- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Get Porter

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

All young persons contemplating ‘a life in the law’ as a career should read this book, ideally when they are about sixteen, to allow adequate time to switch to dentistry, say, or engineering. But whatever your age, Chester Porter’s huge experience, wisdom and humanity will enlighten you about the true inwardness of those sometimes compatible concepts, justice and law.

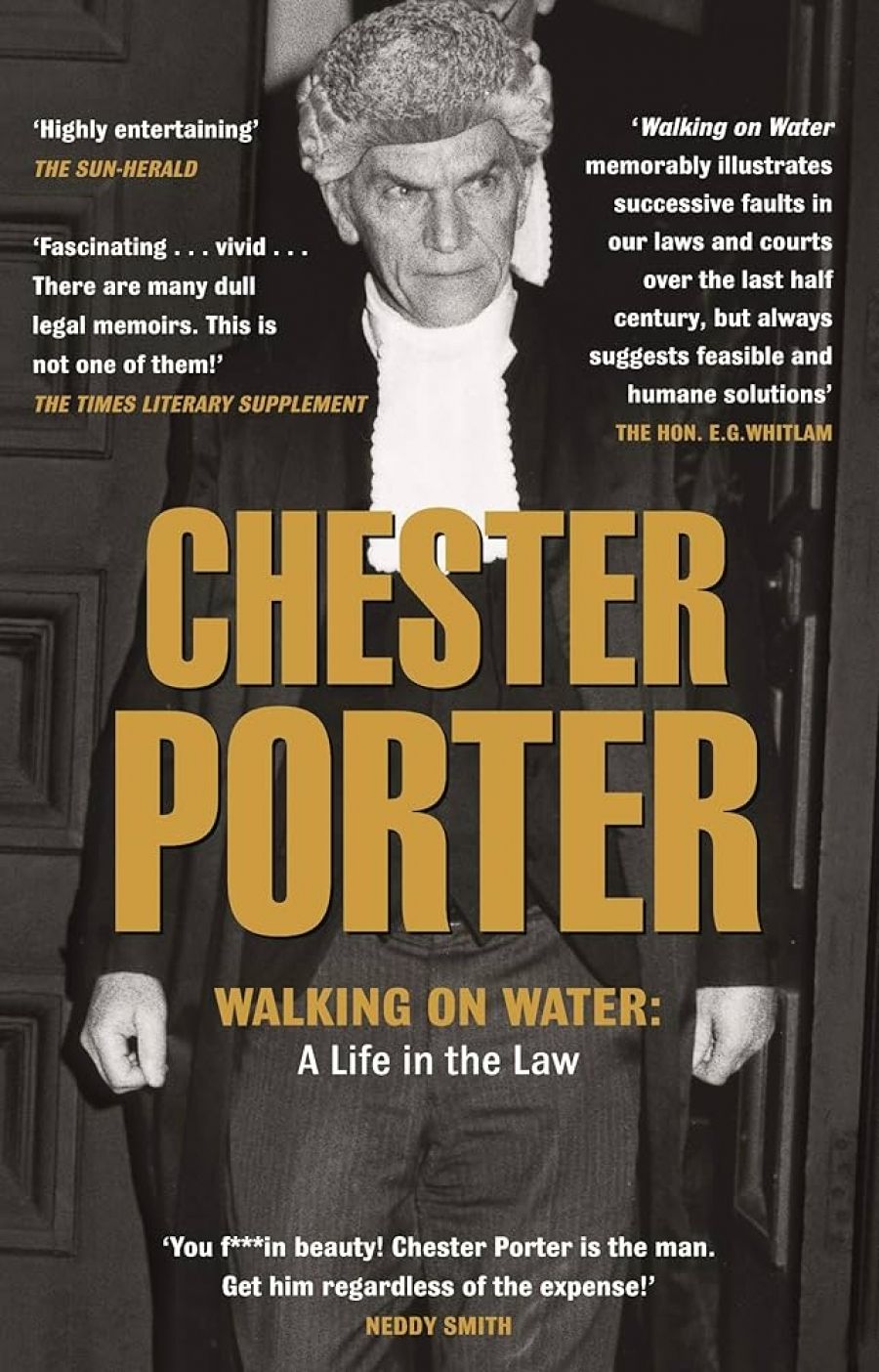

- Book 1 Title: Walking on Water

- Book 1 Subtitle: A life in the law

- Book 1 Biblio: Random House, $49.95 hb, 319 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The phrase ‘walking on water’ undoubtedly describes the opinion many barristers hold about their own hours in chambers and in the courts, but no such delusion of divinity afflicts Chester Porter, QC. He joined the New South Wales Bar in 1947 when he was twenty-one, the youngest barrister ever admitted. He practised there for half a century without interruption, except during a serious injury from a motor accident.

He appeared in, or was involved with, a great proportion of the most famous cases of his time, including many Royal Commissions. Some, like the notorious bent Sydney detective Roger Rogerson, were local celebrities. Others commanded the legal headlines of the nation, such as the Lindy Chamberlain case; the second Royal Commission into the Voyager naval disaster; High Court Justice Lionel Murphy, and Judge John Foord, charged with attempting to pervert the course of justice.

Porter commanded high respect and high fees. How does he then feel today about the prime accolade bestowed by a satisfied client, the unattractive Sydney underworld monster Neddy Smith: ‘You fucking beauty! Chester Porter is the man. Get him regardless of the expense!’?

A reviewer can best convey the book’s flavour by picking out some plums – there are many:

In the practice of the law, you find human nature at its worst, angry and in dispute. Divorce (now coyly called ‘family law’) is the jurisdiction where ‘bastards and bitches prosper’. Lionel Murphy’s matrimonial legislation, on the whole, made matters worse, and increased the instability of social life.

