- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Non-fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Women on the margins

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Katherine Summers’ memoir of her childhood and Kris Olsson’s biography of Debbie Kilroy have in common histories of violence and abuse against women and children. Summers writes of her early childhood of desperate poverty in London’s East End in the 1960s and of her subsequent time in private boarding schools in a way that emphasises the powerlessness of the child in an inscrutable adult world. In contrast, Olsson traces Debbie Kilroy’s journey from an angry and rebellious adolescence in Brisbane in the 1970s to becoming a battered wife and mother who was imprisoned in the infamous Boggo Road prison after being convicted of illegal drug trafficking. From these beginnings, Olsson recounts the process by which Kilroy becomes a powerful activist and leader on behalf of imprisoned women and troubled teenagers.

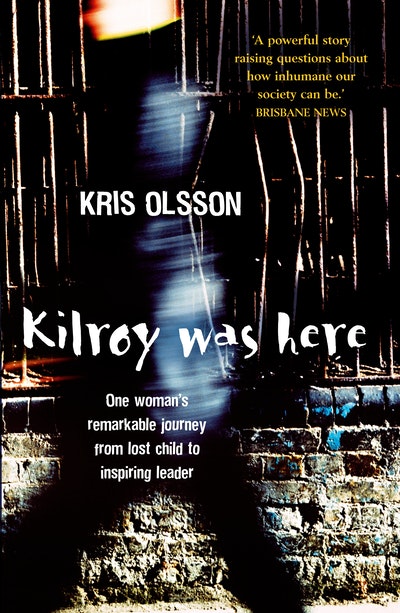

- Book 1 Title: Kilroy Was Here

- Book 1 Biblio: Bantam, $32.95 pb, 289 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

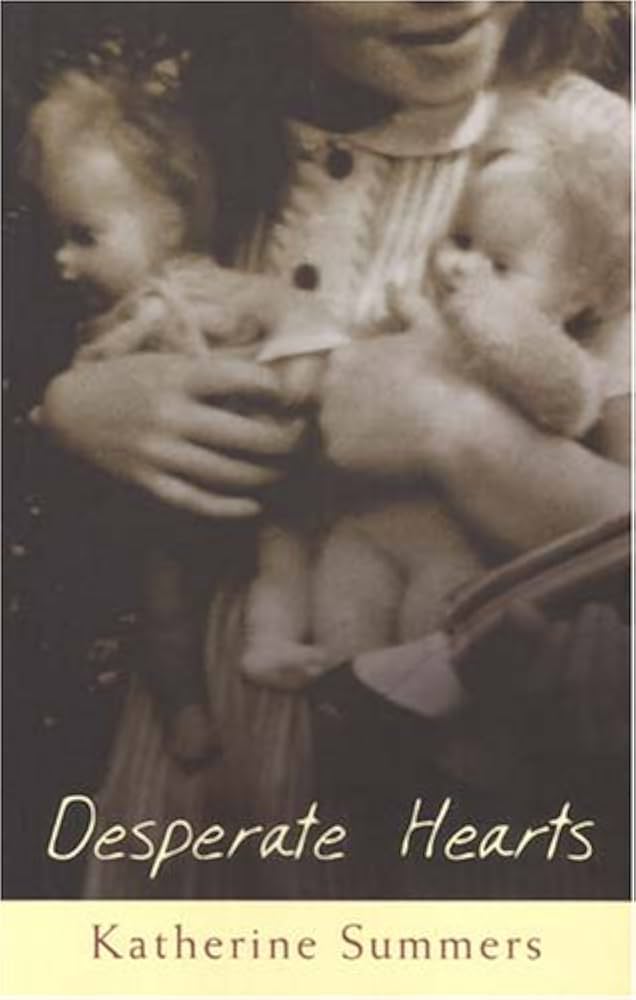

- Book 2 Title: Desperate Hearts

- Book 2 Biblio: FACP, $24.95 pb, 224 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

The first-person narrative of Desperate Hearts strives for a child’s perspective; the voice is deliberately naïve. This is maintained until the last three chapters, when the narrator, now speaking as an adult, emerges to offer a more sophisticated viewpoint. This life-narrative charts the bewilderment and pain of a child whose parents separate after her violent and presumably criminal father has manipulated her mother into prostitution. Because this account is based entirely upon childhood memories – inevitably slippery and fragmentary – the child–narrator expresses no understanding of what is happening. When, after a violent scene between her parents, Summers and her three sisters are suddenly removed from their home and placed into temporary state care, the eight-year-old Kathy knows only that they must stick together. Her subsequent time in exclusive boarding schools, which is funded by her mother’s wealthy lover, is less insecure, but this precarious sense of safety is overturned when she is thirteen and returns home from school to recuperate from surgery on her feet. Looking through a window, Kathy witnesses her father shoot dead the man he blames for the loss of his wife and children.

