- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Short Stories

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Florid rhetoric

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Carmel Bird stakes a great deal on her prose style. The delicate latticework of imagery, the fascination with detail and colour, the allusions, the linguistic gamesmanship, the florid descriptive passages (and Bird’s writing is literally florid: there are flowering plants everywhere) – these are at least as important to her fiction as narrative. Her writing does not just revel in the sensuality of language; at times, this sensuality shapes the form. In her long story ‘Woodpecker Point’, for example, the action is veiled in lush rhetoric. The intention is to tease out small correspondences and to develop an intricate verbal pattern. So, while the narrative is disjointed, the finely woven imagery is rolled out like one long strip of carpet. This is often true of Bird’s short stories. They frequently centre on strange or sinister happenings, around which grows a delicate bubble of linguistic indulgence.

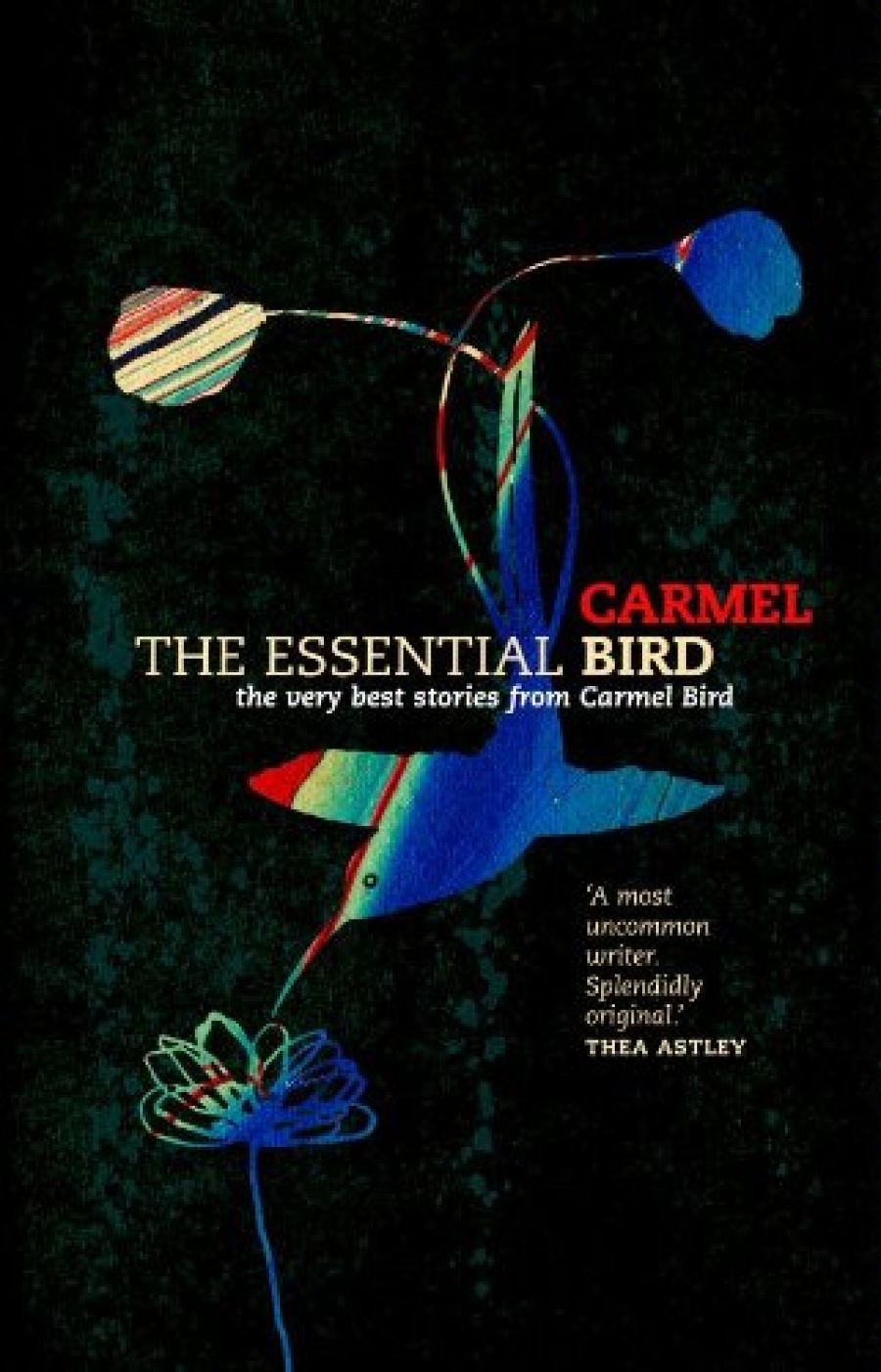

- Book 1 Title: The Essential Bird

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $24.95 pb, 371 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

