- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In February 1974, Robert Rose, a twenty-two-year-old Australian Rules footballer and Victorian state cricketer, was involved in a car accident that left him quadriplegic for the remaining twenty-five years of his life. The tragedy received extensive press coverage and struck a chord with many in and beyond the Melbourne sporting community ...

- Book 1 Title: Rose Boys

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.95 hb, 289 pp, 1865086398

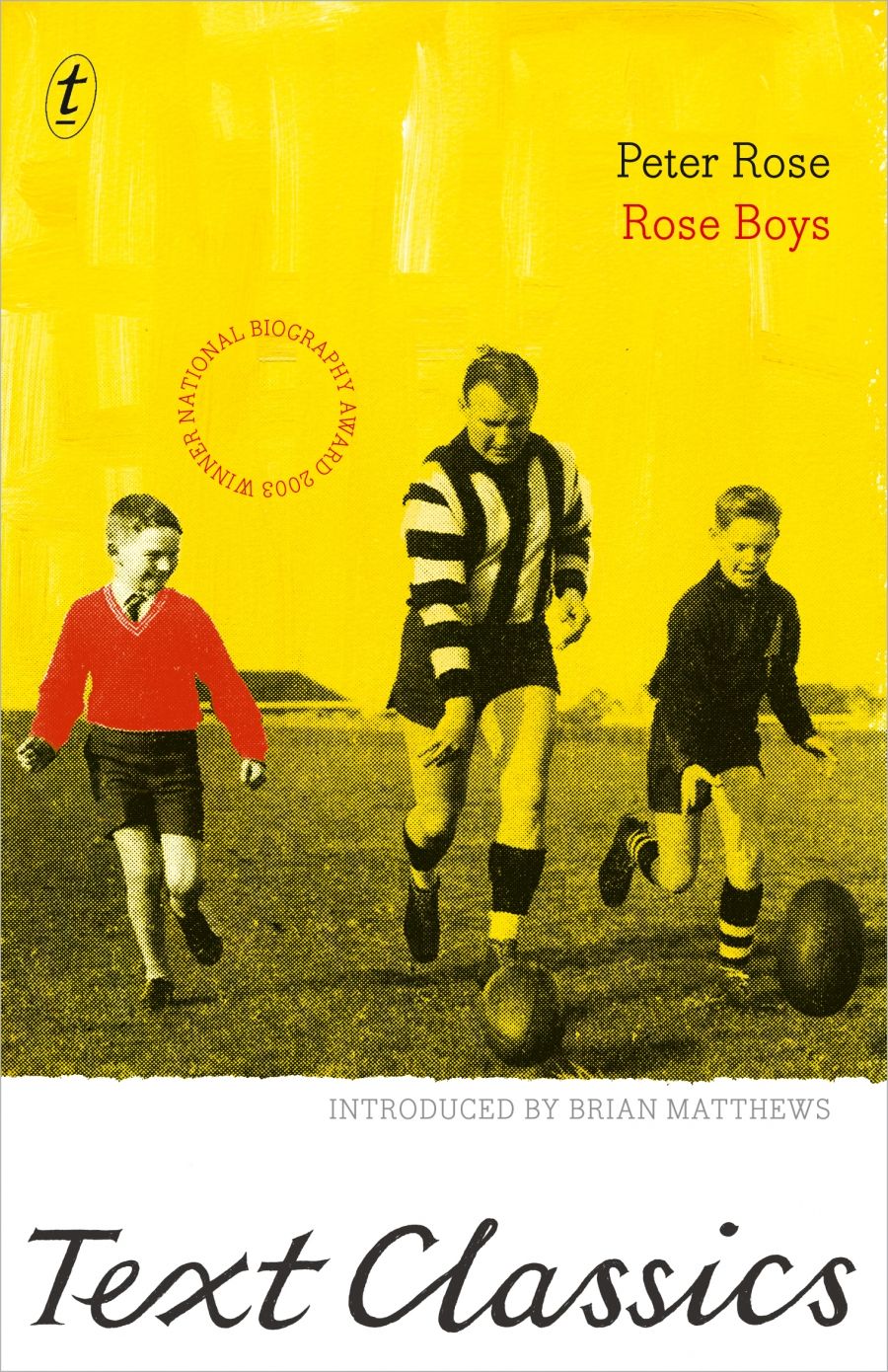

Bob Rose, the author, Robert Rose.

Bob Rose, the author, Robert Rose.

In writing the book, Peter sets out to ‘reanimate’ Robert; ‘to examine his achievement, what he symbolised, what he gave and what he withheld, what he divulged and what he never said, as a son, as a brother, as a husband, as a mate, above all as a tragic victim of that “second or two in time”’. Few books – if any – about Australian athletes can have been written at such a remove from the tired and unenquiring protocols of sporting hagiography. Though clearly loyal and deeply attached to his family, Peter, ‘a devotee of Henry James’s “temple of analysis”’, concedes that he must ‘violate old privacies’, disclose frailties and failings, in order to capture what is most important about this sporting life – not the deeds enshrined in family scrapbooks (‘those bibles of scrap, collages of self-delight’), but the moral and psychological quality of the life after the accident. And of the other lives that were touched by it. Here, as elsewhere, the book is eloquent, profoundly moving, deep-seeing into the mysteries of human suffering, adaptation, and connectedness.