The story then jumps forward to when Summers, now an adult living in Australia, returns to England to attend her mother’s wedding and embarks upon a quest to find out what happened to her father, now deceased. It seems curious that her enquiry is focused entirely on her quest to understand her father’s, not her mother’s, experience. We can only assume that her mother is still alive and that Summers is protecting her privacy.

This book articulates no anger. It is remarkably non-judgmental of either parent when her father’s violence and obsessive pursuit of the mother is shocking, and the mother’s choice of a life as the mistress of a wealthy man (who must be unencumbered by children) is alienating. The four little girls are dumped in boarding schools, seeing their stylishly dressed mother only rarely, when she offers no explanation for her absence from their lives. Each of her visits is joyfully anticipated by the children, only to be followed by a repetition of abandonment. Summers attempts no psychological or social context for all of this. Instead, we are given raw information based upon memory and quite unmediated by analysis. This is an inherent problem with memoir if it is not in the hands of an experienced writer. Information does not speak for itself, or does so only in a very limited way. Summers leaves her reader wondering what to make of it beyond the obvious fact that children are often mistreated, even by well-meaning adults. When Summers tells us that ‘this is real life after all, not fiction’, she seems to want to preclude the reader’s need, not for fairy-tale endings, but for satisfying conclusions. This is disappointing. Memoir is not ‘real life’. It is writing, a textual representation from which we can expect context and analysis.

Kris Olsson’s biography of Debbie Kilroy does not lack social context or psychological insight. We are given plenty of detail about the world of the subject, the reasons for her life of violence and what seems at times, to a sheltered middle-class reader, like an almost crazed rebelliousness against fairly benign parents. Olsson adopts a stance towards her subject’s story of apparently unflinching honesty, but, unfortunately, her relationship to the subject and her story is never explained.

Theorists of life writing have argued that a democratic biographer must use, as far as possible, the voice of her subject. Olsson achieves this by quoting plenty of direct personal testimony from Kilroy herself, and from her family and friends. The idiom of some of these sources is often confronting, giving the reader access to a world that most will never know. The sections dealing with Kilroy’s life – first in a youth correction centre, where she was placed as a teenager for wagging school and staying out at weekends, and later, her terrible years in Boggo Road Prison – are horrific. Olsson makes it clear nonetheless that Kilroy was no passive victim; she was physically strong and tough-minded, which made her survival possible. The years of Kilroy’s frightening alcohol abuse and participation in domestic violence are more difficult to understand. Although Olsson makes consistent attempts to explain the subject’s self-destructive binges and outbreaks of violence, this pattern of behaviour seems contradictory if we are to accept the testimonials that Kilroy was a loving mother.

This is a painful book to read, at least until Kilroy slowly begins to turn her life around. After the murder of her friend Debbie Dick in jail, Kilroy undergoes a crisis that leads to her relinquishment of the code of ‘payback’ that requires that she in turn should murder ‘Storm’, the perpetrator of the crime. Storm’s own story is so terrible that her propensity to violence is almost understandable. Olsson tells some lacerating stories of the suffering of women who find themselves within the prison system. A central strand of the narrative is Kilroy’s admirable work in establishing a group called ‘Sisters Inside’, which works to improve conditions for women in prisons and to make their transition to the world outside less difficult. One story from the inside is that of the friendship Kilroy develops with Tracy Wiggington, the so-called ‘lesbian vampire killer’. Olsson sympathetically discusses the ways in which the popular press demonised this woman and tells us that eventually, in order to recognise her humanity, Kilroy renames Wiggington ‘Fred’ rather than ‘Drac’, the nickname she had previously given her.

There is a mildly irritating triumphalist trajectory to this life story, but this is unsurprising given what Kilroy has achieved. Since her time in prison, Kilroy has earned a degree in social work, and she is presently studying law. Her deepening politicisation and unflagging loyalty to her mates has meant that she is acknowledged as the power behind ‘Sisters Inside’, now an international organisation. The preface to the book is written by Angela Davis, no less. Kilroy has been awarded the Order of Australia, given the Australian Human Rights Medal for 2004, chosen as Telstra Businesswoman of the Year and involved in the campaign against the incarceration of asylum seekers in detention centres.

If I had not been asked to review them, I probably would not have read either of these disturbing books. Neither has much aesthetic appeal, but the need for truth can override the claims of art. These once-silenced life-narratives of women on the margins matter, regardless of how painful they are to read.

Comments powered by CComment