- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Children's and Young Adult Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Reading a handful of primary-school-age historical novels in swift succession underlines the commonality of stratagems for encouraging young readers to engage with the past. First, there is the need to find a credible child role to focus on. Then, since adventure in historical times fell largely to the lot of boys, a female interest has to be introduced, or, with some contrivance and loss of credibility, the main role handed over to a girl in disguise.

- Book 1 Title: The Astrolabe

- Book 1 Subtitle: Adventure in the southern seas

- Book 1 Biblio: Lothian, $14.95 pb, 176 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

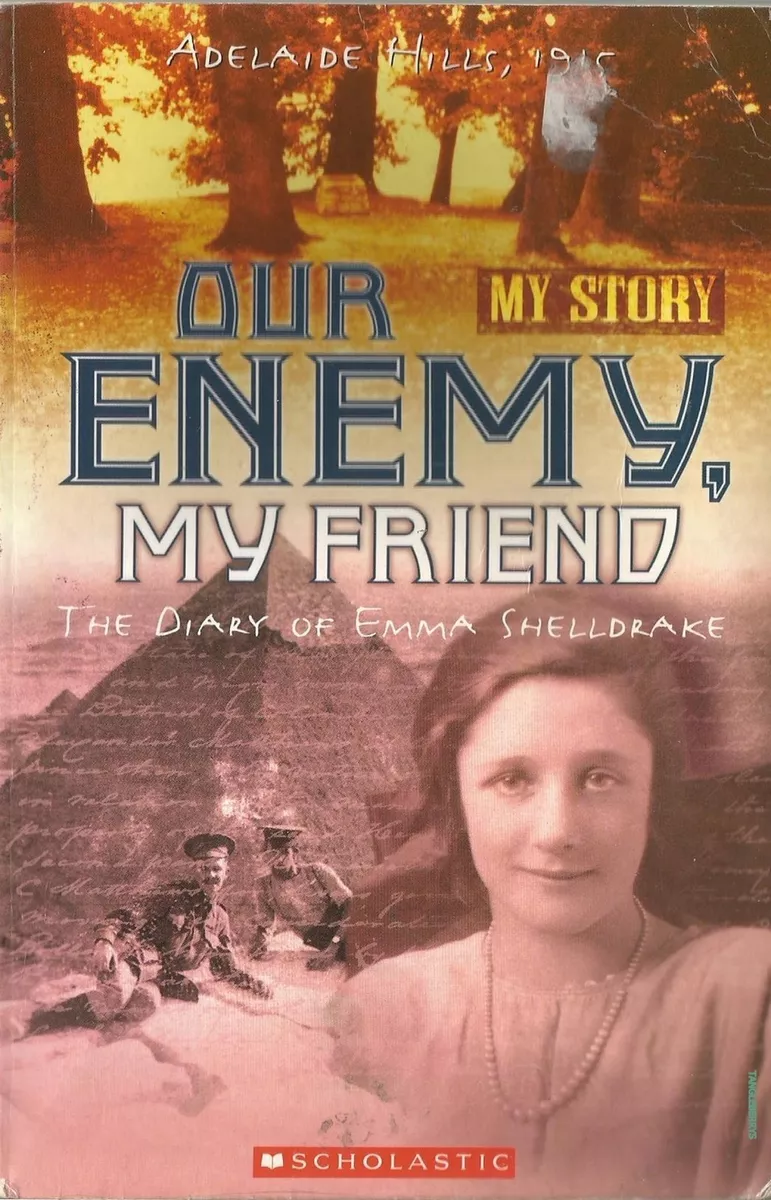

- Book 2 Title: Our Enemy, My Friend

- Book 2 Subtitle: My story

- Book 2 Biblio: Scholastic, $16.95 pb, 169 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

