- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Non-fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Lost in translation

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The first time Mary Ellen Jordan’s name appeared in ABR (June 2001), it was followed by a brief, heated exchange. Bruce Pascoe responded to her ‘Letter from Maningrida’ mixing accusations of betrayal with a series of familiar analogies, in a stern warning that this kind of fearless journalism was not wanted. Melissa Mackey moved to Jordan’s defence. She had read courage, not fearless journalism, and, in open frustration, ended her reply by simply asking: ‘then what can we say?’ I read Balanda: My Year in Arnhem Land as part answer, part re-examination of that question.

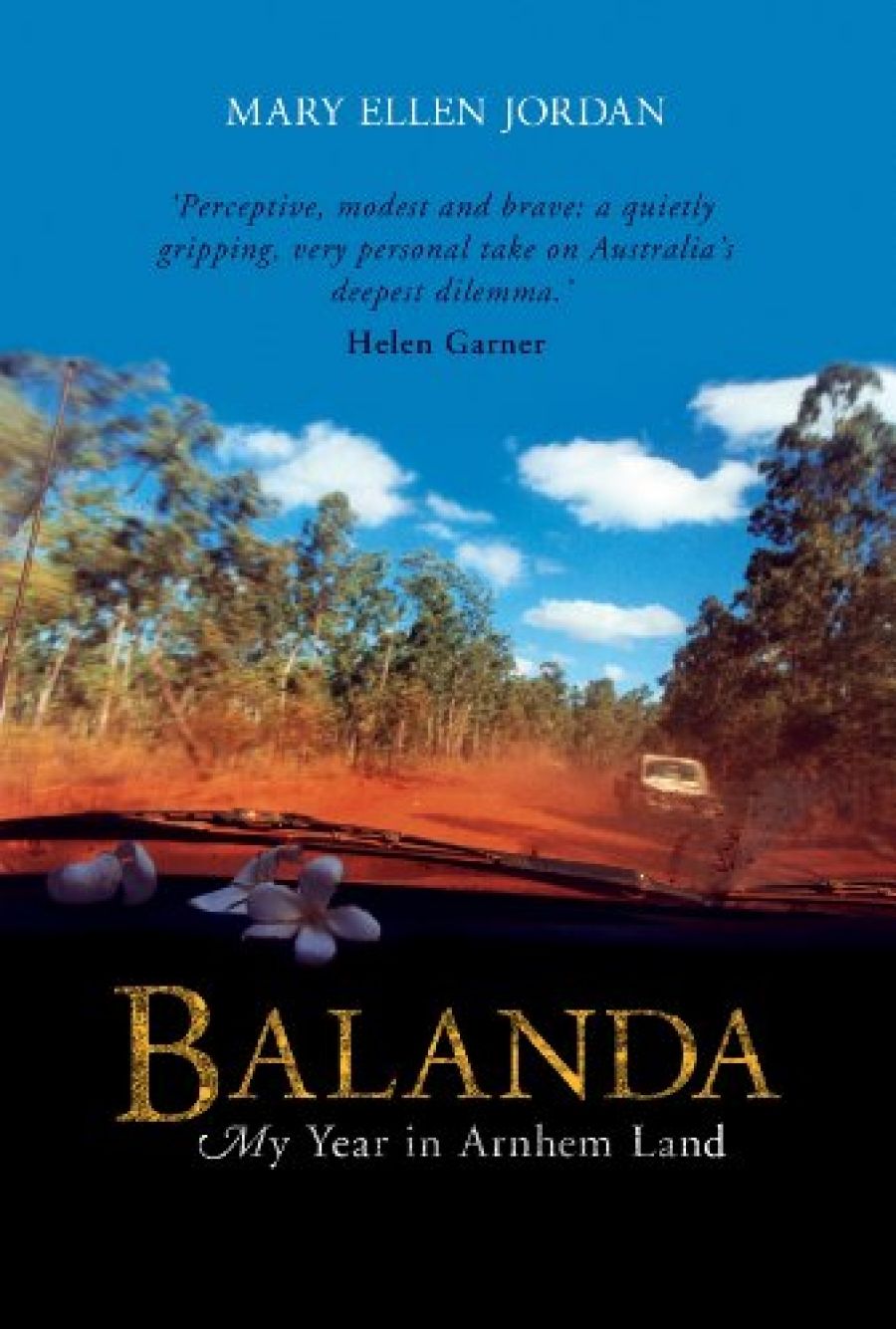

- Book 1 Title: Balanda

- Book 1 Subtitle: My year in Arnhem Land

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $24.95 pb, 240 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Jordan left Melbourne for Arnhem Land driven by a desire to preserve Aboriginal culture and an expectation of working alongside Aboriginal people. The art centre seemed like the logical frontline. It was a typical community-run programme; Aboriginal people in charge of the decisions; Balandas (the Aboriginal word for non-Aboriginal people) there to help balance cultural maintenance while teaching the practical skills necessary to assuming control over the entire operation. Disappointment quickly set in. In Maningrida, it did not work like that. In her job at the local art centre, Jordan was responsible for recording the stories told in the works of art Aboriginal people brought in for sale, for writing a short biography of the artist, and for labelling the work authentic before it was shipped outside the community. The reality was that she had become part of an indispensable barrier – preservation and protection crudely translated into doing all the work.

The work was of a distinct kind. Balandas spent their time applying for money, initiating programmes and completing forms. The Aboriginal men and women worked, too. They formed a transient, come-and-go-as-you-please workforce known more formally as the Community Development and Employment Project. There was always a continuous stream of CDEP works coming in and out of the art centre. They generally worked in the warehouse, sorting out paintings, judicially coating them in Glen 20, and packaging them for shipping. The juxtaposition is dramatic: the art centre brought them side by side; their responsibilities kept them worlds apart.

Attempts to cross that imaginary divide were rare. Most were content (Balandas and Aborigines alike) with how things ran in Maningrida. The divide meant convenience. So, when Samson, a young Aboriginal man, left the warehouse and entered her office, Jordan was shocked. Maningrida did not run like that. When Samson first came to the art centre, Jordan liked him instantly. He was ‘the first to switch to English when a Balanda walked by, to make a joke, to flirt or just to say hello or make conversation’. Samson was intrigued by Balanda culture and was keen to learn how to use the computer. His English was relatively good, and he soon learnt the keys and printed out the biographies required for the