- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Quotation marks around the big subject

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

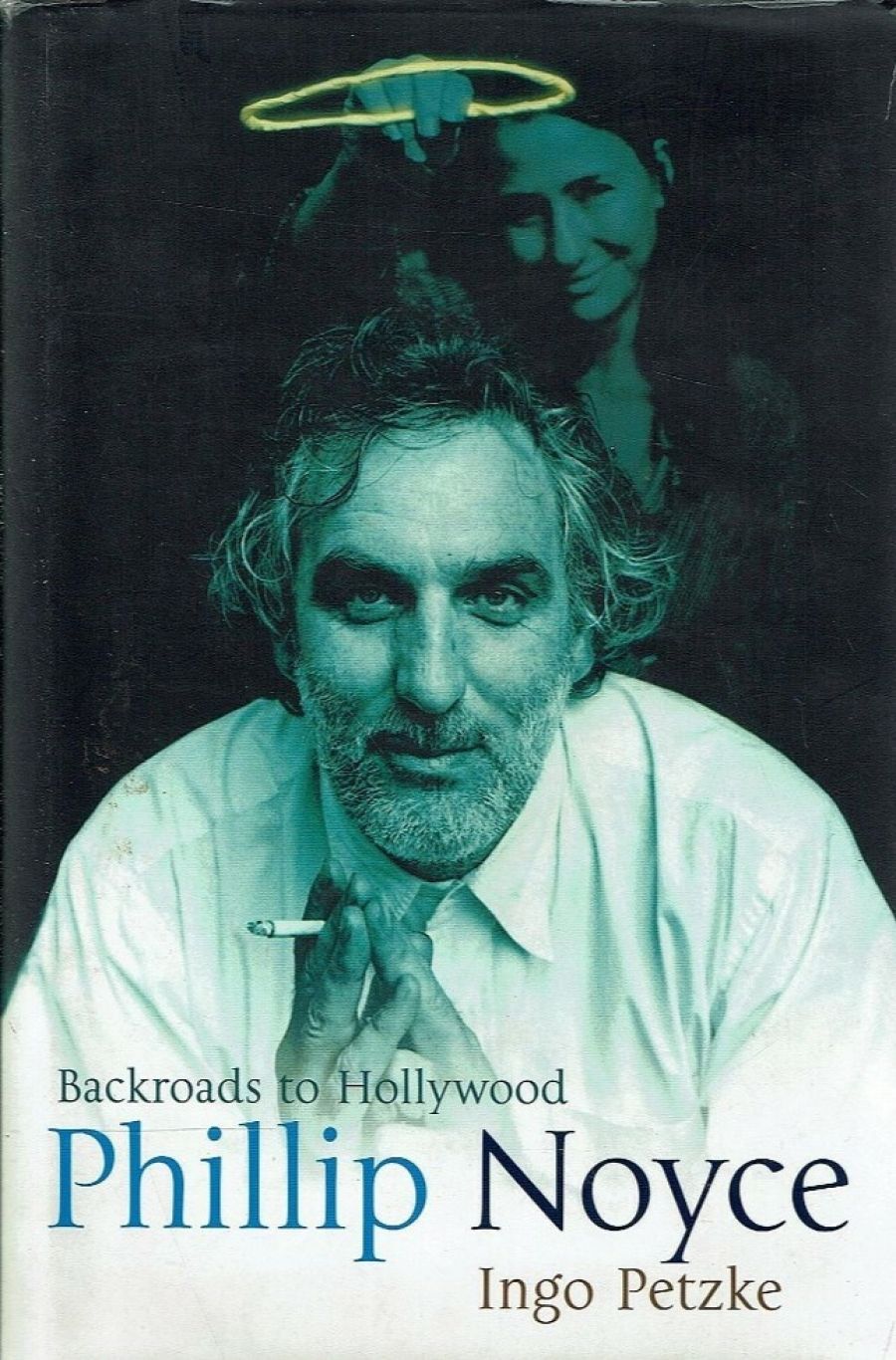

To start at the beginning (that is, the dust jacket): giving the author’s name as Ingo Petzke is a misnomer. It suggests that he has written a biography of the Australian film-maker Phillip Noyce, when in fact this is neither biography nor autobiography. This indecision about its mode undermines its value. I’ll return to this.

- Book 1 Title: Phillip Noyce

- Book 1 Subtitle: Backroads to Hollywood

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan, $45 hb, 402 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

As everyone knows, the Australian film industry experienced an exhilarating revival in the 1970s. While a few of those film-makers who helped to bring this about, including Tim Burstall (director of Stork, 1971), remained essentially Australian film-makers, most of the notable directors went on to international careers of varying degrees of distinction. Peter Weir had several major Hollywood successes, most recently Master and Commander (2003); Bruce Beresford’s Driving Miss Daisy (1989) won a Best Film Oscar; Gillian Armstrong made a luminous version of Little Women (1994); and Fred Schepisi’s US output included a stylish espionage thriller, The Russia House (1990). Without these four names – and that of Phillip Noyce – there would scarcely have been a revival.

