- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Sport

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Consumed by the game

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Albert Thurgood, whose first season playing for Essendon in 1892 was described by the Leader as ‘in every way phenomenal’, was simply the ‘Brighton junior Thurgood’ when Essendon selected him for the first game of that season, though his all-round athletic prowess at Brighton Grammar School had already marked him as a possible ‘prize’ recruit. Though St Kilda was his nearest club, and though, as Lionel Frost recounts, St Kilda actually selected him for a game in 1891 ‘in the hope that he would join them’, he opted for Essendon, a decision which moved several other clubs to wonder if Essendon had organised a financial inducement. Plus ça change.

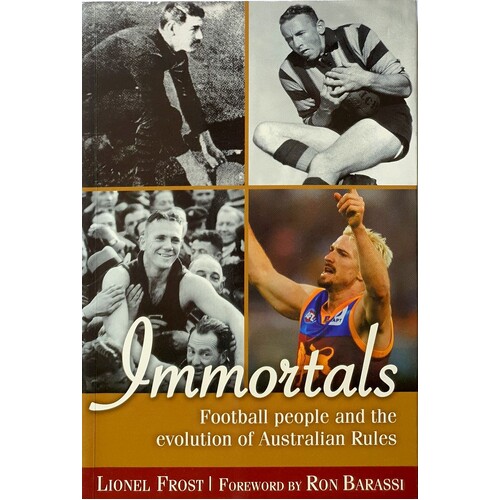

- Book 1 Title: Immortals

- Book 1 Subtitle: Football people and the evolution of Australian rules

- Book 1 Biblio: John Wiley & Sons, $34.95 pb, 312 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: Keeping the Faith

- Book 2 Subtitle: Collingwood ... the pleasure, the pain, the whole damned thing

- Book 2 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $22.95 pb, 276 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Immortals is full of such piquant, revealing or quirky moments, especially where Frost deals with the early manifestations of Australian Rules football and its founding fathers and ground-breaking coaches. There is Phil Matson, for instance, whom West Australians saw as ‘the prince of coaches’. He was the first to place systematic emphasis on basic skills of marking and kicking, and to insist on hard, disciplined training. Skill and precision allowed his teams to adopt a mode of play-on football that involved passing the ball instead of kicking high and blind and placing a premium on players ‘finding space’, as we would say today. All very familiar, except that Matson was developing these ideas in the early years of last century. His emphasis on discipline did not extend to his own behaviour, however, reversing the twenty-first century paradigm of well-behaved coaches and players out of control off the field. Matson was a significant drinker, a gambler who won and lost big, and a larrikin; but he had a brilliant football brain – not to mention his class as a player – and when he died in a road accident, aged forty-four, the loss to football was incalculable.

Frost sensibly doesn’t spend much time in detailed justification of his choice of these ‘immortals’. These are people who, in Frost’s opinion, had a lasting influence on the game’s evolution; and, more interesting still, the nature of whose careers enables us to understand ‘what it was like to be involved with football in changing times’. This latter claim is a large and intriguing one, and potentially difficult to flesh out, but Frost does so splendidly, with, for example, the Collier brothers, who ‘lived out their boyhood dreams by winning places in the local team that they loved, and became key players and leaders in one of the greatest teams of all time’; Jack Oatey, who said of the great Sturt Football Club Captain, Paul Bagshaw, that he ‘could drop kick a pea up a fowl’s bottom from 70 yards, and not ruffle a feather’ and who once reflected that ‘whatever [tactic] you can think of, someone else has tried it before … but couldn’t make it work’; and Tim Watson, who reflected as he contemplated the last few years of his football life, that ‘from 15 to 22 football consumed me and there was a time when I thought “Crikey” I can’t remember being 15, 16, 17 or 18 because I never did anything other kids that age did’.

As these brief quotations help to suggest, Frost has the anecdotalist’s eye for the telling moment or phrase or incident. There is also, however, an empathetic quality, a compassion, in how he goes about his biographies, so that their central focus – Australian football and its growth in various hands – is never allowed to become a dehumanising or merely technical component. It is the people (whether immortal or not can be argued about) who give his story its impetus and attraction and who enable the game to be seen from a slightly different direction – not solely historical, not merely sports history, not only the chronology of tactics.

The prose can be a bit stolid at times, and the method – introduction, biographical details merging into early career etc. – drops into a predictable pattern. And while I have scrupulously not wasted anyone’s time arguing about his selection of ‘immortals’ (you can detect his personal sympathies and interests here and there, but why not), I think the choice of Akermanis – brilliant, flamboyant, eccentric, sui generis – looks like a concession to flair and colour, if not also to the recently all-conquering Lions. Andrew McLeod, Chris Judd, Warren Tredrea spring to mind, all of them examples of prodigious interstate talent without the penumbra of self-indulgent celebrity.

In his preface, Frost remarks that ‘a focus on events that happen on the field, or the broad issues that affect the way a club is organised’ will not allow for concentration on the ‘human face’ of the game. With some adjustment, this is a criticism that might be applied to week-by-week football narratives, the story of a season with a particular club. In Australia, Martin Flanagan’s Southern Sky, Western Oval (1994) is one of the models of the genre; in Europe, Tim Parks’s A Season with Verona (2003). Steve Strevens, author of Bob Rose: A Dignified Life (2003), joins this line with his Keeping the Faith: Collingwood … the Pleasure, the Pain, the Whole Damned Thing. Strevens writes well on sport, and there is much to admire in his painful journey through one of Collingwood’s more forgettable seasons.

The trouble with Keeping the Faith – and other books of this genre – is that it won’t pass the ‘so what?’ test. This is not Strevens’s fault. He has wit, descriptive capacity and an appealing, plain style to bring to his story. And he recognises the virtue of variation. He does not proceed doggedly from match to match but intersperses anecdote, memoir and observation. But the whole enterprise depends on one’s acceptance that Collingwood is ipso facto special and more important than any other club in the competition; and that it is so because, well, it always has been – or, really was once, perhaps fifty years ago. Strevens’s laments could be echoed by any true believer waving any of the fifteen other flags, all of whom are keeping a faith just as aflame as Strevens’s. Convinced as he is of Collingwood’s superiority, even he can’t help sounding exclusive in that way that Collingwood was once able to be but no longer is: ‘it must be difficult to front up each year and put up with what the Saints dish up most seasons,’ he observes – a remark roughly equivalent to Jack Elliot’s ‘tragic history’ jibe.

But, needless to say, Collingwood supporters will love it – some pleasure, much pain and certainly the whole damned, unravelling, disastrous season.

Comments powered by CComment