- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Behind the Poppycock

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

I first met a refugee from Laos, a teacher in her former life, while working part-time in a miserable egg-packing factory in the early 1980s. I had only a hazy notion of what had brought Ping to this country. Christopher Kremmer’s Bamboo Palace has now clarified those circumstances, and what a sad and painfully human story it is: of a 600-year-old socially iniquitous, politically benign kingdom destroyed and replaced by a totalitarian state.

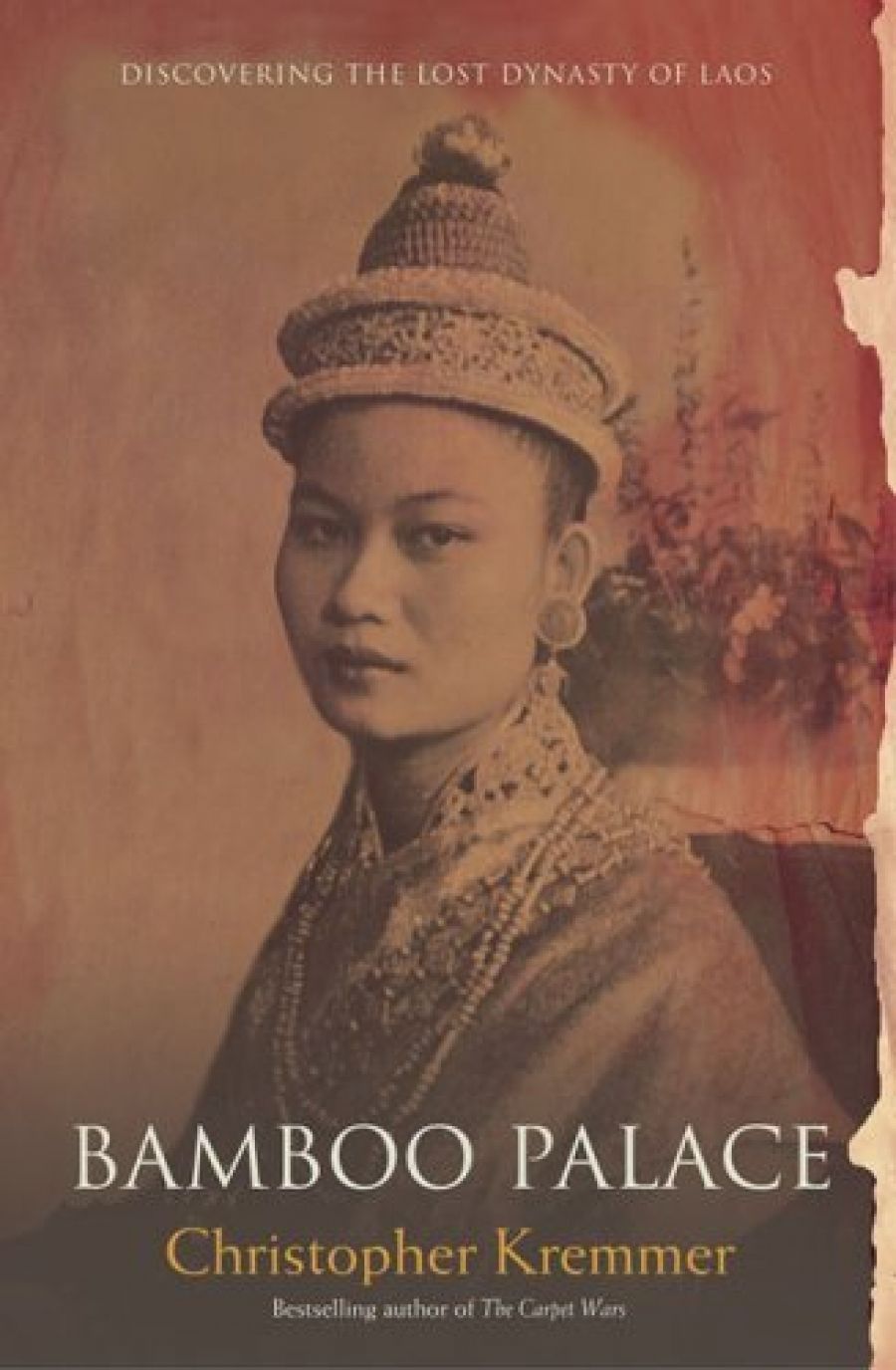

- Book 1 Title: Bamboo Palace

- Book 1 Subtitle: Discovering the lost dynasty of Laos

- Book 1 Biblio: Flamingo, $29.95 pb, 267 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Ping, it turns out, was fortunate, as thousands of Lao who were sent to ‘re-education’ camps after the Pathet Lao Communist takeover in 1975 learnt nothing but starvation and torture. It is usually the ‘political’ prisoners that suffer most, and so it was in Laos. Here, Kremmer tells us what happened to Khamphan Thammakhanty, a ‘hard-working and incorruptible’ intelligence officer in the Royal Lao Army, who was incarcerated in a prison camp in the north-east for fourteen years. Of his original group of forty, only four survived. Thammakhanty wrote his memoir after his emigration to the US in 1990, and it must stand for so many who did not have either his luck or his stubborn ability to endure. He and his 300-page testament, written in Lao, were brought to Kremmer’s attention after the publication of his first book on Laos, Stalking the Elephant Kings (1997). But it took Kremmer five years to realise that he had been given the key to a mystery that had intrigued him and everyone else interested in the country: the fate of the last Lao king and his immediate family, who apparently vanished in 1977.

Stalking the Elephant Kings was a lively and comprehensive account of Kremmer’s ‘personal journey’ to Laos, undertaken when he was a foreign correspondent based in Vietnam. Bamboo Palace does reward those coming to the story for the first time, but readers of the earlier volume are likely to feel a strong sense of déjà vu. Kremmer has not revisited Laos; instead, he has lightly redrafted the original, into which Thammakhanty’s story (fleshed out during many emotional interviews) has been neatly spliced – an ingenious solution to the obvious problem of publishing the memoir in its entirety, and a happy outcome for both authors.

Kremmer talked to many Lao government officials, and conjures up these people well. One in particular stands out: Sisana Sisane, a founder of the Pathet Lao, who, perhaps because he had ‘mastered bombastic Bolshevik poppycock’, became its Chief Propagandist. He disgraced himself at a gala song contest and experienced one of his régime’s own ‘camps’, but proved wily enough to be ‘rehabilitated’ and to be given he task of producing an official history of Laos. Sisane, as Kremmer expected, fed him the usual party line, but did say ‘confidently’ that the queen died before the king, a fact impossible to dispute in 1997, but which was, of course, just more poppycock.