artwork. When a painting came in needing some new documentation, Jordan decided to help Samson write it. He struggled, pausing again and again to ask whether this or that word was the right one. Eventually, he made it through the three sentences and together they printed them out. The meaning was clear, but to any Balanda it would read as ungrammatical and uneducated. Jordan’s instinct was to fix it; to make it digestible outside the community. Samson had struggled for that moment across the divide. It was more than a decision of changing the words.

Jordan had struggled for her own crossing, too. Valerie, an Aboriginal woman who had been photographed for a book the art centre was helping to organise, came in to explain the print in which she stood in thigh-deep water using a fish trap made by her mother. Pointing out her father, mother and brother, Valerie explained that they were hunting for mud crabs and yams. Jordan pointed to other parts of the photo. Resting her finger on a vine, Valerie told her it was Milil; moving it onto some butterflies, she then said Merle Merle. Jordan tried repeating the words. They stuck to her tongue and finally awkwardly came out as Melli Melli. Valerie laughed and said them again slowly and loudly.

Valerie continued to tell her more about the print. The Milil and Merle Merle meant that it was a good time for mud crabs and yams. Here, however, Valerie got stuck. As Jordan put it: ‘in her language, Kuninjku, and in her social universe, you need to know the relationship the person you’re talking to has to the person you’re talking about so that you can use the right terms for everybody.’ Valerie solved it by giving Jordan a skin name, Belinj – or sister. After getting the pronunciation right and flashing through a kinship lesson, Valerie resumed her explanation with newfound detail. Jordan now had a relationship to everyone in the print.

In this personal, deeply reflective book, Jordan makes it clear that Maningrida is not a place for simple answers. She shows us that words such as ‘outcomes’, ‘opportunities’ and ‘cooperation’ have no weight here. The problem is not open conversation. The problem is that few shared meanings and experiences have been forged across that divide. We do not need another dressed-up vocabulary and a series of quick fixes; we must honestly acknowledge the real-life difficulties of living with our differences. To do that we need only start with one or two shared words.

Samson’s exhaustion at the computer, Jordan’s struggle to read the deeper significance of the photograph, show us exactly how hard-fought one or two of these words will be (I hope Jordan sent Samson’s words as they stood). A year in Arnhem Land had led her to ‘the realisation that nothing was simple, that everything was paradoxical, that there were no clear answers’. Sometimes we don’t need them; finding the right question is enough.

‘Balanda’: it is easy for us to take on the strangeness of the word, but it is much harder for us to live with the realities that come with it; harder still to find a shared, lived-in meaning. Open conversation is not going to solve that, patient understanding will. What, then, can we say? Before we can say anything, Jordan has shown us that we must, at least, start with that.

Comments powered by CComment