- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Memoir from a Vanished Sydney Sky

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

How to shape the fiction of one’s life? There is something to be said for the no-nonsense narrative thrust of Errol Flynn in kicking off My Wicked, Wicked Ways, one of the most readable and also self-consciously ‘literary’ of all showbiz autobiographies. ‘Detesting’ books that begin after the fashion of ‘there was joy and happiness in the quaint Tasmanian home of Professor Flynn when the first bellowings of lusty little Errol were heard’, the actor-autobiographer gets straight to what he archly calls ‘the meat of the matter’: his tumultuous film career and the associated carnal exploits that constituted his notoriety.

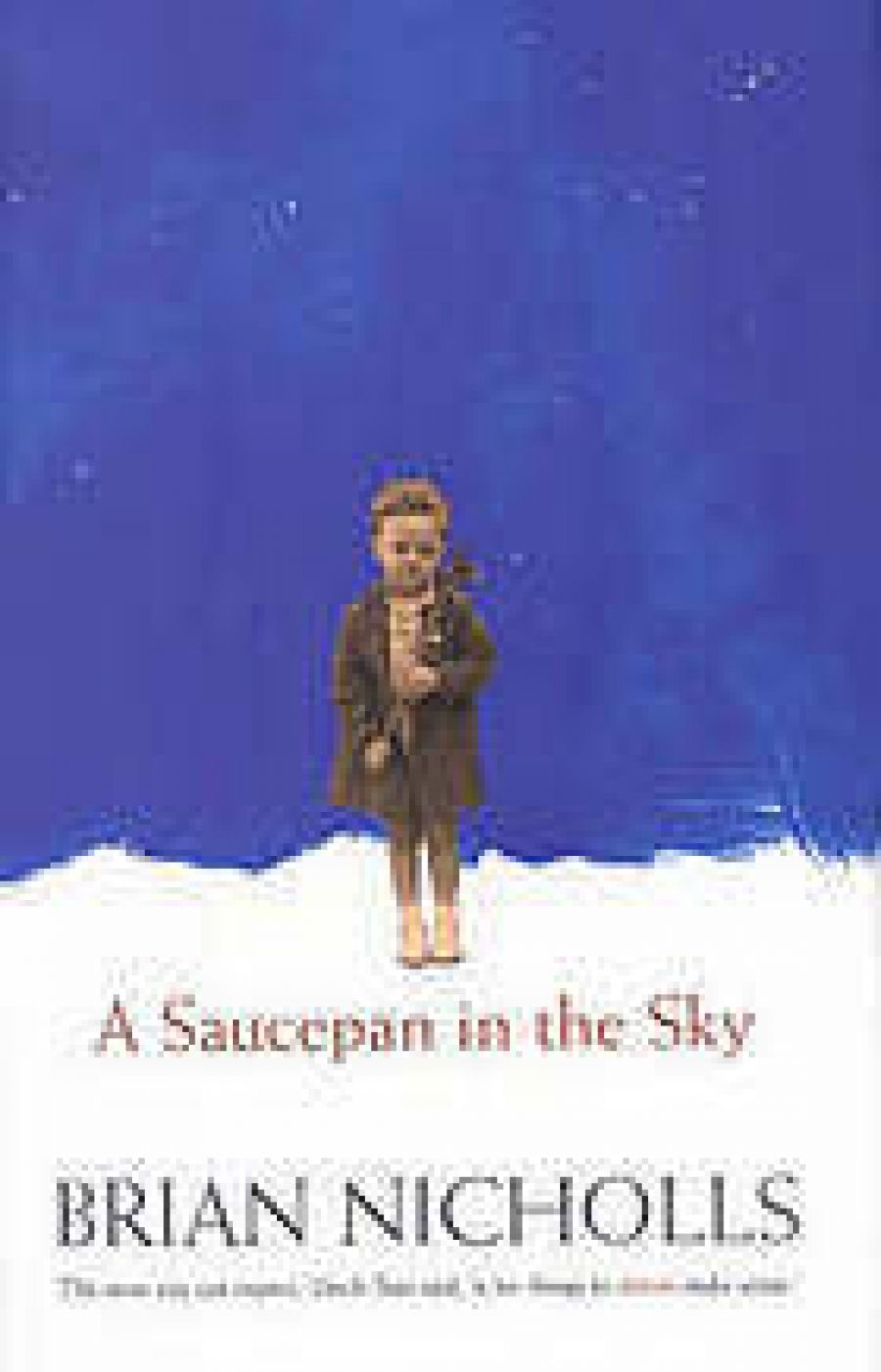

- Book 1 Title: A Saucepan in the Sky

- Book 1 Biblio: Hale & Iremonger, $29.95hb, 184pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Flynn, of course, had a ready audience. The Sydney-born Brian Nicholls, sometime film editor for the BBC and later an ABC television producer, has a tougher task. His auto-biographical A Saucepan in the Sky begins unpromisingly: ‘In 1938 Australia had a population of 6,935,909. I was one of them.’ Yet the self-dismissiveness with which Nicholls buries himself in this statistic is ironic, for this is one of those modest autobiographies which – it is hard to avoid the clichés – reveals the exceptional in the humdrum and the uniqueness of so-called ‘average’ life.

The inner-urban, working-class milieu has provided the context for some of Australia’s finest autobiographical storytelling, as Brian Matthews’s recent, luminous St Kilda memoir A Fine and Private Place attests. A recreation of Nicholls’s early childhood in Petersham in Sydney’s inner-west, A Saucepan in the Sky is narrated from the growing child’s perspective. This is a hard narrative act to pull off. Sometimes the wide-eyed child’s gaze doesn’t quite work. ‘What happened next in the world,’ Nicholls writes, ‘was that one day a war started. Germany wanted lots of other countries and then the Japanese decided they wanted our place, Australia, as well as their own. Dad had to go New Guinea to tell the Japanese to go home.’ Presumably, Nicholls is recycling the historical fairy tale told him by his parents to explain his father’s prolonged absence, but the adult reader is apt to lose patience with a kind of literary play school. Midnight’s Children this isn’t.