This emphasis on rhetoric as a driving force – almost the raison d’être – of fiction is a high-risk strategy in many ways. The immediate risk is prose that resembles bad poetry, something Bird does not always avoid. This is from the recent ‘Made Glorious Summer’, the first story in this career-spanning anthology, The Essential Bird (the line divisions are mine):

The lorikeets have moved on

and the afternoons are quieter now

and the rotting spotty Chupa Chups

plop softly to the ground.

The comical effect of this sentence is, at least to some degree, intentional. Bird’s aesthetic, particularly in her recent work, is one of excess. When her heightened prose edges toward the ridiculous, rather than moderating her tone, she will deliberately make it even more ridiculous. Taken in the right spirit, this approach has a certain appeal. There is something mildly orgasmic about arriving at a noun after the fifth or sixth adjective. And Bird is a writer for whom humour is fundamental. She often intends to have the reader cringing and laughing at the same time – and the laughter excuses a multitude of sins.

How one responds to Bird’s writing – how ‘essential’ it ultimately is – depends on the appeal of her unique brand of whimsy. Personally, I think short stories and belles lettres show Bird at her best, a few failed experiments notwithstanding. Her flighty prose can become tiresome over long stretches, but thrives in the quick turnaround of the shorter form where her cleverness and love of concentrated imagery can be utilised to good effect. Her best ideas are witty and concise; her best stories murmur reassuringly in your ear before sliding a blade under your ribs. In some respects, the technique is not far from surrealism. Her fiction frequently aims to give the reader a shock. As the narrator of ‘Major Butler’s Kidneys’ explains, it has affinities with Roland Barthes’s concept of the punctum: ‘the element which rises from the scene, shoots out like an arrow and pierces me.’ Another story refers to a search for ‘the point where consciousness and understanding intersect with unconsciousness and confusion’.

But even Bird’s darkest stories retain a vaguely comical tone. Despite their obsession with death and evil, they are never truly scary or disturbing. Their menacing side is never more than cartoon ghoulishness. They remain safely quarantined in a fantasy land, a faintly ridiculous spookhouse where you can never quite lose your presence of mind and forget that the whole thing is a fake. This is a result of the self-consciousness of Bird’s fiction. Like a great deal of what is loosely called ‘postmodern’ writing, the stories don’t just do something, they tell you how they are doing it. The author never totally disappears into the background but remains a tangible presence hovering over her characters. In ‘Shooting the Fox’, another recent story, the narrator observes: ‘There is sometimes a gracious symmetry to fate which plots its way about the place, criss-crossing country roads and stony hillsides in its search for elegance and balance between happiness and sorrow, between love and hate, light and dark, life and death.’ The rhetorical fluency of this line is almost enough to make one lose sight of the fact that it is completely untrue. ‘Fate’ does no such thing. But then the subject here is not really fate, it is the author herself. The lines are not a metaphysical assertion, they are an aesthetic manifesto that regards imagination as a form of control. As another story declares, ‘I want to feel the anguish and exhilaration of the fiction writer’s power to create and destroy.’

Bird’s author biography quotes her as saying that ‘fiction will only be convincing if it is more artful than life’. When you read Bird’s fiction, you realise what an odd comment this is. Her stories are certainly more artful than life, but they are not really trying to be convincing. Snappy rewrites of Snow White and Little Red Riding Hood obviously have little interest in being realistic. The game is being played on another field entirely, a field upon which the fact that it is a game (and only a game) is always openly acknowledged. There is nothing wrong with this, but stories of this kind invite a certain detachment. They might convince as fiction, but they do not convince as a representation of life. The world of pure language that Bird creates, a metaphorical world that rushes from one image to the next, is also a world in which paper-thin characters are so dominated by their creator they have no life of their own. Bird’s characters are more likely to be defined by something that happens to them than by what they think and feel. Her rhetorical world is full of wonders, but, to be convincing, its inhabitants would have to struggle a little harder against the capricious impulses of a cruel and manipulative ‘fate’.

Comments powered by CComment