- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Reviews

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Guarding the Oeufs

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Assuming the Chair of a business regulatory authority might not be thought of as an ideal path to media stardom, but Allan Fels showed otherwise. Fels is easily Australia’s best-known cartel buster and the scourge of price-fixing business and anti-competitive behaviour generally. For years he was regularly on the nightly news. In a savage sea of rapacious price-gougers, Fels was the consumer’s friend.

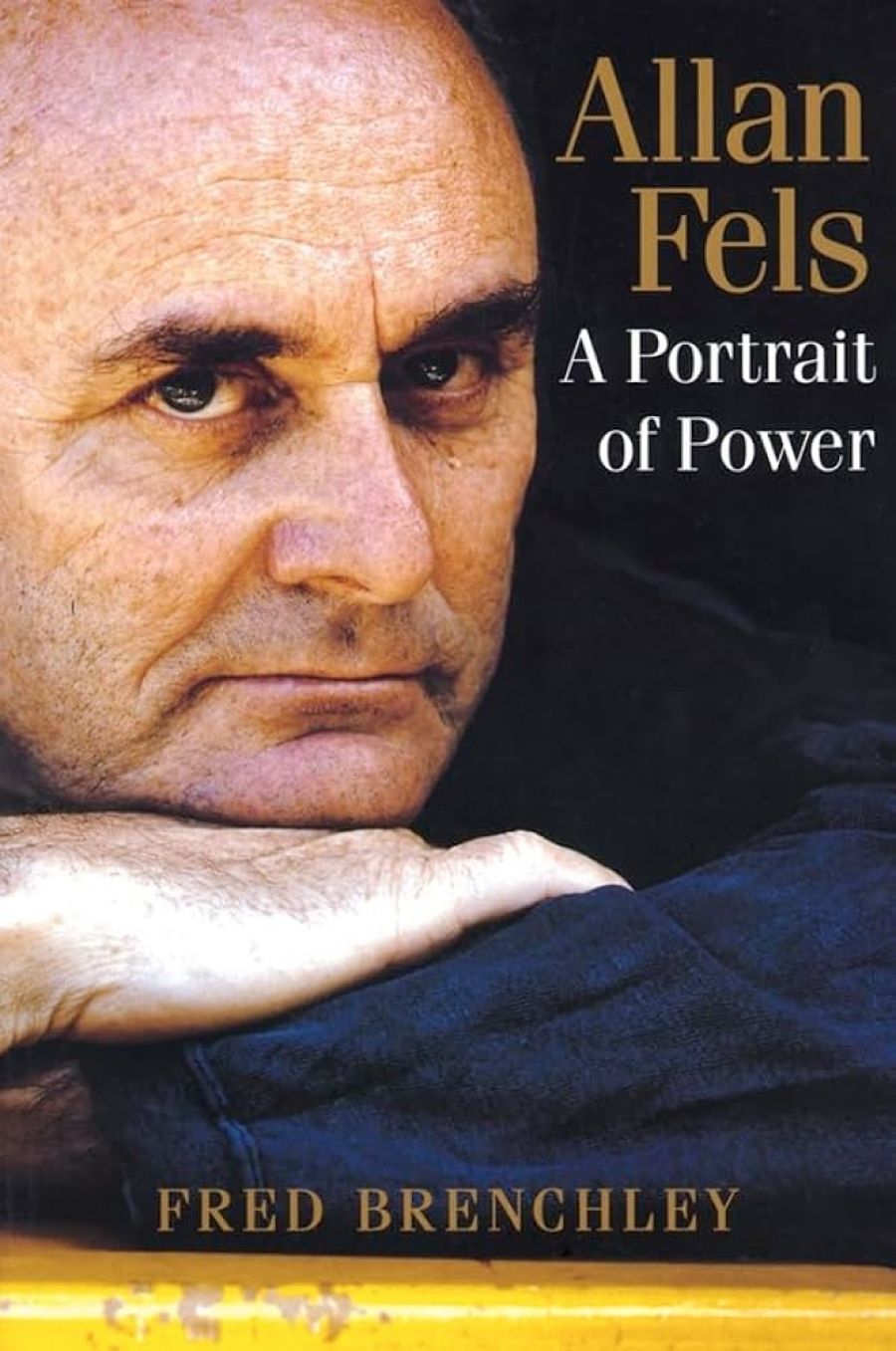

- Book 1 Title: Allan Fels

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Portrait of Power

- Book 1 Biblio: John Wiley, $29.95 pb, 310 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

While he may have been a darling with the media, his relations with sections of business, including the publishing, music and media industries, were frequently poisonous. This relationship even extended to the near torpedoing of this very book. The book industry showed that it was quite prepared to cut off its commercial nose to spite its face when it came to Fels.

As Brenchley points out, ‘With Fels’s Robin Hood image and his ranking as one of the most powerful people in Australia – not to mention his being the only Canberra regulator ever to make Sydney society’s A-list – his story would appear to have all the ingredients for a popular book.’ This was not how publishers saw it. Proposals for this book drew negative reactions from publishing houses. Eventually, Penguin showed interest. A contract was drawn up, but later suddenly withdrawn by the publishing director, Robert Sessions. He told Brenchley that his fellow directors had vetoed the book because of their strong personal antipathy to Fels, who, they felt, had tried to scuttle their industry. The incident shows just how far some sections of business were prepared to take their hostility towards the regulator.