Off, then, they all went, though most would return to make the odd Australian film. Noyce is interesting as a symptomatic case: he made one of the most attractive of all 1970s Australian films, Newsfront (1978), left for Hollywood a decade later, and returned roughly a further decade on to make one of his most heartfelt films, Rabbit-Proof Fence (2002). At present, his Australian films seem like the quotation marks around the major statement – that is, his American films, though generally they are big jobs that made him bankable rather than critically acclaimed. Like his 1970s peers, his Australian films tend to be smaller, more personal works, and that is perhaps as much a symptom of the different production context in which they all found themselves in the US as of individual proclivities.

The interest of this book ought then to lie partly in Noyce’s singularity, partly in his typicality, but in fact it does justice to neither possibility. As I said at the outset, Petzke is scarcely the ‘author’ of this book in the commonly accepted sense of the word. What he has done is to thread together large chunks of oral testimony, letting these stand as often as not without comment or with no more gloss than, say, ‘Marc Neufield (or whoever) remembers this slightly differently’, but not feeling bound to pursue investigations further.

Now there is nothing intrinsically wrong with oral testimony as a source, as Kevin Brownlow’s magisterial biography of David Lean (1977) made abundantly clear. The difference is that Brownlow was in charge, reflecting on and assessing what he was told. Petzke simply has no purchase on his findings, so that a good deal of his extensive interview material goes for little. As well, too much of what his respondents have to say sounds like the puff one finds in the ‘production notes’ put out by distributors, about someone who was ‘wonderful to work with’ and how actors were turned on by their roles. In relation to the latter, even a great screen actor such as Michael Caine, who played Fowler in Noyce’s fine version of The Quiet American (2003), can deliver profundities like this: ‘What attracted me to play Thomas Fowler was that it’s one of the greatest parts you could get. There’s every emotion from A to Z and back again, and he’s not only a very deep character, he’s a very wide character.’

And so on. There’s no reason why actors need to be articulate about what they think they are doing in a certain role – it’s their job to act, not to pontificate; it’s a serious author’s job, though, to make use of what such people tell him. In this case, it would have been better for Petzke to embark on a major critical biography of Noyce – he has plenty of source material for the job – or to encourage Noyce to tell his own story. What we get here is neither one nor the other; there are slabs of sometimes instructive contributions by Noyce himself, interspersed with the comments of his collaborators and, towards the end of each chapter on a particular film, a round-up of (mainly awful) reviewer pap.

The oral commentary includes some fascinating trivia, such as how Sharon Stone (elsewhere described as ‘an icon’ – of what?) bit William Baldwin’s tongue in a love scene in Sliver because she didn’t like working with a ‘boy’ like him and would have preferred his brother Alec, a ‘man’, whom ‘I’d let … throw me over the table anytime’. Goodness. If this sort of thing fascinates you, then you may find some of the background stuff to your taste. Some of it is undeniably entertaining, as is the insight into the often appalling workings of the Hollywood factory.

However, even when we are offered, chiefly through Noyce’s own words, insight into the tribulations of location filming in, for instance, Bogota or, perilously, in Moscow, it’s hard to resist the seditious thought: was it all worth the trouble and danger for a string of empty-headed action flicks? In the case of The Saint (1997), filmed in Moscow, it seems downright foolhardy if not indeed irresponsible to have allowed his Russian adviser, Tatiana Petrenko, and her husband (they had two young children) to risk their lives in the interests of filming a huge communist rally in Pushkin Square, with subversive banners. ‘Sometimes it was very scary, because Phillip is fearless,’ she says – and all this for a ridiculous film starring the absurd-sounding Val Kilmer.

Noyce is astute about the differences in setting up modest-budget films in Australia as compared with wildly expensive Hollywood blockbusters. The accounts of his Australian films evoke vividly a key period in the resurgence of the local industry, though it may be that he drifts into cliché about matters such as the landscape and how ‘being on the road’ is ‘perhaps [the] most Australian of concepts of the self’. He makes the world of Hollywood deals sound unbearable, as if you should only put yourself through it if you knew you were going to make Citizen Kane – or at least The Sound of Music. And yet he survived half a dozen such ordeals, even if, sadly, the films hardly seemed worth the trouble.

It’s hard to tell what kind of writer Petzke is, but he certainly lets stand some awful junk from his interviewees, who might have expected – and would certainly have benefited from – judicious editing. Where Petzke himself emerges, he reveals a penchant for coy phrases such as ‘palate-tickling encounters with wine’ and suspect formulations such as this on Noyce: ‘A suave A-league citizen of planet Hollywood who domestically acts as a voice in the wilderness.’ I think it’s hard to take seriously someone who writes like this.

Those who value Noyce’s Australian films – especially Newsfront, which, in persuasively integrated fashion, chronicles key formative aspects of the country’s recent past, or, not to limit him to the socially significant, the taut thriller Dead Calm (1989) – will find his story worth telling. The best one can hope of the present volume is that someone will use it as a resource for doing the job properly.

Comments powered by CComment