- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Reviews

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Unlocking Dupain

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It is interesting to recall the number of times, in book titles alone, that Max Dupain’s name has been linked to ‘Australia’. Joining Dupain’s own Max Dupain’s Australia (1986) and Max Dupain’s Australian Landscapes (1988), this new book is the third in a series by his former printer and assistant Jill White. Dupain’s Australians joins the similarly all-inclusive titles of Dupain’s Sydney (1999) and Dupain’s Beaches (2000). The pairing of Dupain with aspects of Australia says much about how we position this photographer as quintessentially ‘local’. Despite his evident contributions to modernism and, I would argue, classical modernism, it is Dupain’s apparent ability to capture a ‘national essence’ that still dominates accounts of his work.

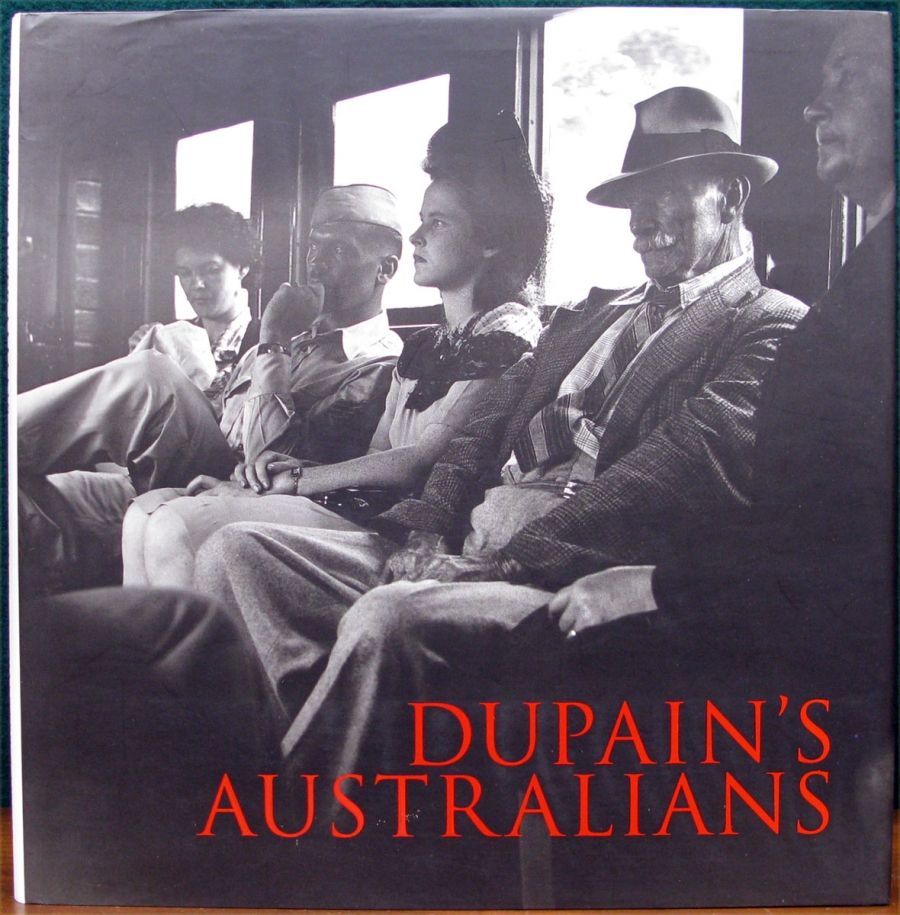

- Book 1 Title: Dupain’s Australians

- Book 1 Biblio: Chapter & Verse, $70 hb, 112 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Books on Australian photographers are sufficiently unusual to be noteworthy, particularly expensively produced, lavishly illustrated and beautifully designed ones such as this volume – though Dupain has had his fair share of attention in recent years. Given another bite at this relatively limited market, the question has to be asked: how does this book add to our knowledge of Dupain’s work? More particularly, how does it take advantage of a rare emphasis on that important and productive phase in Dupain’s career, the 1930s and 1940s?

