- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Non-fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Survivor in a lesser world

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the winter of 1968–69 the buildings of the Institute for Social Research at the University of Frankfurt – the symbolically resonant home of what had come to be known as the Frankfurt School – were occupied by students. The police were called in, and Theodor W. Adorno, one of the great radical theorists of the twentieth century, pressed charges against a young man whose doctoral work he was supervising. Two months later, a group of women forced their way into Adorno’s lecture, handed out leaflets proclaiming that ‘Adorno as an institution is dead’, and ‘surrounded him, strewing flowers, performing a dumb show and … baring their breasts’. In action after action, the contempt of the students for the radical theorists of an older generation was made clear.

- Book 1 Title: Adorno

- Book 1 Subtitle: A political biography

- Book 1 Biblio: Yale University Press, $69.95 hb, 239 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: The Cambridge Companion to Critical Theory

- Book 2 Biblio: Cambridge University Press, $59.95 pb, 388 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

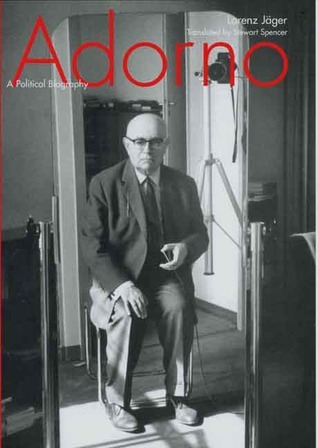

The cover of Lorenz Jäger’s Adorno: A Political Biography shows a small, melancholy man staring into a mirror and pressing the remote trigger release of a camera which, reflected behind him and capturing his and its own reflected image, seems to float in air. The photograph was probably taken in the last years of Adorno’s life – he died in August 1969, dispirited by the hostile rejection of his work by a student movement that had earlier seemed to take inspiration from it. But Adorno’s melancholy goes deeper than this political failure. His relentlessly pessimistic vision of a world dominated by the mass media, by corporate manipulation and by the crippling of popular political will, and even of the ability of the administered masses to grasp and to resent their own loss of freedom, made him think of himself as a survivor in a lesser world. His world was that of the heroic and rigorous musical modernism of Arnold Schönberg, of Anton von Webern and of his teacher Alban Berg. This most subtle and insightful of music critics and theorists had no understanding of, and no interest in, jazz or the blues, let alone commercial culture more generally; his twelve-year exile in the US taught him only to despise the industrialised products of Hollywood and Tin Pan Alley.

Yet Adorno, like Herbert Marcuse, had at least sought to engage with the student movement of the 1960s. The other major figure of the first generation of Critical Theorists, Max Horkheimer, moved during his own time of exile from an uncompromising critique of capitalism to full-blooded support for the US invasion of Vietnam, and an idealisation of the US as a bastion of constitutional liberties. His is a classical twentieth-century turn from political radicalism to conservatism.

What did Critical Theory ever have to offer socialist politics in the twentieth century? No more and no less, I suppose, than any other left-oriented theoretical movement of its time. It shared a fate with the rest of what Perry Anderson calls ‘Western Marxism’ – meaning thereby the versions of Marxism, from Georg Lukács to Louis Althusser, that tried to elaborate an alternative both to an increasingly rigid Marxist orthodoxy and to a social democracy that was losing whatever socialist commitment it had once had. Anderson’s condemnation of the increasing divorce between these theorists and socialist practice is all too facile: the foundations for a socialist politics were progressively weakened as Stalinism took hold of the Soviet Union and fascism of Italy, Spain and Germany; as religious and political anti-communisms as well as a mediated culture of consumerism shaped new forms of politics; and as the Western working classes made the calculation that the costs of revolution were higher than the costs of a settlement with the capitalist order.

In the case of Critical Theory, however, the failure of theory to develop an active relationship with a revolutionary working class – the theory was, after all, largely shaped in Germany during the period of that class’s defeat by, and capitulation to, Nazism – was exacerbated by its sense that political action was itself contaminated by the order it opposed. In a world saturated by commodification and controlled in all its dimensions by corporate power, politics is already a lost cause. What takes its place is what is variously called a ‘politics of engaged withdrawal’ and ‘The Great Refusal’: a disengagement that carries the value of an absolute rejection of the existing state of things. It was the absolutism of this refusal that spoke to the students of the 1960s.

If Critical Theory (by which I mean the central group of Horkheimer, Adorno, Marcuse, and a couple of others, including Jürgen Habermas at a later date, but not the more peripheral group of figures such as Walter Benjamin, Erich Fromm and Klaus Neumann) is still of interest it is for other things than its politics. Indeed, much of its political analysis now looks naïve, with its overestimation both of the extent of systemic social control and of the centrality of the state of reason to the movement of history – its understanding of capitalism above all as a ‘deficit of rationality’. Julian Roberts speaks of the political conservatism of Adorno and Horkheimer’s Dialectic of Enlightenment (1944), with its crankiness about mass culture and its resort to a version of Bildung (cultural self-formation) to cure the ‘illness of the spirit’ that it diagnoses. What Critical Theory did get powerfully right, however, was its critique of positivist social science.

This may sound like small compensation for a failed politics, but, from a more modest perspective, the contribution of Adorno, Horkheimer and the early Habermas to questions of the methodological form and the social function of the social sciences is substantial. In brief, Critical Theory posits the historical and social interrelation of the subject and the object of knowledge. The object of inquiry is never immediately given but is always and by definition theory-laden, and conversely the subject of sociological or philosophical inquiry is situated within social and disciplinary relations rather than in an empty space of observation or speculation. The constitution of subject and object is never merely a theoretical matter but is a function of social forces, interests and desires, and of their historically specific force and their embedding in social institutions. The explanation of states of affairs involves a plurality of factors; rather than a reduction of social forms to economic forces and relations, economic, political and legal processes and structures are refracted through ‘cultural’ categories, just as ‘culture’ in its turn is situated within its political, legal and economic conditions of existence.

I take this set of principles to constitute something like the core position of Critical Theory, from which a rich body of other work radiates; it is worked out in a series of major texts, from Horkheimer’s ‘Traditional and Critical Theory’ of 1937 to the contributions of Adorno and Horkheimer to the ‘positivism debate’ of the 1960s. The ideas clearly owe much to classical Marxism, and they may now sound obvious or dated. Yet their influence has been historically significant, and they remain in many ways relevant to contemporary habits of thought.

If you want a guide to them, however, these two books are probably not the best place to start (Martin Jay’s The Dialectical Imagination, 1973, is still a much better book for most purposes). Jäger’s biography of Adorno is excellent on the musical dimensions of Adorno’s thinking, and it has fascinating, gossipy vignettes of his peers – Bertolt Brecht, Paul Celan, and Siegfried Kracauer, for example; but Jäger is fundamentally hostile to the whole project of the Frankfurt School, and one wonders why he bothered.

The Cambridge Companion to Critical Theory is a worthy scholarly exercise with several interesting pieces: Simone Chambers on the politics of Critical Theory, and Moishe Postone on the political diagnosis of ‘bureaucratic capitalism’ formulated in the 1930s and 1940s. Much of it, however, still seems to be written in a kind of half-translated German (‘Not so much the concept of reason needed to be discarded as the discursive distortions to which it historically had been subjected’), and the key gambit for many essays is to identify the moment of error in the theory, the avoidance of which would have redeemed both the theory and the politics that is assumed to follow from it. One of the clearest lessons to be drawn from the fate of Critical Theory, however, is that getting the theory right is not what makes politics work.

Comments powered by CComment