- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

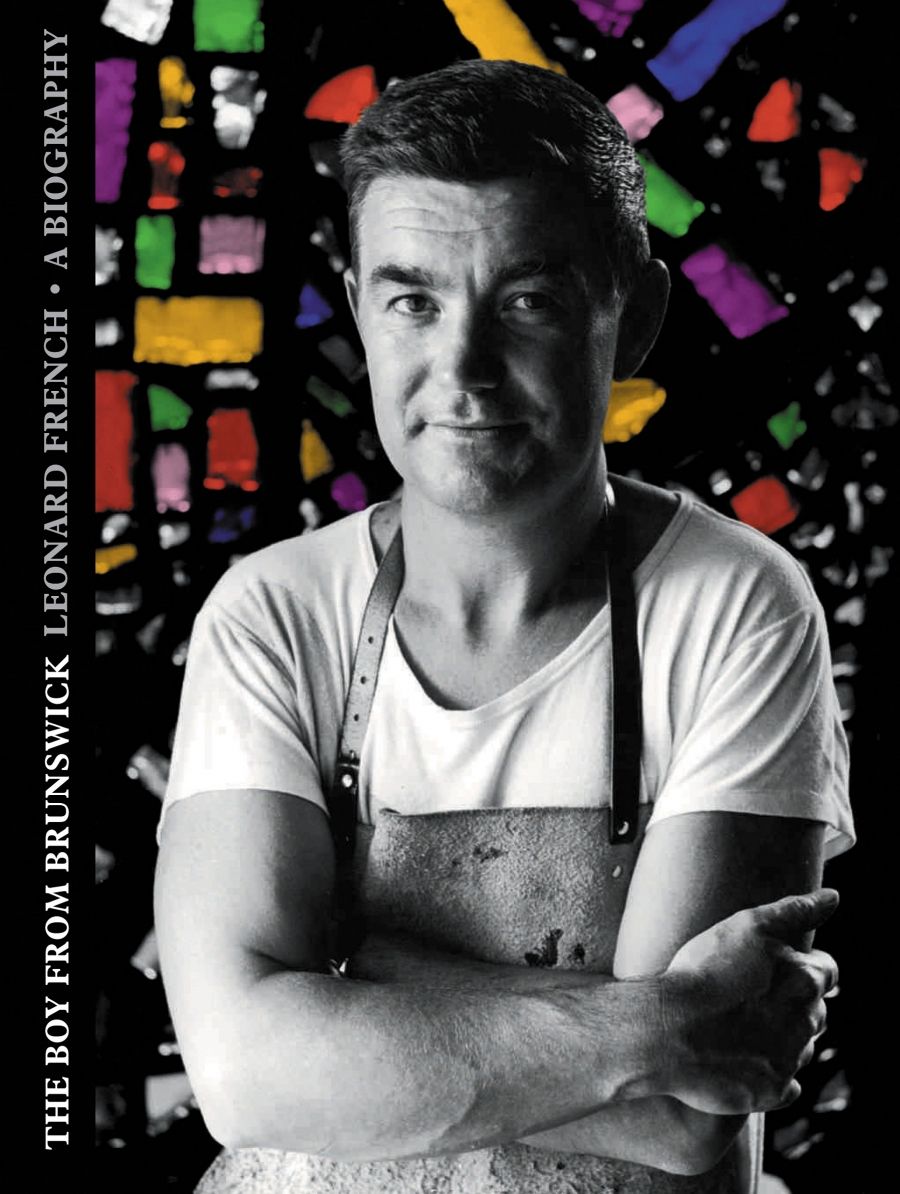

- Custom Article Title: Sheridan Palmer reviews <em>The Boy from Brunswick: Leonard French, A biography</em> by Reg MacDonald

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Old friendships and close collaborations between author and subject can be either a blessing or a curse in biography – a tightrope between discretionary tact and open fire. Both call for intimate but balanced subjectivity, especially where virile egos are concerned. The Boy from Brunswick, a massive tome with sixty chapters and 540 pages, offers a bit of everything ...