Kremmer’s portrait of the last ruling king of Laos, Savang Vatthana, is poignant. A gentle and devout man more interested in his orchards than in the business of government, his political isolation perhaps allowed him to believe that ‘the superpowers would ensure that a balance of power prevailed in his strategically located country’. It was an impossible juggling act in a country divided into right, left and neutralist factions, divisions mirrored in the Lao royal family. In the 1960s Vatthana permitted the US to drop two million tons of explosives on guerrilla-held territory in the north-east, which had been invaded by the Vietnamese in 1954, the same year that Laos gained independence from the French. But nothing altered the bitter status quo until the Vientiane Accords of 1973, in which everyone agreed to a ceasefire and to ‘rigorously carry out the democratic liberties of the people’. Hindsight makes it clear that the Pathet Lao had no intention of honouring the agreement, and it is hard to believe that anyone thought they might. The king and his cousin, the prime minister, Souvanna Phouma, also leader of the neutralists (whose convictions probably tallied most closely with the spirit of the Accords), adopted a policy of appeasement that was sadly misguided, and when the US pulled out of Indochina, ‘the fate of Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia was sealed’.

Souphanouvong, the ‘Red Prince’, was the first president of that oxymoron, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic. A minor member of the royal family, he married a Vietnamese woman with similar ideas and together they ardently supported the communist struggle. He was evidently not inclined to show clemency to his cousin, Savang Vatthana. In 1977 Thammakhanty watched in despair as the guards delivered the king, his son and heir, Crown Prince Vongsavang, and Queen Khamphoui to Camp Number One. They were housed in a bamboo hut (hence the book’s title), and none of them withstood the deprivations for long. Three years later, the king was buried in an unmarked grave, two months after the death of his son. The unfortunate queen died in 1982.

Kremmer is a vivid writer, with plenty of similes to hand: the Mekong is the ‘ageless mother of the Lowland Lao’, which ‘suckles their farmlands’. The sombre tone of the book is often alleviated by memorable vignettes: of the lush landscape, crumbling wats, the extraordinary Plain of Jars (of which there is a snapshot), a rare performance by the former royal puppet troupe with their ornate wooden dolls. The festivals, architecture and rituals of Theravada Buddhism are also a bright counterpoint. The communists tried to proscribe the old religions, but faced too much resistance and gave up (a somewhat redeeming defeat). Laos has experienced an economic glasnost in recent years, with an increase in individual enterprise and tourism. Democracy, however, remains a long way off, and Khamphan Thammakhanty, now in his seventies, is unlikely to see his homeland again.

Comments powered by CComment