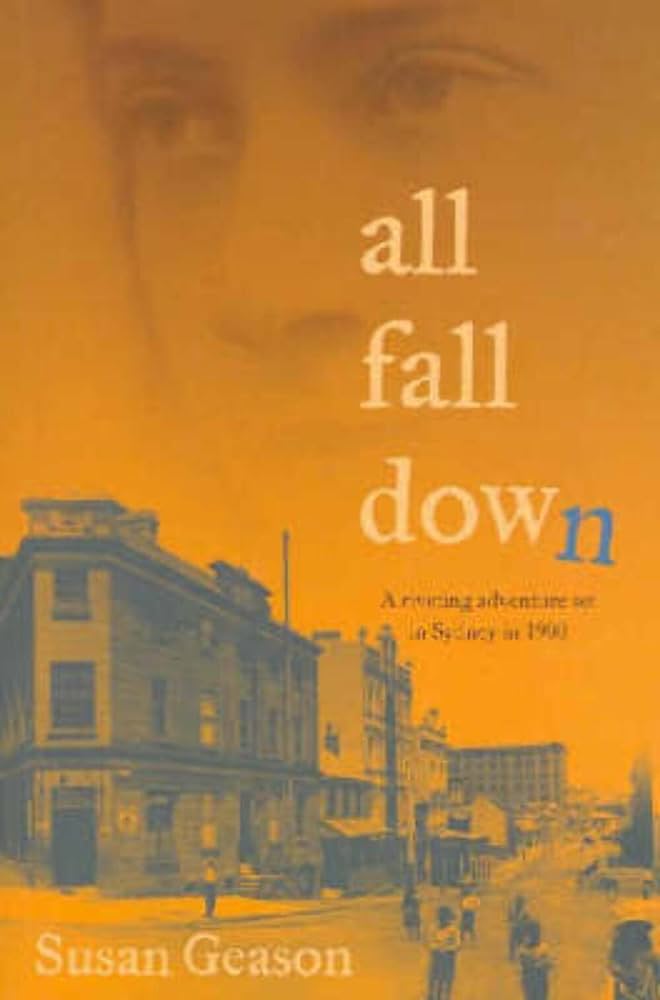

- Book 3 Title: All Fall Down

- Book 3 Biblio: Little Hare, $14.95 pb, 134 pp

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

Susan Geason takes the latter course in her first foray into fiction for younger readers (All Fall Down, Little Hare, $14.95 pb, 134 pp). Set in 1900, in Sydney’s notorious Rocks area, it is a lively source of information on women’s suffrage, the Salvation Army, slum housing, white slavery, Chinese gambling dens and the bubonic plague. Christabel McManus, its inevitably feisty heroine, is a bored fourteen-year-old heiress. Her newly widowed doctor father consigns her largely to the care of a governess and servants, when he isn’t discoursing on the symptoms of cholera and the plague.

The plight of one of the household’s maids, Maggie, leads Christabel to think for the first time about the hidden lives of servants. Getting Maggie’s young son back from his larrikin father, who has snatched the boy in order to initiate him into a life of crime, becomes an all-consuming project for the teenager, and an antidote to the discovery that her father is showing signs of interest in an elegant and eligible new arrival in town. Borrowing boys’ clothes and deepening her voice, Christabel heads off into The Rocks to rescue a surprised and reluctant Paddy.

This novel is rather more contrived and didactic than the entertaining Syd Fish thrillers that Geason writes for adults, and the reader often must strain to suspend disbelief. Author and heroine alike put more faith than seems feasible in the power of a cap to cling to tell-tale pinned-up braids, particularly when their owner is being lugged about under a brawny arm. As to why Christabel’s relative refinement, particularly in terms of accent, never arouses the suspicions of a series of underworld characters, that is a mystery greater than any the plot can provide. Occasional confusion over the names of two young male protagonists is presumably due to poor proofreading, but it nevertheless hints at a lack of definition among important minor characters.

