- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Transcending genres

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Knitting, the first novel from ghostwriter and former professional knitter Anne Bartlett, tells the story of a newly widowed academic and her unexpected friendship with a gifted knitter that enables her to move on with her life. Bartlett’s rich (and uncredited) experience of writing other people’s stories puts this intimate exploration of women’s friendships in a different category from your average ‘chick lit’. Age journalist Graham Reilly is another writer who transcends his genre in Five Oranges, a crime novel about the ragtag adventures of a tight-knit circle of working-class Glaswegian friends and their on–off tangles with the Saigon mob. Part of the reason that these two novels are so much better than many in their respective genres could be that they go beyond formula and caricature.

- Book 1 Title: Knitting

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, $22.95 pb, 272 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

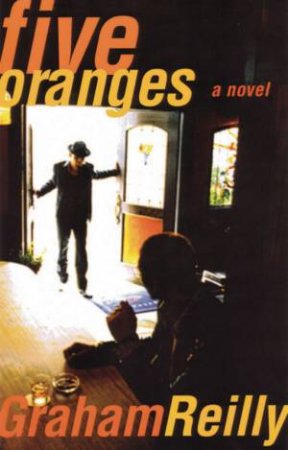

- Book 2 Title: Five Oranges

- Book 2 Biblio: Hodder, $21.95 pb, 362 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Knitting centres on the accidental friendship of Sandra, a tightly wound, well-off academic grieving after her husband’s recent death from cancer, and Martha, an eccentric who lost her own husband at an early age and who combines a talent for kindness with an even greater talent for knitting. Sandra and Martha meet through an instinctive act of goodwill – entirely characteristic for Martha, rare for Sandra – when a homeless man collapses in Rundle Mall, in Adelaide. Sandra observes Martha struggling to get help and reminded of her husband’s collapse in public, comes to the rescue. The pair strikes up an unlikely friendship based on their mutual passion for knitting – Martha as a hands-on artist, and Sandra as an academic specialising in the study of ‘women’s work’.

Bartlett uses the friendship of these polar opposites – both widows (and both, in their own way, perfectionists) – to explore the different ways people are marked by grief, and the ways in which they struggle to restore meaning to their lives after such an experience. The newly widowed Sandra stumbles through her days beneath a thin veneer of ‘business as usual’ – doing what she has always done, but without passion or joy. While Martha lives independently and mostly happily, her grief leaks out during casual conversations, and she still suffers after-effects from the breakdown she experienced following her husband’s death.

Martha lives her life in the same way that she knits – instinctively, viscerally, with no desire for the formal accolades of fame or fortune. She enjoys appreciation from the recipients of her work, and the pleasure of the work itself. When Sandra dreams up an exhibition of vintage knitted work, featuring Martha’s handiwork and her own research, it provides Sandra with a reason to get out of bed in the morning and with a boost for her esteem as academic interest in the project grows. However, the reluctant Martha begins to unravel under the pressure to perform, revealing a pathological fear of failure underneath her ostensibly sunny exterior. As Sandra wilfully ignores the signs that Martha is in trouble, seeing only the threats to her exhibition and her own reputation, it becomes obvious that to salvage her humanity Sandra must begin to relinquish control over the people and events in her life.

Knitting is a well-crafted work of popular fiction, thoughtful and genuine. Bartlett has created believable and identifiable characters in the stitched-up Sandra and pliable, generous Martha, who could easily have descended into saintly caricature without the odd moment where her eccentricity grates on the other characters, or when it’s revealed that she also has had moments of not thinking about how her actions will affect others. Middle-class literary readers will probably recognise uncomfortable elements of themselves in Sandra, but also enough good qualities to empathise with her plight and cheer on her recovery.

While Knitting portrays two women’s response to loss, a major focus of Five Oranges is one couple’s response to the pressures of unrelenting ordinariness. The sequel to the well-received Saigon Tea (2002), this book revisits the lives of Glasgow couples Frankie and Eileen (blissfully happy) and Jimmy and Stella (depressed and stuck in a rut), and also of Frankie’s Saigon-based brother Danny and his family (who have fled to Melbourne to escape Saigon gangsters).

I’ll get my one whinge out of the way here: as someone who hadn’t read the first book, though I appreciated the plot summaries that frequently crop up, after a while I did find myself cursing the seemingly endless recitations of ‘the time we all went to Saigon to save Frankie’s gambling brother Danny from Vietnamese gangster Nam Cam, otherwise known as Mr Five Oranges’.

Reviewers widely noted Reilly’s wicked ear for dialogue in his first book, and I can confirm that it is active here, particularly in his characters’ internal monologues. He delivers a fast-paced, if somewhat predictable, crime story that is also very smart. The canny riffs on modern society range from quips such as ‘I hear the kitchen is sexy now’ and ‘they say women are the new men’, to observations on the gentrification of Glasgow pub menus and Fitzroy’s Brunswick Street.

Reilly’s black humour is nowhere more evident than in his portrayal of Jimmy’s mid-life crisis, which manifests itself in a lack of interest in his wife, a prurient interest in articles about improving your butt in Cosmopolitan magazine, and a general dissatisfaction with his lot. Frankie observes: ‘It was funny how people’s motivations ebbed and flowed ... You could be in the depths of despair, seeing nothing but blackness ahead, and suddenly you find something to hold on to, to give you hope.’ In Five Oranges, small things – a gift of crayfish, a humorous remark from a child or an evening of laughs with friends – are what the characters hold onto, although it’s overseas travel (to Australia to visit Danny and Mai; to Saigon for another battle with Nam Cam) that prompts Jimmy and Stella to see things in a new light.

The world of Five Oranges is chiefly attractive for the camaraderie and geniality of its characters. As in Knitting, they weave together the ‘families’ that sustain them through a blend of lifelong friends, chance encounters and traditional family ties. One character observes that migrants form new families wherever they go, often unusual ones, but this is actually as true of the couples who live in Glasgow as of those who make new homes overseas. The strongest bonds are as likely to be between neighbours as between blood relatives. Reilly’s characters may squabble and complain, but they are also willing to risk their lives for one another.

It goes without saying that this book will appeal most to those who have read Saigon Tea, but it will also please anyone looking for that elusive ‘intelligent light read’.

Comments powered by CComment