- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Military History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Virtual battalion

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In earlier works, Russian-born historian Elena Govor has written of changing Russian perceptions of Australia between 1770 and 1919 and – in My Dark Brother (2000) – of a Russian-Aboriginal family. In her latest book, Russian Anzacs in Australian History, the canvas is broader. She investigates the third largest national group (after the British and Irish) to enlist in the First AIF. Her indefatigable and imaginative research has taken her on a ‘quest for the thousand Russian Anzacs’ who comprised ‘a virtual battalion’. More exactly, they amounted to one in every four male Russians who were in Australia at the outbreak of the Great War.

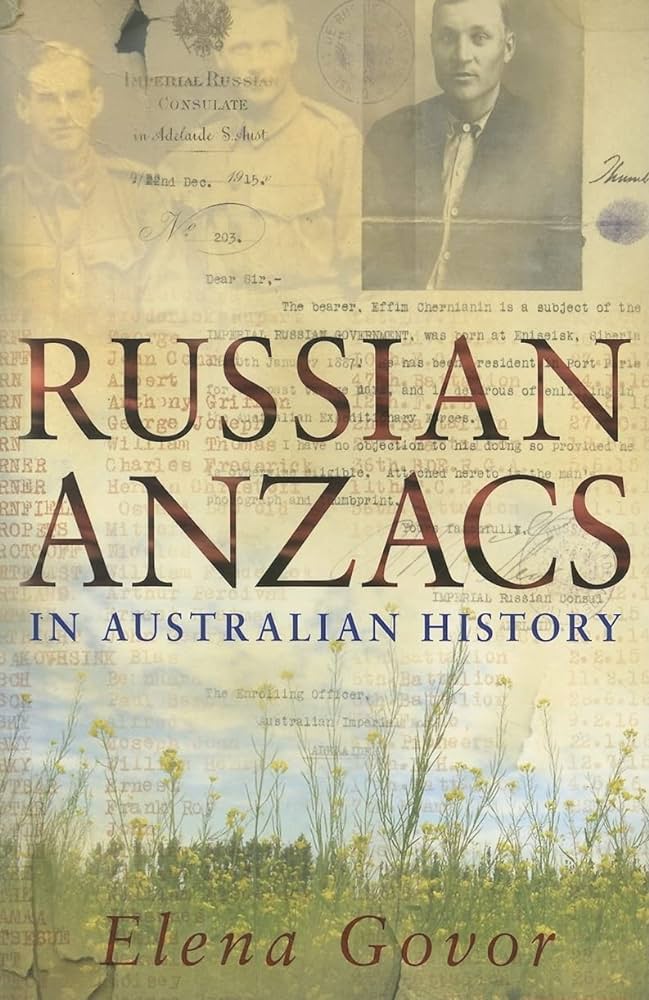

- Book 1 Title: Russian Anzacs in Australian History

- Book 1 Biblio: UNSW Press, $44.95 pb, 310 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

By ‘Russian’, Govor means people of the Russian Empire, drawn from ‘at least twenty different nationalities’ and, to varying degrees, subject to a process of ‘Russianisation’. What being Russian entailed – in terms of origins, languages, personal political allegiances and the suspicion aroused among Australian authorities – is a persistent interest of the book. In pursuing her enquiries, Govor felt at first that it was ‘like trying to listen to a series of disconnected voices’. Gradually, as she spoke to descendants of these Anzacs, and pursued archival research, a compelling narrative became possible. Early on, Govor offers an unexpected but heartfelt paean to Australian bureaucrats, ‘who watched, annotated and recorded the lives of these Russians’. They were, she reckons, ‘building a paradise for future historians’.

Throughout a story strange and heterogeneous, Govor organises her material chronologically and statistically. In the first respect, she is concerned with how Russians assimilated within the Australian armed forces, and with the difficulties that beset so many of them in the decades after the war. In the second, Govor tabulates how similar were the ages on enlistment and the casualties among Russians and native-born soldiers. Her notable gift for storytelling means that she punctuates the larger narrative with incisive vignettes. Thus, at the beginning of Russian Anzacs, she relates how the assassination of a police chief and poet at Nizhny Novgorod in 1905 led to his son’s eventual arrival in Australia. This single story also illuminates an interpretative challenge for the whole work.

Why did the Russians come to Australia? This is perhaps a question that can never find a wholly satisfactory answer. Some sought better economic circumstances than they found at home. One tossed a coin and Australia won out over Canada. A significant proportion were Jews, rightly fearing persecution. Another group were seamen who had already jumped ship, or who found themselves stranded when the war began. In Australia (and later, at war), their primary problem was learning the language. But, for some, the metamorphosis was successfully managed. Alfroniza Morozoff, from Odessa, became Jack Morris, bridge carpenter of Bunyip Swamp, Gippsland. Yet the Australian government’s power to refuse naturalisation – even to those Russians who had served in the war – remained a potent weapon and a source of anxiety, especially in the cankered atmosphere after the Bolshevik Revolution and Russia’s withdrawal from the war.

The central section of Russian Anzacs is concerned with their experience of combat at Gallipoli and on the Western Front. Here, Govor draws out individual stories from the massed involvement of troops. Lieutenant Colonel Eliazar Margolin became the highest-ranked Russian Anzac, going on to command the British Jewish Regiment. When he died, this secular Jew’s wishes were to be buried in Israel, where one of the mourners was David Ben-Gurion, the prime minister, who had served under Margolin. Alexander Sast was wounded and taken prisoner at Gallipoli, then transferred to a camp in Bulgaria, from which he escaped into Russia. But he only wanted to fight in the Australian army. Another crucial question is implied: who were the Russian Anzacs fighting for – motherland or new country? Sast eventually reached Britain and then joined an Australian army unit in France.

His story is one of several that Govor tells that might have made books in themselves, such as that of Basil Greshner, who went back to Russia after the war to check on the well-being of his family and narrowly evaded the secret police. As she follows the often-precarious lives of the returned servicemen who settled in Australia, Govor records the prejudice that they met (sometimes mitigated through membership of the RSL), the resentment that war service did not guarantee naturalisation, and the hardships of the depression. She writes that some of the Russian Anzacs ‘remained vagabonds until they died’, but that surely applies to the First AIF at large. Govor’s book, which is published with the assistance of the National Archives of Australia (where a good deal of her work was done), is yet another publishing achievement for the University of New South Wales Press. It is also a triumph for the author, who has adroitly and sympathetically marshalled material that seemed at first to be ‘like reading a book of short stories without endings’.

Comments powered by CComment