- Book 1 Title: The Boy from Brunswick: Leonard French, A biography

- Book 1 Biblio: Australian Scholarly Publishing, $69.95 hb, 540 pp, 9781925801392

Leonard French and Roy Grounds standing under the NGV ceiling on the front cover of LIFE Australia, August 19, 1988, Vol. 45, No. 4. LIFE logo and cover design © TIME inc. Cover photograph by David Moore, courtesy of David Moore Photography © Lisa, Michael, Matthew and Joshua Moore

Leonard French and Roy Grounds standing under the NGV ceiling on the front cover of LIFE Australia, August 19, 1988, Vol. 45, No. 4. LIFE logo and cover design © TIME inc. Cover photograph by David Moore, courtesy of David Moore Photography © Lisa, Michael, Matthew and Joshua Moore

The text, apart from some minor editorial slips, rollicks apace, rounded by evocative passages in which you can smell the turps, envisage the colours, and empathise with the artist’s grinding exhaustion. Still, one wonders what readership the author has in mind. The Boy from Brunswick swings from populist, anecdotal, and potted histories of eminent figures and places to insights into French’s wilful determination and sexist world. Throughout, we observe only too painfully how oppressed women were by men and society: we look back in anger at that postwar era when women were seen as ‘charming’ wallpaper and male chauvinism reigned, particularly in the pub, the élite art world, and beyond. French’s hard-working mother, Myrtle, endlessly battles her argumentative, headstrong son. Len, convinced that he needs to live in order to learn how to be a great artist, leaves his pregnant wife, Joy, and embarks on a postwar grand tour of Britain – courtesy of Joy’s one-way ticket. This pilgrimage is marked by guilt but glitters in the hope of finding universal origins, ancient motifs, and artistic authenticity. Often destitute and unable to send money back to his wife and their newly born twins, he survives a vagabond itinerary while savouring Europe’s modernism, all the while justifying his artistic destiny. On returning to Melbourne, he soon deserts Joy for a talented, ‘feisty’ woman who must play second or third fiddle to her self-absorbed husband.

French’s ambitious, bombastic nature, evident from an early age, drives MacDonald’s ‘heroic’ tone, a kind of reworking of Homeric myths, classics, and a Gulley Jimson morality. The Depression finds an allegory in the Iliad, and his mature professional life in the Odyssey. There is a Dantesque ascent from the pit of suburban poverty as the tenacious young phoenix – or, as we are constantly reminded, the working-class ‘boy from Brunswick’ – rises from the filthy atmosphere of brick factories and the burning stench of landfill tips, scenes set for ‘the making of Len’. A restaging of Genesis befits French’s quest for artistic regeneration and survival with a staggering output to meet proliferating commissions and exhibitions.

While French believed his destiny lay not so much at home but elsewhere, it is Australia’s cliquey and affluent late 1950s and 1960s, abetted by a number of political and cultural mandarins, namely Rudy Koman, H.C. ‘Nugget’ Coombs, Eric Westbrook, and the art critic Alan McCulloch, that made him one of Australia’s most popular and wealthiest mid-century artists. As an emblematic symbolist, French’s passion for classical literary and mythical sources gave his work a universality that transcended local and national trends and, as such, made him an obvious choice for monumental public commissions – the great stained-glass ceiling of the National Gallery of Victoria and windows of the National Library of Australia being two of his more memorable.

MacDonald’s prose is replete with a chauvinistic banality that borders on the offensive. While French’s own crude, expletive colloquialisms and need for ‘male company’ is repeatedly suggested, MacDonald’s parodying of his subject’s insider view of art politics, art friendships, and the art world is often cast in puerile idioms like ‘Not a happy chappie’, or ‘a fair whack of …’, ‘chockful of testosterone’, and galling statements like ‘the incestuous arts community … getting its balls in a knot’, while outrageous alliterations such as ‘The Feisty French Female Line’ grate. Moreover, MacDonald, a former press secretary to Prime Ministers John Gorton and the indiscreet Billy McMahon, informs us that he was privy to major arts-related issues, including how ‘dizzy’ Sonia McMahon was responsible for James Mollison’s appointment as deputy director of the Australian National Gallery in 1971. Pillow talk may have swayed her ineffective husband, but a powerful and assiduous committee of arts people most certainly determined Mollison’s future. Moreover, from numerous published and online sources – McCulloch’s Encyclopaedia of Australian Art (1968) entry on the painter Geoffrey Jones being one example – he takes verbatim extracts without due acknowledgment. Nor should we rely, as MacDonald apparently does, on French for accuracy; the artist James Cant returned to London in 1950, having previously been part of its avant-garde art world in the 1930s, not to study, but because he believed he had a better chance of successfully exhibiting, particularly his commissioned paintings based on Aboriginal Oenpelli cave paintings.

If you can ignore the crass, sexist jargon, this highly informative epic of a unique Australian artist testifies above all else to Leonard French’s passionate commitment to his art and provides interesting insights into Australia’s postwar modernism and art world.

Comments powered by CComment