- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Complex organisms

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Families are curious entities. They are, by simple definition, households of individuals bound by common lineage. But they are also complex organisms, as these three novels show. Families nurture the individual and offer a refuge from the problems of the larger world, yet they can also impede the growth of their youngest members, who seek their own place in the world and attempt to shape their own responses to it.

- Book 1 Title: The Lace Maker's Daughter

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan, $16.95 pb, 249 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

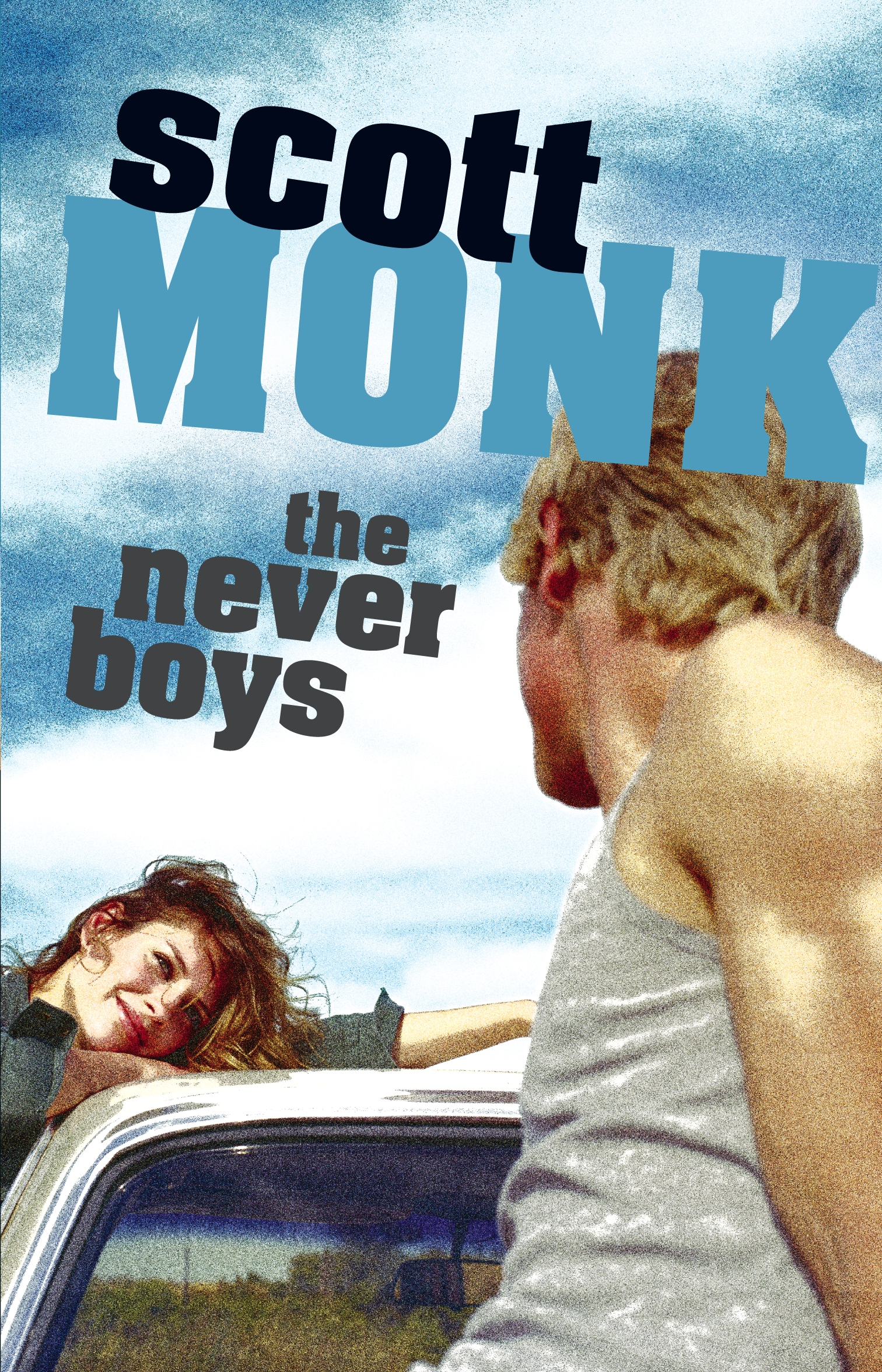

- Book 2 Title: The Never Boys

- Book 2 Biblio: Random House, $16.95 pb, 321 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

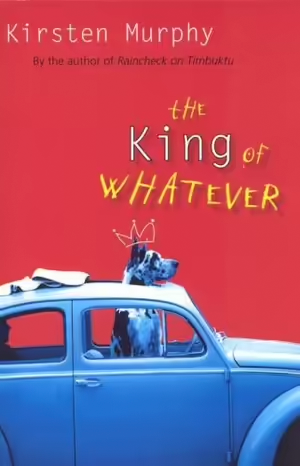

- Book 3 Title: The King of Whatever

- Book 3 Biblio: Penguin, $18.95 pb, 287 pp

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

The Never Boys opens dramatically, if incredibly, with a contingent of police halting a Nullarbor freight train in the middle of the night in search of a runaway boy, sixteen-year-old Dean Mason. Given the urgency of this operation, the reader wonders throughout the breathlessly related prologue what the boy’s crime must be (presumably something quite heinous). As soon as the young protagonist evades the manhunt and settles into the anonymity of farm labour in the Barossa Valley, Scott Monk eases off the hyperbolical prose and settles into a surprising story of the fatefully intertwined lives of two troubled young men, the ‘never boys’.

