- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

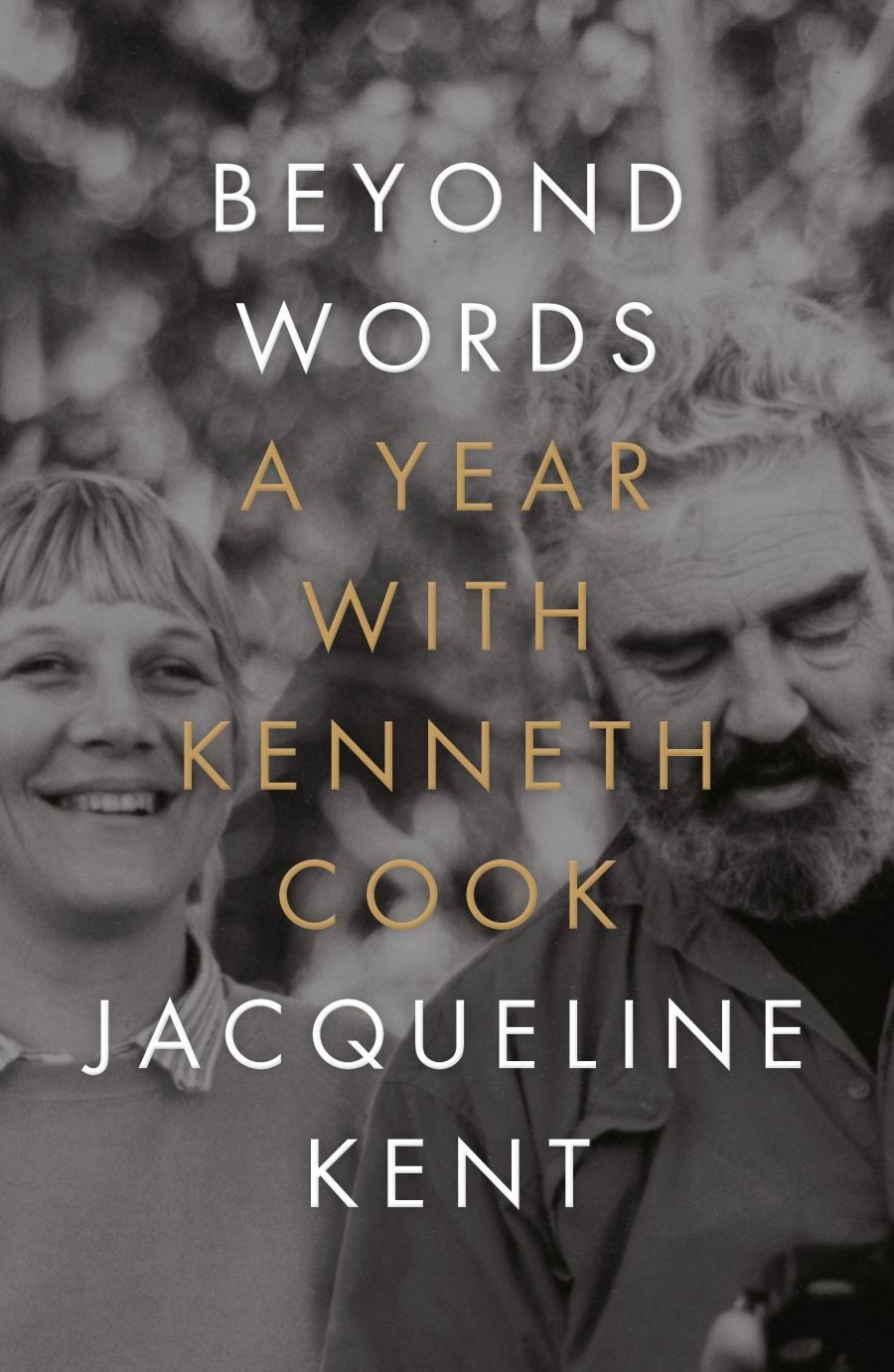

- Custom Article Title: Susan Sheridan reviews <em>Beyond Words: A year with Kenneth Cook</em> by Jacqueline Kent

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Kenneth Cook (1929-87) was a prolific author best known for his first novel, Wake in Fright (1961), which was based on his experience as a young journalist in Broken Hill in the 1950s. In January 1972, as I sat in a London cinema watching the film made from this novel by director Ted Kotcheff, its nightmare vision of outback life seared itself into my brain ...

