- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

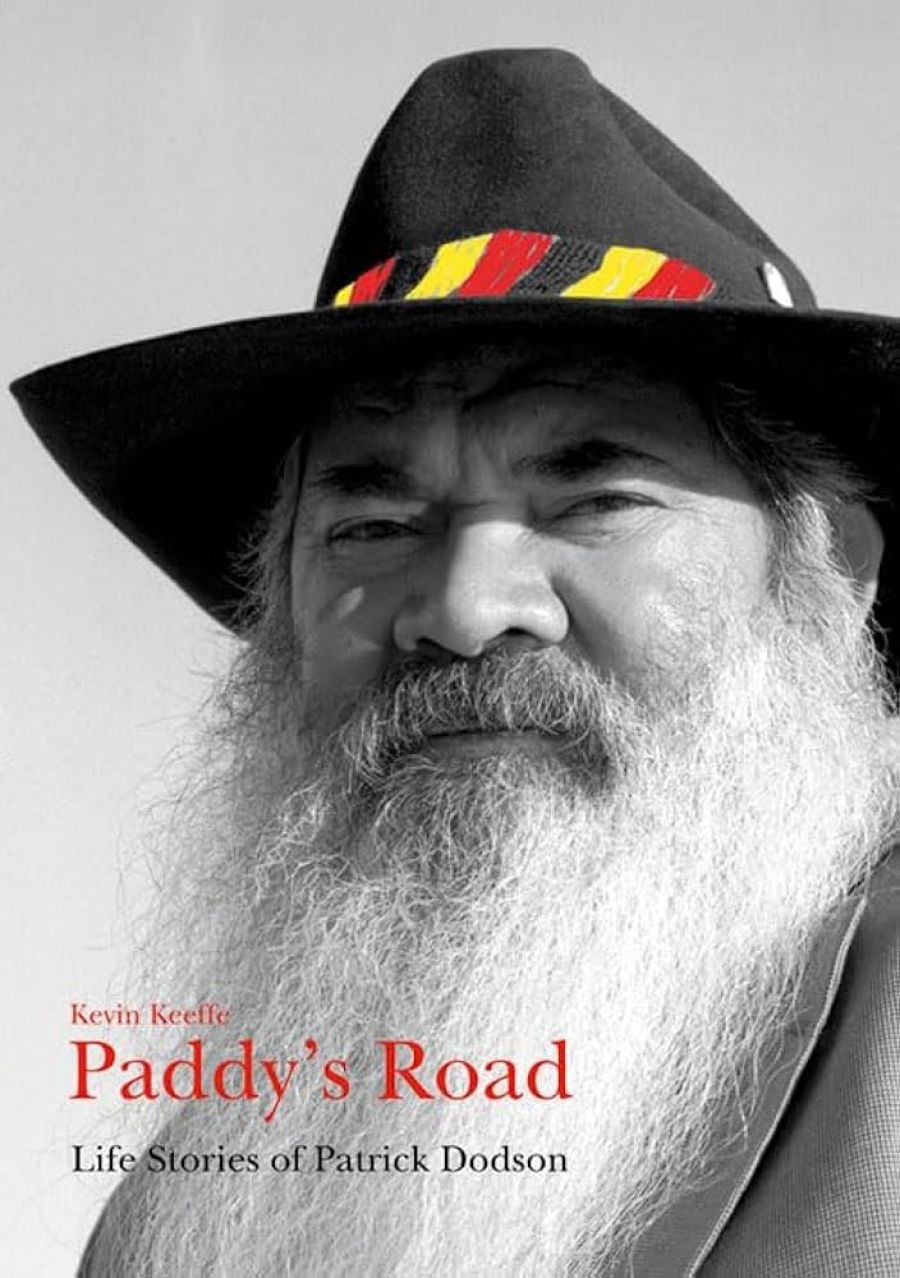

For many Australians, Patrick Dodson is the guy with the land rights hat and flowing beard. With Paddy‘s Road: Life Stories of Patrick Dodson, Kevin Keeffe ensures that Dodson will also be remembered for being the first Aboriginal priest and for his contributions to the reconciliation movement.

