- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

At one point in A War for Gentlemen, a school-teacher is reading Uncle Tom’s Cabin to her class in rural New South Wales in 1872. Seven-year-old Annie Fitzhenry excitedly announces that her father had fought for the North during the US Civil War. When the teacher subsequently visits Annie’s home, both she and the child are abruptly undeceived. Charles Fitzhenry is indeed a veteran of that war, but had served in the Confederate army.

Harriet Beecher Slowe forcefully argued that the disintegration of the families of slaves was perhaps the most pernicious aspect of slavery. In French’s novel, it is racial prejudice that separates parents, children and siblings – tragically, because entirely unnecessarily.

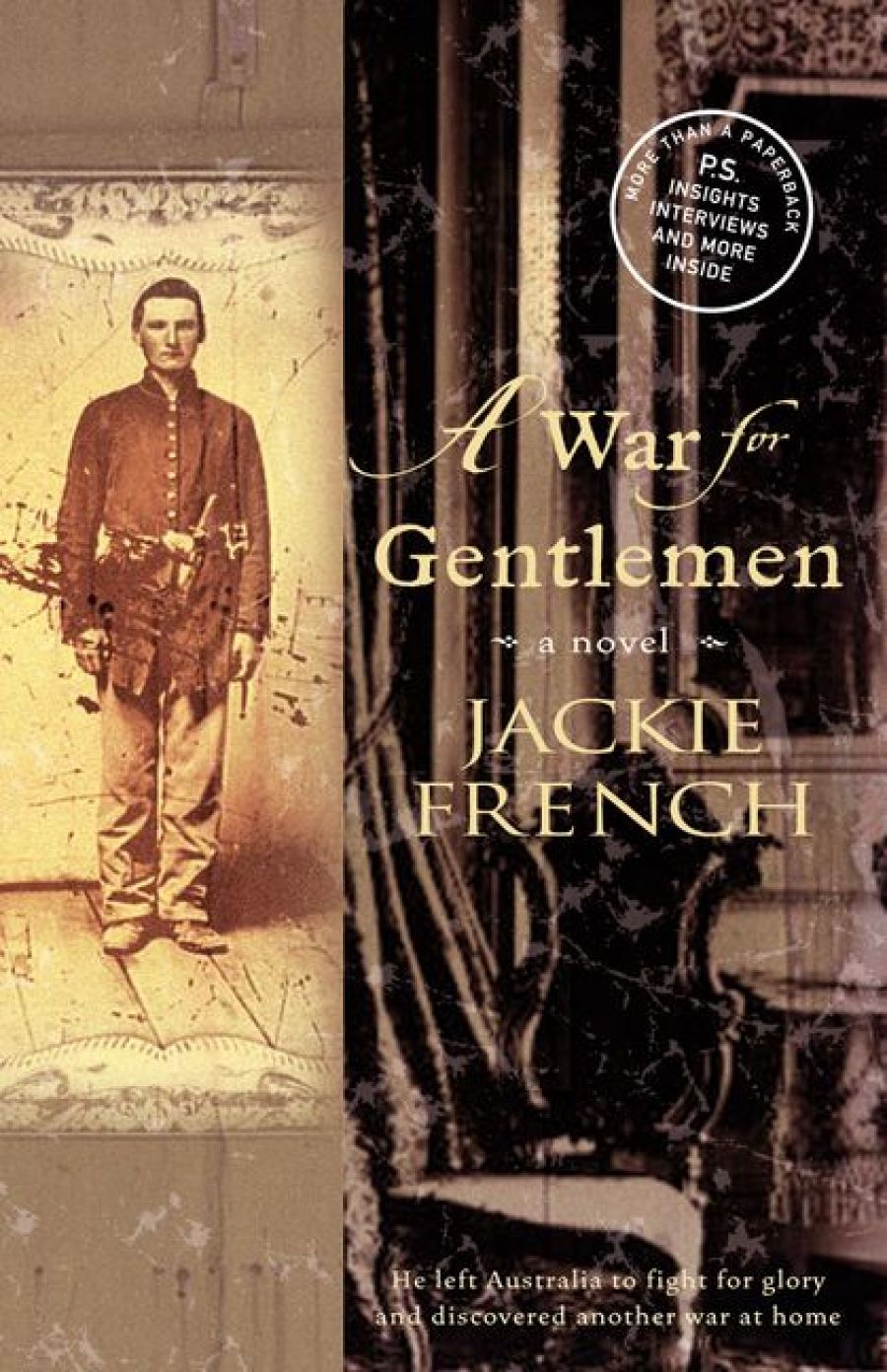

- Book 1 Title: A War for Gentlemen

- Book 1 Biblio: Flamingo, $29.95pb, 307pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

In an Author’s Note, French informs the reader that her novel is loosely based on fact – that there was ‘an Australian who fought for the Confederacy in the American Civil War; who deserted and escaped north with a woman who was a slave; who married her and was disowned by his family’. She makes it clear that she is not writing a history. since much about 1hose historical individuals is now untraceable, and asserts that ‘sometimes fiction can capture the essence of a story in the way that history cannot’. This is the conventional, often valid, claim of historical fiction, and A War for Gentlemen should to that extent be judged on its own terms. Nevertheless, I sometimes wished for an afterword in which French had briefly described her research and given some indication as to whether certain plausible elements of the book arc ‘true’. In interview, French has indicated that some of the descendants of the original Charles and Caroline arc still reluctant to reveal that an ancestor was an escaped AfricanAmerican slave. Perhaps this sensitivity – sad to contemplate in the twenty-first century – accounts for French’s discretion in relation to the ‘facts’.

After Charles is badly wounded in battle, a faithful slave takes him to a cousin’s home. One of Charles’s great-uncle’s slaves. the genteel, light-skinned Caroline, is left with the sole responsibility of nursing him. Caroline is in disfavour, having given birth to a black girl. The father of the baby had killed himself after failing in an attempt to run away. In a refreshing avoidance of romantic cliché, Charles docs not, at least at this stage, fall in love with Caroline. Rather, his decision to run away with her is motivated by his awareness that he cannot bear to return to fighting. He will remain physically and psychologically damaged for the remainder of his life. As a deserter, he knows that he will bring disgrace on himself and on his family. To salvage self-esteem, he seeks a different kind of romantic glory, as the chivalrous saviour of a woman in need.

It is a fateful decision. When he, Caroline and the child arrive in New South Wales, he writes to infom1 his parents of what he has done, having no illusions as to the consequence. His father disowns him, although he does provide a generous allowance, the sole income of Charles’s family for some time. French portrays the grieving parents sympathetically, as decent people constrained by the mores of their time. The villain of the novel is the lecherous great-uncle Duane who, unknown to Charles, is Caroline’s father.

In New South Wales, the isolated family is befriended by a neighbour, Mrs Merryweather, a salt-of-the-earth figure. As well as Caroline’s daughter, Susannah, and Annie, Charles and Caroline have a son. For some years, the family lives quietly with its secrets, but everything changes when one of the son’s boarding school classmates finds out that his mother is ‘a nigger’.

The focus of the Australian section of the book shifts largely to Annie, who is perhaps meant to represent hope for the future. but I would have liked more of Charles. Similarly, Caroline gradually develops as a character when she is abandoned. but she becomes disappointingly inscrutable again once her long-absent husband suddenly returns.

The narrative voice is a little uneven, but the novel as a whole succeeds as a moving and entertaining story. There is no ecstatic reconciliation scene to conclude this narrative. unlike the ending of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Rather, French leaves us with the poignant message that humans, being human. will continue to make terrible mistakes, and often for all the ‘right’ reasons .

Comments powered by CComment