- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Reviews

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There is a wonderful sense of liberation in the title of this short novel: a sense of being able to gaze at a distant blue horizon and sniff salty sea air. It provides an exhilarating contrast with the atmosphere of claustrophobia suggested in Notes from Underground, Dostoevsky’s work of similar length and loosely comparable themes. But whereas the Underground Man rarely ventures into the street and never strays far from St Petersburg’s Nevsky Prospekt, the nameless protagonist of lgor Gelbach’s tale moves constantly between Leningrad, Moscow and Sukhumi. Sukhumi is a Georgian resort town on the Black Sea, where Rubin, a theatre director and friend of the dilettante narrator, owns a little-used apartment. Rubin prods our narrator to stay in it and enjoy the sun, the palm trees, the esplanade and the coffee, but also to write a novel about a certain theoretical physicist called Paul Ehrenfest. Ehrenfest was one of the circle surrounding Albert Einstein in the early years of the twentieth century when Einstein spent five years in St Petersburg. The narrator is not averse to the project, but even when he occupies the Sukhumi apartment, the muse remains elusive.

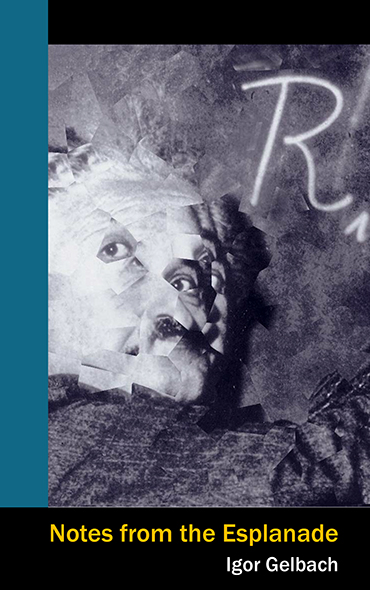

- Book 1 Title: Notes from the Esplanade

- Book 1 Biblio: Brandl & Schlesinger, $26.95pb, 192pp,

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Apart from the fact that Gelbach, though of Russian nationality, was born in Samarkand, a more fabled place than which it is hard to imagine, the Sukhumi pages of his novel sensuously convey that sense of the exotic, the remote and the beautiful that is part of everything the word ‘fabulous’ invokes. (His previous novel, Confessions of a Clay Man [2001], also set in Sukhumi but more consistently there, was so wonderfully poetical it was rather difficult to work out the story.) But nor is the notion of fable entirely inappropriate. The epigraph, for example, taken from a poem by Joseph Brodsky, reads: ‘Should you happen to be born in this empire / Life is better by the sea.’ So, despite the idyllic quality of the odd weeks spent in Sukhumi, this story is also set in the Moscow and the Leningrad of the Brezhnev era, known to all Russians as a period of stagnation, yet a time when the KGB and the threat of arrest were hardly less menacing than under Stalin. It could hardly have been a less fabulous epoch in which to live, although one anecdote that precedes the main action – or inaction – of the novel is certainly zany. Rubin has been involved in a plot to kill Stalin and to replace him with a Georgian actor (Stalin’s Russian was heavily accented) who would immediately smooth the way for Beria and his henchmen to move in, depose the false leader and take over the empire. Before this could happen, however, Stalin died of natural causes, and, soon after, Rubin follows him. Time, under Brezhnev stands still, and life indeed stagnates. The proposed novel never gets written.

But Gelbach’s novel, thankfully completed and fluently translated by Rae Mathew, conceals its own reference to fable, or at least to a certain adaptation of one of the greatest practitioners of the genre. It is not widely known that literature under the Tsarist regime suffered from a censorship that was no less oppressive than the more infamous crushing of individual and artistic freedom that operated under the Soviets. A poet could not write about the assassination of an ancient Roman emperor in case the word gave rise to subversive ideas. In this situation, both writers and readers learnt to exploit metaphor and subtexts that bypassed the censors, usually men of small intelligence, under the general umbrella of what was called Aesopian language.

Thus Turgenev’s heroes, who impotently flee the women who love them, are understood to be politically powerless men, unmanned by the draconian rule under which they live. The tradition continued throughout the Soviet period under the same name; and though Gelbach is writing in a time when subterfuge is unnecessary, his mesmerising story is designed to epitomise a society in which Aesopian language was sometimes the only way to escape to its more fabulous fringes.

Comments powered by CComment