Porter says that the rich generally avoid their share of taxation, and probably always will. He believes that the real leaders of the drug trade are never caught, and never will be; that they regularly and deliberately betray a proportion of their dealers lower down the line to help the police bump up their apparent ‘success’ rates and to deceive the public into thinking that ‘something is being done’. The true basis of the wholesale price of petrol will never be disclosed. The criminal justice system makes it easy for an innocent person to be convicted. In many sex cases, an innocent man is gaoled, and has his life blasted.

Porter laughs at the idea of the ‘inestimable benefit’ supposed to be enjoyed by the original trial judge, who can watch the demeanour of the witness. Eyewash! Cunning witnesses put it all over judges every day. He says that lie detectors, fingerprints and DNA may all be unreliable, as well as much of the psychological evidence solemnly swallowed by the bench. He is cynical about today’s mass of paper heeled by the trolley-load into court, of which but a tiny proportion may add enlightenment or truth. Much of it is simply flimflam from the rich and well-resourced litigant, put in merely to crush the small suitor under the expense.

These distillations of Porter wisdom make a life in the law sound like a daily trudge ankle-deep through human ordure, but there is nonetheless a brighter side. Women judges have improved the temper and quality of the bench, and female jurors have lifted the standard of verdicts. Australian courts of appeal are among the best in the world. A better magistracy rates as a great success story of Australian legal reform.

Porter’s plain prose might score high on the George Orwell literary scale, but it lacks sparkle and zest. He comes across, on his own telling, as a decent, steady, kind and patient man, without whom the law would be even more dreadful than he shows it to be. He seems relieved not to have been appointed a judge. Maybe that is society’s loss.

By authentic ‘book people’, both Porter and his publisher will be convicted and severely sentenced: there is no index, in a book replete with names, cases and leading facts; no sign that a skilled book editor ever got within a bull’s roar of his manuscript. Not only are there innumerable repetitions, but repetitions of repetitions. For all that, the book is splendidly printed, without a single typo to be found.

We should all read Walking on Water and be better educated, and no one should embark on litigation before they have done so. By the time they lay the volume down, they will have cooled off, left their solicitor untelephoned, saved themselves a bucket of money and averted a heart attack.

Comments powered by CComment