Generally, however, the child’s perspective gives us a sense of the wonder and puzzlement of growing up, and the challenge of negotiating the promiscuous domesticity of working-class life. The Nicholls ménage located in the old Petersham terrace with ‘a wrought-iron balcony’ (shades of Hal Porter’s Watcher) includes, in the front room, Mum and Dad (when he’s not off telling the Japs to get lost), his grandmother and her de facto, the wonderfully disreputable Uncle Stan, who inhabit the middle bedroom, and Uncles Vick and Doug in the back bedroom. Great Uncle Dick sleeps downstairs in the lounge room behind a makeshift partition, while the young author and his little brother sleep on that front balcony overlooking the street. For a time, a swaggie inhabits the backyard washhouse, and there’s a cocky living in a converted ice-chest.

This is a Sydney that has largely vanished. There’s neither a non-Anglo-Celt nor a discarded needle (‘the grog’ being the resident social demon) in sight. A Saucepan in the Sky describes a social landscape marked by ‘so many sick men’, the human debris of the late war; and, on the domestic front, a household presided over by Nicholls’s stoical mother, as tender a maternal portrait as you will ever read. Out the back, Uncle Stan is perched in the dunny every Saturday morning, trousers around his ankles and braces on the floor, a half-smoked roll-yer-own behind his left ear and pencil stub in his right hand, doing the racing form. It was a time when adults reproved kids with the terrifying words ‘you’re in more strife than Ned Kelly’ and a kid’s global vision, before television, let alone the Internet, contracted to a view of the Parramatta Road as ‘the busiest and most dangerous road in the world’. As I said, a lost world.

Described as ‘that bunch of odd angels who watched over me’, Nicholls’s motley collection of ‘Uncles’ are especially well drawn. Uncle Stan is full of gnomic utterances. ‘Keep away from cemeteries,’ he warns the author. And then there’s Uncle Vic, a war veteran with chest problems, a bootmaker in working hours and ace ballroom-dancer outside of them. Vic is a ‘funny bugger’ with a Conradian outlook. ‘Civilisation is only a few inches thick,’ he advises his nephew. ‘It’s about as deep as the asphalt on the road. Underneath it’s just earth. It’s the jungle. Like it’s always been. People are just savages in suits.’

A Saucepan in the Sky is bereft of cynicism, retrospective pain or complaint – an utterly readable account of a happy childhood in a memorable, ‘ordinary’ environment. A charming book.

Comments powered by CComment