- Book 1 Title: Beyond Words: A year with Kenneth Cook

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $29.95 hb, 247 pp, 9780702260391

A first-edition copy of Wake in FrightBecause of the success of the film, it has been Cook’s fate to be remembered as a one-book writer. Yet he claimed it was just a story that had to be told, one that he soon left behind in a career that spanned writing novels and stories, journalism, television and stage plays, founding a film production company, speculating in real estate, and running a butterfly farm.

A first-edition copy of Wake in FrightBecause of the success of the film, it has been Cook’s fate to be remembered as a one-book writer. Yet he claimed it was just a story that had to be told, one that he soon left behind in a career that spanned writing novels and stories, journalism, television and stage plays, founding a film production company, speculating in real estate, and running a butterfly farm.

Beyond Words is Jacqueline Kent’s memoir of her intense relationship with Cook, a man twenty years her senior. They had been married only a few months when he died of a heart attack, at the age of fifty-seven, on a road trip in western New South Wales. A ‘lay alcoholic’ (his self-description) and a chain smoker, he had already come perilously close to having a heart attack, and suffered an unacknowledged degree of stress over the end of his first marriage and his bankruptcy.

They met when Kent was employed to edit his comic bush stories, Killer Koala. There was an initial sparring match over the telephone about what this process would involve: ‘Ms Kent … I am not used to being edited. My characters do not exclaim, they do not snort, wince in speech, respond, or chuckle and gibber’. He invited her to what turned out to be a long and boozy lunch. Reading his stories the next day, she was intrigued to find that their humour emanated from the same sensibility that had produced the ‘grimly nihilistic’ Wake in Fright.

They were opposites in many ways. He was a knockabout writer, a man of many enthusiasms, while she was a university-educated freelance editor with literary ambitions. He was a declared bankrupt, an estranged husband, and the father of four adult children, while she was ‘an independent household of one’. They shared political views formed by opposition to Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War. They shared jokes and stories. There was clearly a strong sexual attraction between them. Above all, they shared a life in the literary world in the 1980s when it was the ‘rather lunatic, passionate industry’ that preceded ‘the relatively pinched, cautious literary world of today’.

A still from the film adaptation of Wake in Fright, directed by Ted Kotcheff

A still from the film adaptation of Wake in Fright, directed by Ted Kotcheff

Kent writes of her younger self: ‘It’s very easy to get a name for independence of mind when you don’t really engage with the messiness of life. And this I think is exactly what I had done: I had shielded myself behind a wall of books and a regulated pattern of work.’ The memoir traces the stages by which her orderly life and Cook’s messy one merged, so briefly and dramatically.

At key moments he called the shots, moving their friendship into a sexual relationship, proposing that they leave her tiny, much-loved apartment to buy a new place nearer to his family; deciding to get married; even going on the road trip that turned out to be their last time together. Yet while he challenged the independence she valued so highly, he also admitted to a few uncertainties of his own – about the age difference between them, and whether she would want to have a child. Still, he was not one to talk freely about his earlier life or to exchange the kind of confidences that she had expected; and some of his attitudes – to money, for example, and even to literature – left her puzzled. In a relationship so concentrated into a short space of time, many questions, inevitably, remained.

Since her husband’s death, Kent has made her name as an award-winning biographer – of publisher Beatrice Davis, of musician Hephzibah Menuhin, and, most recently, of Julia Gillard – and has also published a number of Young Adult novels. Turning her hand to memoir, she deftly constructs a narrative that dramatises key moments in their story so that she herself is strongly present, but without making herself the centre of the story.

She creates a vivid sense of the man she loved – his humour, his prejudices, his physical and emotional presence; but also his otherness and the things he hid from her. Regret is inevitably part of mourning the loss of someone deeply loved, and she bravely lists the things she wished she had been able to do: to persuade him to look after his health; to find out more about his life and beliefs; to encourage him to write more novels. All impossible tasks, probably, with the man she has portrayed here – a clever, charming, headstrong, unreconstructed Australian male of his generation.

Comments powered by CComment