Wendy Macdonald’s Castaway Convict (Cygnet, $16.95 pb, 152 pp) is a ridgy-didge boy, but he suffers from amnesia and is once revived with smelling salts by his patrician female sidekick. A fast-moving plot that twists and turns right to the end pits youthful virtue against unprovoked adult vice and greed. It is a wintry 1845, and Josh Martin finds himself an inmate at Point Puer, the notorious boys’ section of Port Arthur. Answering reluctantly to the unfamiliar name of ‘Tom Parish’, he cannot remember anything before his present confinement, nor what he might have done to earn it, and finds himself a dunce at the circular games of pocket-picking with which his companions apparently entertain themselves. An ill-natured shove into the icy southern seas unexpectedly results not in death but in the freedom of the bush – a world with its own horrors, including another pair of plotting and unprincipled adults, but which eventually delivers him to people who treat him fairly, including twelve-year-old Sarah, who becomes both his champion and benevolent martinet. Sarah orders Josh to remember, and remember he does, fleshing out the enigmatic prologue with which the book begins as sights, sounds, images and encounters around Hobart trigger memories of a painful recent past.

All is not yet plain sailing, however: Josh is returned to Point Puer, where he typically improves the shining hour by teaching his fellow prisoners to read, until his memories are dramatically confirmed by a deathbed confession. Even now, there are further turns of fortune as the loose ends of the story are neatly gathered in, but we are never forced to doubt that justice will be done or that Sarah’s cunning and Josh’s virtue will triumph in the end.

While All Fall Down and, with rather more conviction, The Castaway Convict set diverting adventure yarns in historical contexts and dress them in authenticating atmosphere and period detail, Susan Arnott’s The Astrolabe (Lothian, $14.95 pb, 176 pp) goes further. In this case, although there is a slender personal story threaded into the weave, the historical context is itself the adventure. In 1788 two French ships, the Boussole and the Astrolabe, under the command of the Comte de Lapérouse, disappeared in the South Pacific on their way home to France from Botany Bay. Forty years later, ten-year-old Lucien Cannac ships as cabin boy on a second Astrolabe, sent to discover the fate of the first. The novel begins with a glimpse of the first expedition arriving disappointingly behind the British in Botany Bay, then glances at the beheading of its instigator, Louis XVI, who ponders its fate the night before he dies. Then it is into the story proper, onto the second Astrolabe, into a swaying bunk deep in the smelly orlop, up the pitching mast as a terrified lookout, over the side in a longboat in a vain attempt to save a drowning mate. The cabin boy has carte blanche. He reminds the captain of his own son, dead of a fever at seven, so Dumont d’Urville takes the lad under his wing, teaching him his letters and keeping an eye on his health and safety. Not everyone is so well-disposed, of course, and tension is provided by the suspicious antagonism of the headstrong and crooked sailor whom Lucien would most like to have as his friend.

This highly romantic story has a bit of everything: the comradeship of older men towards a young novice; Lucien’s bashful but steadfast affection for the girl he meets in The Rocks at Sydney Town; the struggle of men and ships against the elements; and confrontations of various tempers with the native inhabitants of their Pacific landfalls. There is even a benign paternal ghost to help out when things get really tough. Not everything works (particularly the front-cover illustration) but there is an attractive verve and authority to Arnott’s springy prose, with its atmospheric garnish of simple colloquial French, that will carry the reader along and still the questions one might have been tempted to raise.

Our Enemy, My Friend (Scholastic, $16.95 pb, 169 pp) is set in 1915, when its putative writer turns thirteen. It is a gentle, homely account of Emma Shelldrake’s last year in primary school, as the local Adelaide Hills population of Australian and German-Australian lads go off to fight at Gallipoli and on the Western Front. Emma worries about her friend Pete Morgan, who is in the Light Horse Brigade. She also shares best friend Hannelore Wagner’s anxiety over her brother Kurt, who has changed his name to Kenneth Warner in order to be accepted into the AIF. Information about the war is supplied in letters from Pete and lessons from Emma’s teacher, whose son is fighting with the British army in France. But the war really comes to Emma’s doorstep with the internment of German neighbours on inhospitable Torrens Island, the changing of Germanic place names to innocuous English ones and the racist attacks made by some Australian families on the German settlers – many of them by now second- or third-generation Australians – whom they have known virtually all their lives. Emma winces at the taunt ‘Hun-lover’, but her hurt and confusion on persecuted Hannelore’s behalf are infinitely more painful. Jenny Blackman builds up a broad, effective picture of this shameful period in Australian history in Emma’s naïve young voice and with a host of telling everyday touches.

Comments powered by CComment