Dancer. But alongside it is the figure of ‘my niang’, the beloved mother, the ‘live treasure’ who fed the family, washed, contrived, joked, suffered, and was the sun that gave energy to her galaxy of men. Cunxin’s resistance to the systems of oppression was sustained by the constant presence in his mind of the Li family and of his undauntable mother above all. The book is like a testimonial sent home, or a letter to the deepest part of himself in the years of growing up.

At the start, in 1972, he feared and hated Madame Mao’s Academy. But it was a choice between the ballet’s ‘cage of rules, routines, frustration’, all endured in ‘an agony of loneliness’, and the frog-well of the village. Sensibly, he took the middle course, and did as badly as he could without being forced to leave. From 1974, however, though the place was still a brutal cadet camp, its potential gift of freedom began to materialise: life and dance got better, both at once. Despite the instructors’ abusive régimes (‘Gao Dunkan pushing our bodies onto our legs with the full force of his weight’), the fluidity, airiness, brilliance, and intellectual light promised by classical technique gradually became available, and so did friendships and respectful admiration of pupil for teacher, and vice versa.

It would be pleasant to suppose that at this point the folk tale could resume and tell how the prince took the road of art and reaching the sunny pinnacle once seen from far below. The book does not permit such fantasies. It reveals how the fierce strategies of the ballet school were internalised by students, to emerge as self-punishing routines: hopping upstairs with a sandbag around their ankles; doing back-somersaults that almost killed them; always driving themselves. By degrees, the academy’s plan for breaking the body became their own measure for mastering it. An equivocal victory, at best – as even the valedictory speech of Teacher Xiao makes us realise:

You’re Chairman and Madame Mao’s last generation of dancers. You have studied under the most strict and disciplined rules imaginable, but this will give you an edge over the others. You’ll be the last dancers of the era.

Meanwhile, if bodies were given a hard time, minds were similarly fortified by political self-marshalling. After being one of Mao’s young guards, the fourteen-year-old Li was invited to enter the Communist Youth Party, a rare privilege. It was no ordinary student, therefore, who appeared with the Houston Ballet in 1979. Mao’s China was offering its best. But all the young communist could see was that the West of refrigerators and hot showers was everything the East of village labour was not. American goods were costed by reference to his father’s wage; the material super-abundance of Chapter 18 was set against the terrible outpouring in Chapter 13 from his brother Cunyuan, trapped at home:

burning sun, pouring rain, freezing snow, empty stomach, seven days a week . . . My dreams are the only comfort I have, and most of those are nightmares. I’m twenty-four years old! There is no end to this suffering!

Li never forgets the generational miseries of peasant life. Ballet may be art, but it is above all a means to escape: ‘the one thing I knew how to do’.

Inevitably, therefore, when the time comes, he seizes that chance. Invited to return by the Houston Ballet in 1981, he defects – on behalf of suffering China, if also for his own future. The ‘powerful sense of belonging’ he once felt, of being ‘wholeheartedly embraced by the Communist Youth Party’, is now turned against him, the Chinese vice-consul simply announcing, ‘You’re the property of China. We have given you everything. We have the power to do anything we want with you.’ What that leaves out of account, however, is the fact that, if Li belonged to China, in a more important sense China belonged to him, through the depth with which his identity was planted in the family and the village called New.

Li places little emphasis on his dancing career, his international reputation, his time with the Australian Ballet. His memoir, as its title says, is about one of Mao’s dancers. In the peasant villages, the waste pits overflow or freeze solid. Four to a bed, people sleep head to toe; the animals starve to death; and the beloved Chairman and his devotees promise that this first stage of communism will lead to an ‘ultimate wonderland’ of ‘total happiness’. The fantasy was ‘like morphine for the sick. It gave us a reason to bear our present harsh conditions.’ But it could not withstand the reality of selfish, opulent, luxurious America or the reality of his family’s life, where the only thing put on the table any night might be ‘north-west wind’ for dinner.

This moving and extraordinary tale combines tenderness with strength, just as Li Cunxin’s dancing still lives in the mind’s eye, unique in its blend of softness and moral power.

Comments powered by CComment