- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Among the Chinese

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The opening scene of From Rice to Riches has the author travelling in a taxi with a camera crew through the city of Bengbu in China’s central Anhui province. A furtive glance in the mirror of her powder compact convinces Jane Hutcheon that they are being followed by Chinese officials. Determined to escape their pursuers in order to obtain the interviews needed for an investigative report on the pollution of the nearby Huai River, the crew twice changes taxi before diving into a crowded street market.

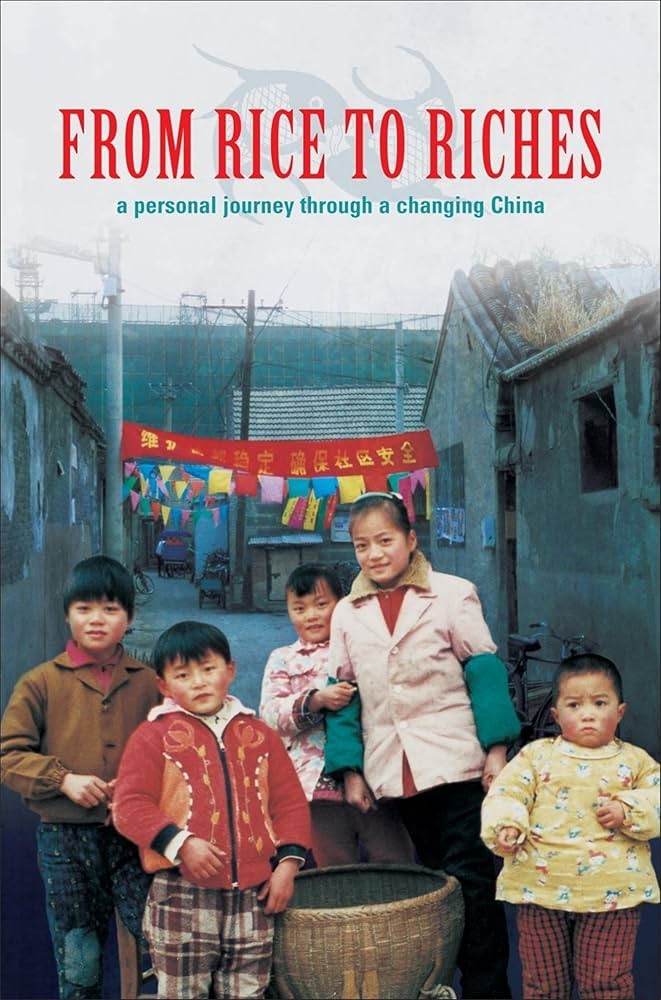

- Book 1 Title: From Rice to Riches

- Book 1 Subtitle: A personal journey through a changing China

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan, $30 pb, 371 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

It is a fitting introduction to a book that is largely about journalism and the means by which journalists – in this case, foreign correspondents – get their stories. That the setting is China, where Hutcheon was the ABC’s correspondent from 1995 to 2000, serves to enhance the journalistic dimension, since much of the book is concerned with the subterfuge needed to evade or outwit officialdom and to record the views of ordinary Chinese people. The book deals with Hutcheon’s impressions of the major events and issues preoccupying China during her posting, including the handover of Hong Kong from Britain to China in 1997, the tenth anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre and the preparation for the Beijing Olympic Games in 2008. But a persistent theme is the resourcefulness and tenacity needed by Hutcheon, her cameraman, the late Sebastian Phua, and the rest of the ABC crew to get perspectives on these developments at variance from the official Chinese version.

Journalists often turn to writing books – occasionally fiction, biography or history, but more often memoir and autobiography based on material gathered during their assignments. The urge to create something more ‘permanent’ than journalism drives many of its practitioners. Hutcheon, it seems, is no exception. She comes from a family of journalists: her father, Robin, is a former editor-in-chief of the South China Morning Post, and her brother Stephen was the Sydney Morning Herald’s Beijing correspondent in the mid-1990s. Hutcheon’s decision to join the ‘family trade’ was a happy one: ‘I could indulge my insatiable curiosity about the way people live, fight, survive, die, create and destroy.’ That curiosity was evident in the doggedness with which Hutcheon pursued her subjects in China, often venturing out alone to a location with a hand-held camera rather than risking the safety of the rest of the crew, and using disguises such as the black wig and spectacles she donned for an interview with members of the Falun Gong spiritual group.

As the book’s subtitle suggests, however, Hutcheon’s journey through China is not only journalistic but personal. Born in Hong Kong to a Eurasian mother and Anglo-Celtic father, Hutcheon’s links with China date back to 1851 when a distant uncle, Phineas Ryrie, a Scottish tea-merchant, arrived there. Hutcheon and her siblings had a comfortable, middle-class upbringing in The Peak area of Hong Kong. Her childhood, she readily acknowledges, was both sheltered and privileged. After studying journalism in Australia, she returned to Hong Kong and began her career as a reporter on local television. She began to see how the underprivileged lived, and also covered the negotiations over Hong Kong’s return to China, then the major issue preoccupying the colony. After five years, however, Hong Kong felt too small, and Hutcheon sought new challenges elsewhere. But she was determined to return to Hong Kong and to report on the handover for a foreign media outlet. In 1997 she achieved that goal.

Other features of the posting proved less satisfying. When she returned to China in 1995, Hutcheon hoped to understand what had drawn her ancestors to its shores and to discover the essence of ‘being Chinese’. These hopes were only partly fulfilled. Despite her Chinese background, Hutcheon was an outsider, subject to the same restrictions and constraints as other Western journalists. When she tried to eat a dish of slippery braised pig’s face (food is a recurring metaphor throughout the book), she found the experience frustrating and disillusioning, but ultimately rewarding. One of the most refreshing aspects of Hutcheon’s memoir is the candour with which it charts the evolution in her attitude from nostalgia for a colonial past to an acceptance of modern China on its own terms. She begins by trying to relive her ancestors’ adventures, but comes to love the country for less deep-rooted reasons.

Not surprisingly, her favourite city is Shanghai: her parents grew up there, and Hutcheon’s admiration for the progressive, entrepreneurial and Westernised spirit of the modern city is unmistakable. Yet she appears as much at home among the human and animal inhabitants of Xiao Cun, a small rural village she visits for a story on the mass internal migration from the country to the city; or slurping noodles in the dingy Beijing home of Pang Meiqing, a crippled survivor of the Tiananmen Square massacre. As China races towards capitalism and greater engagement with the West, insights such as Hutcheon’s are sorely needed.

Comments powered by CComment