Before the accident, Robert is the athlete as man’s man: attractive to, but inconsiderate with, women; laconic except when transformed by sport into a fierce and perfectionistic competitor; warmly attached to his mates. After the accident, he becomes a ‘formidable’ moral being. When his wife leaves him, Robert is at pains to soften the blow for his mother; when a few years later, in what must be one of life’s more excruciating examinations, his girlfriend falls guiltily in love with an able-bodied man, Robert’s response is: ‘“Don’t worry, it’s okay.”’ The book’s accounts of the ex-wife and former girlfriend are sympathetic: their departures are seen as symptomatic of the ways in which one person’s tragedy ripples out, often rendering proximate lives agonisingly complex. In a sense, this is what’s at issue in a scene late in Robert’s life when, desperately ill, he is tempted to refuse life-prolonging surgery in order to spare his parents further stress. They will have none of that, and Peter comments that this ‘ordeal of confidence had been cathartic. Everyone knew where they stood now. There were no limits. There had never been any limits, but Robert needed to hear it again.’

This is of a piece with an earlier description of the relationship between Robert and his parents upon whom, by now, he had become so massively dependent: ‘And all this time the bond between Robert and my parents was deepening … it was now prodigious, unqualified and profoundly tender. I found it awesome to watch.’ It’s awesome to read, too. This is a book about the nature, and ultimately the limitlessness, of love. The parents emerge as fine – though by no means flawless – people: the mother, Elsie, empathetic, loving, and steady in her devotion to Robert; Bob, a man famed for his toughness on the football field, also devoted, attentive, tender – tender, indeed, in a way that moved this reviewer and football follower to rethink some of his assumptions about footballers. These ‘highly civilised parents’ don’t mind that Peter isn’t an athlete; indeed they embrace his literary career and give him, an often tortured soul among ‘sunny’ family people, what he needs to become a different kind of Rose boy. Crucially, he’s able to identify closely with the artistic and reflective Elsie, but without forfeiting Bob’s approval. Australian men’s autobiography has given us a veritable rogues’ gallery of inadequate, absent, or destructive fathers: Patrick White, David Malouf, Manning Clark, George Johnston, the Wherrett Brothers, Morris Lurie – the list goes on. Such figures confirm grim assessments of masculinity in Australia – its styles, the modes of relatedness it allows, its patterns of reproduction. But in the autobiographies of writers such as Brian Matthews, Raimond Gaita. and Arnold Zable, another story emerges: here, father–son relationships are loving, tender, nurturing, emotionally warm. These stories, too, need to be told. Rose Boys, with its affectionate and admiring, but also probing and sometimes bemused, portrait of Bob, belongs in this tradition.

Its account of male relationships goes well beyond the father–son configuration. Peter writes openly about his sexuality and about three key gay relationships in his life. This aspect of the story is well handled: without exceeding the needs of the larger narrative, it provides essential contexts for understanding Peter’s speaking position, his emergence as a gay poet and family chronicler from a footballing dynasty, and, above all, his relationship with Robert. As Peter puts it: ‘Brothers so close yet so incongruous meet improbably in this shifting text.’ The sibling relationship is many-layered: typically boyish (nothwithstanding Peter’s brooding sensitivity) before the accident; increasingly tender, intimate, after it. The book begins with an account of a florid dream involving Robert that Peter has some time after the accident. Its penultimate chapter ends with that dream transmuted – after many drafts – into poetry. The poem is searing, Dantesque, and is entitled ‘I Recognise My Brother in a Dream’. The last two lines are: ‘Only then, as in a paradisic dream, / do I recognise my young guide as my brother.’

In a sense, Rose Boys is just this: an anguished and elaborated narrative act of recognition – recognition in the sense that a brother takes account, in the deepest ways his very considerable loving moral imagination can manage, of the human being that was the other Rose boy: so incongruous, yet so close.

Robert dies an appalling death after much suffering. But there is still one ghastly twist to come. Peter, Bob, and Kevin Rose have to perform a grotesque penultimate rite. Of the sight of Robert’s sheet-draped body, Peter writes: ‘I remembered the wounds beneath the sheet. Ecce homo. What had they done to him?’ Few works of life-writing – perhaps not even Nietzsche’s – can sustain the weight of such a line. But Rose Boys can, so powerful is its evocation of Robert’s suffering, his moral stature, and the wider implications of his life.

It’s at this moment that a sense of recognition sweeps over Peter: ‘Finally, with a pang of something that would never fully dissipate – incompletion, incomprehension, rich regret – I recognised my brother.’

Life-writing, one might say, is ultimately about recognition. Rose Boys is life-writing of a very high order – a special book about a special man and the diminished life he managed so richly to share with others.

Comments powered by CComment