On the positive side, it contains some little-known and interesting portraits. Divided into mini-chapters and lovingly reproduced, there is a wonderful series of photographs from the so-called ‘Parer album’, which Dupain sent to the cinematographer Damien Parer in 1940. With its delightfully relaxed and intimate shots of a young, newly-wed Dupain and his bride, Olive Cotton, these portraits form an interesting contrast to Dupain’s more usual formal portrait style. Indeed, one often gets the feeling that Dupain’s evident skill with portraiture masked a discomfort in dealing with people he did not know. In an interview with Craig McGregor late in his life, Dupain stated: ‘I like few people … [To] go into a room full of strangers is a chore for me.’ Something of this uneasiness must have relayed itself to his sitters because, unless they are close friends or family, or are taken in a documentary mode without the sitter’s awareness, people appear inaccessible and often slightly uncomfortable.

Contextualising this range of portraits is an essay by Frank Moorhouse that suggests we should approach the work through the perspective of ‘craft, nostalgia and key-holes’ – the last, rather curious phrase, referring to a perspective on the past that is without the viewer’s direct memory of the period. Moorhouse acknowledges, however, that it is with the ‘craft’ or the aesthetic aspect that Dupain himself would have preferred us to focus, and the impassioned writings of the young photographer (not to mention the older and no less fiery version) certainly suggests this to be the case. Dupain clearly considered himself as part of the avant-garde in the 1930s. A sentimental approach to either art or life was not his style.

From the positing of nostalgia as a way to connect with these historically situated photographs, Moorhouse moves into more problematic territory. In a section called ‘Sources of Dupain’s Aesthetic’, he turns to the question of whether Dupain’s work shows the influence of social or political issues. While raising the issue of vitalism – a philosophy that, through the books of Norman Lindsay, influenced Dupain – Moorhouse concludes that there is no evidence of such a perspective. He not only states that he can find no evidence of any of the ‘potent ideologies of the day’ in these photographs but that, extraordinarily enough, Dupain may be ‘sans doctrine’. If the work contains any taint of doctrine at all, Moorhouse concludes, it is a kind of humanism that shows Australia as an ‘ordered and now mellow normality’.

Well, all I can say is that Moorhouse didn’t look too hard for evidence. There is in fact a surfeit of visual data to show that Dupain was profoundly influenced not only by vitalism but, just as importantly, by the ‘body culture’ movement of the 1930s and 1940s. This wide-ranging and popular movement was underpinned by nationalist goals and by a desire to revitalise the body and society according to eugenic principles of health and fitness. This may sound extreme, but consider that Dupain’s father (a formative influence) was an active promoter of ‘selective breeding’ not only before but also after World War II. The spectre of ‘decadence’ – a key phrase in the eugenicist’s vocabulary – was also an intrinsic part of Dupain’s practice.

To choose only one, albeit characteristic, quote by the photographer that shows his awareness of such issues – in 1940 Dupain wrote:

Paul Gauguin fled to Tahiti to revolt against the degenerate sophistication of Parisian life. A little later the ‘dark otherness’ in D.H. Lawrence cried out against the intellectualising of the deeper instincts in man. Forty or so years have passed since they uttered their hatred of this decadence in human society; since then certain spartan influences have grown and perhaps the ‘heightened physical awareness’ they yearned towards has developed to some extent.

For Dupain, like his father, the solution for revitalising depleted Australians lay in their reconnecting with nature: the beach, nudism and surfing all helped create healthier individuals and, ultimately, a ‘fitter’ society.

It is time we interrogated the matter of ‘Dupain’s Australia’ more closely. What passes for images of an ‘ordered and now mellow normality’ in fact masks something darker – and far more interesting. Without the deep perspective that underpins much of Dupain’s work of the 1930s (most notably his nudes), we are condemned to see his work eternally locked into a sentimental and nostalgic perspective. Does this broadened view deny Dupain’s role as a key modernist photographer and creator of stunning images? Not at all. In fact, I believe that it enlivens our understanding of his photography, not to mention the period in which he worked. Far from existing in some rarefied and discourse-less vacuum – ‘elevated to iconic status’, as Moorhouse says – these are photographs taken by a complex man, and which, in turn, reflect the complex political times in which he lived.

Comments powered by CComment