- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

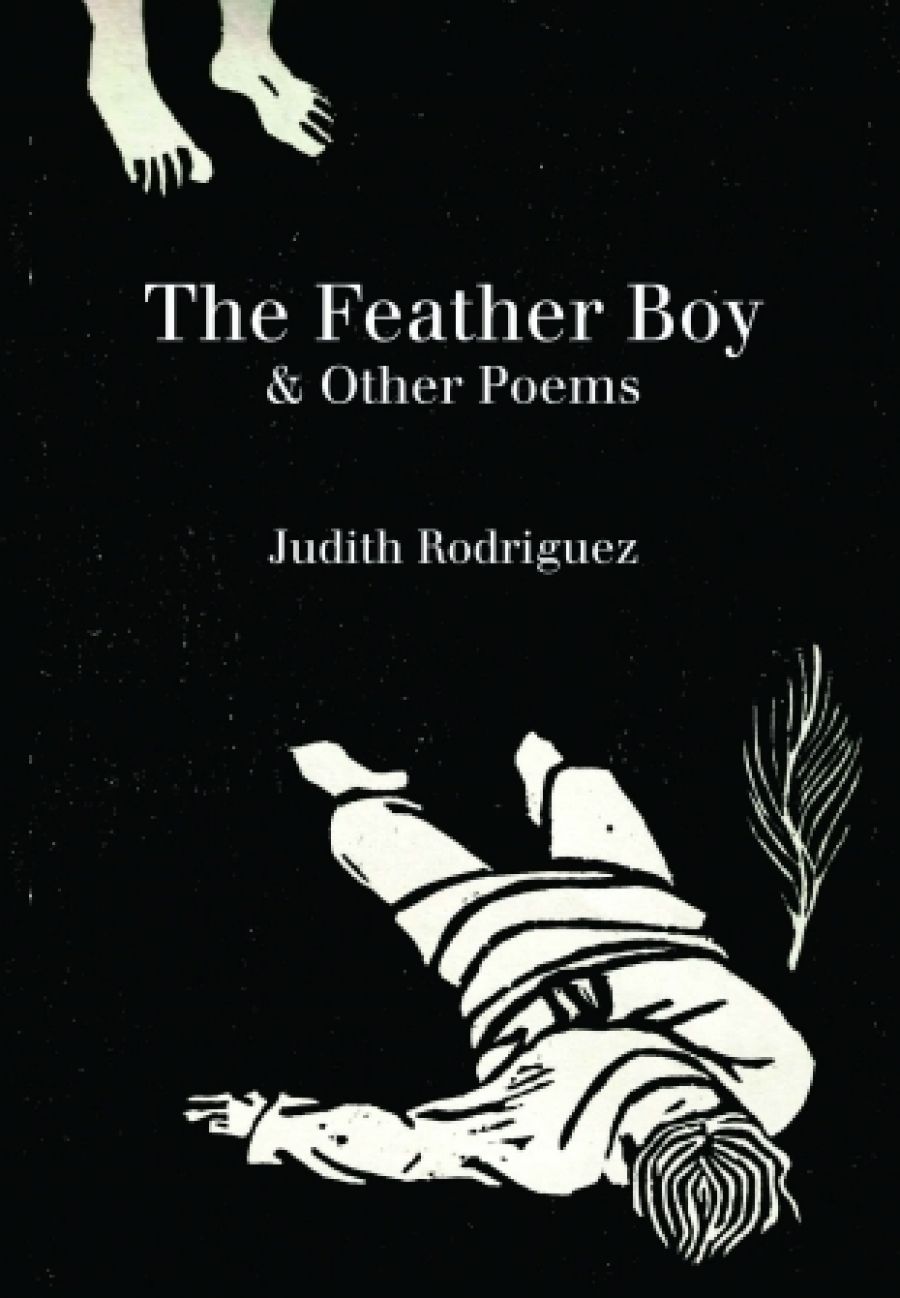

- Custom Article Title: Jennifer Strauss reviews <em>The Feather Boy & Other Poems</em> by Judith Rodriguez

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Judith Rodriguez, who died in November 2018, was a champion of other people’s causes: the right to be heard, the right to freedom from persecution, the right to refuge when such freedom is denied. She was also a champion of poetry and gave generously of her time and energy to fighting its corner ...

- Book 1 Title: The Feather Boy & Other Poems

- Book 1 Biblio: Puncher & Wattmann, $25 pb, 136 pp, 9781925780079

‘Abundance’ is relevant. A large and generous spirit shines through these poems and delights in (or is appalled by) the details of ‘The World We Live In’, the appropriate title of the first of three sections in the collection. For Rodriguez is, in the best sense of that term, a ‘worldly’ poet. However large or modest the theme of a poem may be, it is grounded in the local, in detail of the here and now, the sensory world of light and sound in which we live and move and have our being.