Fels’s approach to the book industry was similar to his approach elsewhere. He had turned it upside down, breaking down juicy import cartels and forcing lower prices. His ultimate aim of fully opening the Australian market to parallel imports has still not been fully realised, because of Democrat intransigence in the Senate.

Fels was Chairman of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission for twelve years, from 1991 to 2003. He was not idle. In that time, the ACCC instituted proceedings against corporations in 271 cases, winning ninety-four per cent of the disputes that went to court. A glance over the workload shows that almost every industry sector was represented: banks, insurance companies, transport, petrol, the media and the professions. Well-known companies and organisations such as Colonial Mutual, Telstra, Master Builders’ Association, TNT, NRMA, Ampol, Woolworths, Chubb Security, K Mart, NAB and Sony Music were targets.

Fels was at the forefront of the great economic changes in the 1980s and 1990s as the Australian economy opened up, internationalised and grew more flexible. The first Hawke government, in particular, energised the process that saw Australia abandon the old ways of cosy business cartels, high tariff barriers and protected industries. Subsequent reforms under the Keating and Howard governments have continued the process of modernising the Australian economy. The fact that Australia has weathered recent international crises shows that the reforms have produced a more resilient economy.

Fels and the ACCC fought for the benefits of competition to flow to consumers. He highlighted the urgent importance of firm competition policy as a discipline on the market. Was he successful? As a person who raised the media profile of competition regulation, undoubtedly so. But has the ACCC lifted Australia’s economic performance?

As Brenchley says, it is not an easy question to answer because the actions of the ACCC are not directly measurable in terms of economic growth.

But the wider economic picture of which the ACCC was a key institution shows rapid growth, higher GDP per person and falling prices in key infrastructure areas such as telecommunications, electricity, rail freight and port charges.

In some ways, Allan Fels was an unlikely media success. He had a rather flat and considered method of delivery, and his voice was often high and reedy. As someone who frequently interviewed him, I found that he could be a bit dull. Nevertheless, the subject matter was always engaging, and Fels’s image as a credible regulator with impeccable academic credentials was a winner with listeners. He also had a sense of humour and was fond of a joke. While chairing an inquiry into egg prices in Victoria in pre-ACCC times, he declared that the egg-regious prices must end. ‘An oeuf is an oeuf.’

His use of the media was critical to Fels’s success. It did not endear him to his political masters, and it is clear that his successor at the ACCC, Graeme Samuel, will adopt a less visible approach. Whether he will be as effective remains to be seen.

Fels was born in Western Australia of German Catholic parents in 1942. It was, he says, a ‘middle, middle class’ upbringing. His father managed a soap manufacturing business, which prided itself on making soap that the company boasted was ideally suited to Western Australian water – a claim that might have earned the scrutiny of Fels’s ACCC.

Religion was a powerful early force on Fels. So was cricket, at which he excelled. He went to university and studied arts/law, later switching to economics/law. Interestingly, for one who has often been seen as allied to the Labor side of politics, Fels dabbled in Liberal party politics and was a member of the party’s state council. He thought of a political career, but was disillusioned by the WA party’s factionalism, its position on Vietnam and the constraints of the party line. He opted for the academic life instead.

Daryl Williams, later to become attorney-general of the Commonwealth, beat him to the state’s Rhodes scholarship to Oxford. In 1966 Fels headed to Duke University in the US for further economics research. The workload was intense. Then came Cambridge, which changed his life. He became absorbed in prices and incomes policies and the possibilities of regulation that would control inflation.

It was this interest that led to the notion of competition policy as a more effective tool for controlling abusive market power.

There was an over-abundance of academic talent at Cambridge in those pre-Chicago School times; in 1972 Fels headed home with his Spanish wife, Maria-Isabel Cid, and their two children to begin a new life in Melbourne. For Maria in particular, the outer suburbs of Melbourne were a challenge.

Brenchley ably charts the rise and rise of Fels as a prices and incomes expert at Monash University, and his friendship with Bill Kelty at the ACTU, which became a springboard for Fels’s rise to the top of Australia’s regulatory bureaucracy. The prices and incomes accord was, of course, a key policy plank of the first Hawke government. He provides detailed treatment of the case that epitomised Fels’s use of the media and the one that earned him the loathing of Australia’s petrol industry – the Caltex raid of 2002. For Fels, the case was ultimately a disaster, but, as Brenchley ably demonstrates, it was a textbook example of the Fels style. The book also deals well with a personal tragedy in the Fels’s life and a reason for Allan’s retirement: the long-undiagnosed schizophrenia of their eldest daughter.

Brenchley clearly admires Fels and what he has achieved. The book demonstrates that there is much to admire. It is an admirable chapter in the history of Australia’s economic life.

Comments powered by CComment