More a homage than a warts-and-all tale, Keeffe’s tome contains numerous feel-good and funny moments. For example, we learn that Dodson, the so-called ‘father of reconciliation’, was born in a laundry toilet, ‘nearly drowning in the Phenyl used for cleaning the ... pans’; and that Patrick’s grandfather, Paddy Djiagween, claimed his citizenship rights in person. - Book 1 Title: Paddy's Road

- Book 1 Subtitle: Life Stories of Patrick Dodson

- Book 1 Biblio: Aboriginal Studies Press, $49.95hb, 387pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

[When the queen visited in 1963] he shook the white-gloved hand and said to her ‘why can’t we have the same rights as the white man?’ The queen promptly agreed and indicated her wish that he be given full rights. My Grandfather went across to the Continental Hotel and demanded a beer. The barmaid was startled and refused, as the consumption of alcohol was forbidden to those without a dog tag of citizenship rights. An aide of the queen was summoned and confirmed the citizenship rights of the old man. He sipped his beer with a sense of gratitude – due more to the achievement than thirst I feel.

Such yarns about Dodson’s Irish and Aboriginal ancestors make for entertaining reading. The book is similarly enhanced by some great photos, including a magnificent shot of the twenty-seven-year-old Dodson taking a mark while playing Australian Rules.

The book is not always uplifting, however. We are told, for example, about Patrick’s Aboriginal grandmother’s fight to access her inheritance, kept from her by A.O. Neville under the guise of Aboriginal Protection; and about the sexual policing of liaisons between Aboriginal women and white or Asian men. Keeffe’s account of the interference that Patrick Dodson’s ‘rebellious’ mother had to put up with is particularly startling in this regard.

A few insider titbits also provide flashes of interest. For instance, in an interview, Keeffe encourages Dodson to reflect on the differences between working with Paul Keating and John Howard, the latter of whom Dodson describes as having an ‘assimilationist view’. Elsewhere, we discover that the English writer Bruce Chatwin gatecrashed a party to meet Dodson, whom he then fictionalised in his controversial book The Songlines (1987). Little touches, such as Keeffe’s clarifying headings and his use of a different font to document his own personal reflections, are also valuable.

Despite all these small strengths, however, Paddy’s Road has several flaws. For a start, the framework, in reflecting Keeffe’s prevailing interest in reconciliation, creates some problems. We first become aware of Keeffe’s slant in the acknowledgments, where his admiration for Dodson’s belief in reconciliation becomes apparent. Indeed, he presents his book as an answer to the question as to why Dodson maintains this belief. It is unsurprising that Paddy’s Road finishes with the author’s own reflections on the current stale of reconciliation, rather than with a focus on Dodson.

This focus on reconciliation is not a problem in itself. Biographies need cohering themes, and these are inevitably determined by the author’s own points of interest in his or her subject. Keeffe’s apparent resistance to historicising or critiquing the concept of reconciliation is, however, problematic. Moreover, by maintaining this focus, Keeffe seems to have unwittingly contributed to the public association of Dodson with the cooperative politics people tend to expect from Catholic priests. In light of Dodson’s break from the church, his resignation from the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation and his seemingly rather gruff persona, this soft lens seems inappropriate.

Keeffe’s interest in representing the ‘good’ Patrick Dodson also makes for some rather dull reading. The second half of the book, which moves away from detailing the Dodson family history and into an account of Dodson’s priestly and political life, lacks almost any reflection on the emotional and personal aspects of the ex-priest’s life. For instance, while we are told about Dodson’s tendency to drink heavily at times. Keeffe quickly moves on from any exploration of this, stating, instead, that Dodson condemned domestic violence. Similarly, although we learn that Dodson fathered a daughter as a young Aboriginal priest, there is no subsequent discussion of her place (or otherwise) in his life.

Keeffe’s refusal to provide readers with further details of Dodson’s personal life probably arises from his stated commitment to respecting ‘the [Dodson family’s] right to negotiate with me on how their story was to be shared’. While understandable and in a certain respect commendable, the author’s position has limited his capacity to write the best possible biography of this worthy subject.

Thus, the title of Keeffe’s book is apt. While we learn a lot about the road Patrick Dodson has travelled, the book provides few significant insights into the man himself.

Comments powered by CComment