Yet if the local is sometimes simply to be enjoyed for its ‘thinginess’, its oddity or beauty, it is more often imbued with a sense of its place in time, in history, in the political world where power makes itself manifest, often unpleasantly. So, in ‘Epics Enacted in Cloud’, the sight of a plane crossing the violence of a stormy sky is imbued with the violence of history, and it is not just metaphorically that ‘The sky of threat / rushes to a knot’, since clouds literally (but innocently) carry the detritus of willed human destruction. The poem concludes: ‘Hiroshima? Chernobyl? This is a view from the tower, out. / Not seasons’ chemistry set cloud to murder the planet.’

Rodriguez understands the paradox of energy, its Janus face of vitality and destructiveness. Energy is indeed one of her own qualities: of language, opinion, action, but she is engagingly aware that it can get out of hand domestically as well as on a wider scale. So she tells against herself the story of ‘Venetia’:

... who with perfect courage let me paint

her London ceiling with violent

unshiftable Dulux

(a case of only my boredom with

well-sized plaster)

Judith Rodriguez (photograph via the Bellingen Writers Festival)

Judith Rodriguez (photograph via the Bellingen Writers Festival)

The poems in the first section seem a long way from such a domestic scene. Here we are in the ‘great’ world of Hiroshima and Chernobyl, of the Holocaust, dispossession, guerilla warfare, terrorism, and cruel indifference; the world where the barb of injustice ‘turns and festers’, breeding ‘a monstrous updraught of hate’. And yet we do inhabit that world domestically. We live individually in a world that ‘goes horrified to bed and rises horrified’. Sleeping, we suffer the bad dreams brought by the world’s news:

Then there’s the bed-size morass

between the news and day.

No matter that there fluttered

a tender gathering of small clouds

high over the shredded plane-trees.

South Africa is burning awake

screaming in the obscene necklace

Australians, too, inhabit and bear responsibility for that kind of world, as the group of Boat Voice poems reminds us. In an evocation of Yeats’s memorable phrase ‘a terrible beauty is born’, ‘Siev X’ weaves into its text the words of a survivor from that ‘certain maritime incident’:

Like birds floating on the water

the drowned children wash up|

on the mind’s beach.

...

Each night floods our shores

with their sodden wings.

Here is a world in which the poet’s language must speak to give voice to silenced beings, especially those whose life itself has been a defiance of horror – the vanished diplomat, ‘Wallenberg’, the imprisoned Uyghur writer present at the 2014 PEN International Congress only as an image:

He looks at me. The word after his last

written word

struggles to breathe between us.

He looks at me, silenced. The world’s

voices die.

He is an image on cardboard placed

on the chair

where the man would have leaned

crossing his legs, riffling his MS,

smiling a little,

live, a man of words ready to read.

If such figures provide a bastion against the world’s horrors, so too do friends. A capacity for friendship resonates throughout the final section, ‘Celebrations’. For Rodriguez is by no means given over to grimness. She is often wryly comical, and if many of the poems in this section are elegies, what the remembered dead bring her is ‘somehow laughter from beyond’, and the poems perform that restoration of the lost to the light of the present that her friend Gwen Harwood saw as a major purpose of poetry. ‘Out of time, in mind’ concludes ‘The Reading: In Memory of Shanti Devadasan’, a poem that not only draws together many of the themes threaded through The Feather Boy, but also serves as a declaration of poetry’s role as it celebrates reading Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night with Devadasan in a shopping mall in Chennai:

Guttering years cannot blur or stow

in the dark

that reading. Teachers after Chennai

classes

turning pages in Illyria, lady,

among bolts of silk, unroll the beloved

fable of finding the lost, joining the

sundered,

conquering time’s atrocities, contraries

meeting

in sacred joy.

Feather Boy

A feather caught in grass tells of the wind.

It must fill or fall. I am eight,

floating in the lane’s dark flue, the feathers in my fist.War takes me for a man. Up ahead is where

shots rattle like a knocked door

and break off. The men met where they saidare running, we run too, to a shout and its botching.

My knees catapult me

out from the wall’s foot, and my dark chargeslie like spent shells, faces by barely daylight

light enough to find with hand

stretched, then (crouching) cupped from the stir of air –light enough for the feathers I save to betray life.

I am the feather-boy. If I call,

a knife makes sure. And I call, for us crushed in hiding,for all of us scattered, parents, cousins, our fates

feathers in war’s updraft.

Next day in the yard, there’s a farm hand with a messageor a stranger looking too long, strong as my brother,

a man to rot in the wood.

The forest feathers prickle and stoop in my pocket.Judith Rogriguez

‘The Feather Boy’ is based on the account of a Holocaust survivor who was the eight-year-old ‘feather boy’ with a partisan group resisting the Nazi occupation. It is reproduced with kind permission from Puncher & Wattmann.

Comments powered by CComment