Dean raises people’s suspicions with his grudging, flighty manner. He is loath to reveal anything about himself and draws little sympathy from fellow characters. However, the owner of a sheep property takes him on and puts him up in the shearers’ quarters. She is a tough-minded divorcée, who doesn’t tolerate any nonsense, least of all from her feisty teenage daughter Zara, who resents the claustrophobia of small-town life and the constraints imposed by her mother. Young Zara is a pivotal character in this novel. Her rebelliousness is a foil to Dean’s reserve and, despite their differences of personality, their circumstances are surprisingly similar; in their own ways they are both on the run, seeking a new identity but thwarted by those with whom they must live.

Another character is crucial to Dean’s dilemma of identity – a recently deceased veteran shearer named Clive. Dean happens across a bundle of old correspondence belonging to Clive. Beginning during World War II, and played out for many years thereafter, it progressively tantalises Dean with its story of unrequited love and dislocation. From this point, Dean starts to appeal to the reader as he immerses himself in the correspondence’s sad history. His continued harassment by the suspicious local cop and his competition for Zara’s attention are effectively woven into his quest for the truth of Clive’s life – a life of secrets and denied identity that is uncannily similar to his own. When the reason for Dean’s false identity and flight is cathartically revealed, the prologue’s true nature is too: an exaggerated hook, way out of proportion to the circumstances that follow.

History also drives a quest for identity in Gary Crew’s The Lace Maker’s Daughter, an intricately crafted novel of compelling story and insight. As with The Diviner’s Son (2002), this is a multiple-voiced murder mystery, set largely in colonial Tasmania. As with so many of Crew’s novels, it centres around a troubled youth who is, for some deep-seated reason, alienated from those around her. Here, it is ‘Tabby’ Bartlett, sole child of an elderly couple who live an insular life in an ostentatious old family seat, ‘Camelot’. Tabby has a troubled history: she is a precocious teenager and aspiring writer who is confined to home after some alleged incidents of violent, anti-social behaviour. She is also psychometric: she can supposedly divine the history of persons or events by touching objects associated with them.

Tabby finds a wooden bobbin and nags her parents about it. The object marks an entrée into the somewhat sordid history of Tabby’s namesake, her great-great-grandmother Adelaide Bartlett, who was an equally wilful young woman and lived in the same mansion. Tabby’s parents acknowledge that Adelaide was rumoured to have murdered her own parents. Thus begins an absorbing psychometric investigation into the chequered past of the allusively titled ‘Camelot’.

The compulsive quest to discover the truth about the lace maker’s daughter excites Tabby, whose narrative style has a distinctly Victorian flavour. It is also deeply intriguing to the reader, as various objects call up characters and recount their particular, and somewhat guarded, perspectives on the tragic history of ‘Camelot’. Each adds texture to the sustained metaphor of lacemaking; the respective accounts fill in the ‘voids’, the patterned holes that create the appeal of lace. More than ten different players from Adelaide’s life weave this richly textured story to the novel’s present-day conclusion: her farmhands and surreptitious lovers; her dowager aunts; the enigmatic undertaker; and past and present ‘Camelot’ housekeepers, whose many similarities cement the parallel nature of the two households.

The family of Joe King (pun intended), in The King of Whatever, is the happiest of the families represented in these novels, at least superficially. His is a suburban, university-educated family, comprised of professional parents, a successful daughter in overseas employment, a son studying medicine, and Joe, a Year 12 student at the bottom of the heap. It is a tough life living in a household of high achievers when you are regarded as a bit of a loser and an aimless follower. Joe is resigned to the fact. He even sees parallels between himself and his brother’s dog – loved by all but usually overlooked or taken for granted.

Joe settles into this role within his family, among his peers at school and with the local supermarket staff. Though written in the third person, the book is full of entertaining, self-deprecating humour as Joe finds perverse pleasure in mediocrity. His resignation is a bulwark against the demanding dynamics of family life, school expectations and the shifting emotional ground of his social life. Joe is the quintessential underdog, the quiet achiever. He is an instantly likeable lad whose self-effacement belies a strength of character lacking in his companions. He is a larrikin survivor. Larrikins have always found a sympathetic place in the hearts of readers; Joe will ultimately find his place there, alongside the likes of Lockie Leonard.

As with so much recent fiction, these novels appear to have been struck by the spellcheck gremlin. It may be a trivial matter, but incorrect word usage does impede a fluid, enjoyable read. Errors include ‘baited breath’, ‘ice flows’ for ice floes, ‘honing in’ instead of homing in. The surname of Margot Fonteyn is misspelled as ‘Fontaine’. More vigilant proofreading would be appreciated.

Comments powered by CComment