- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

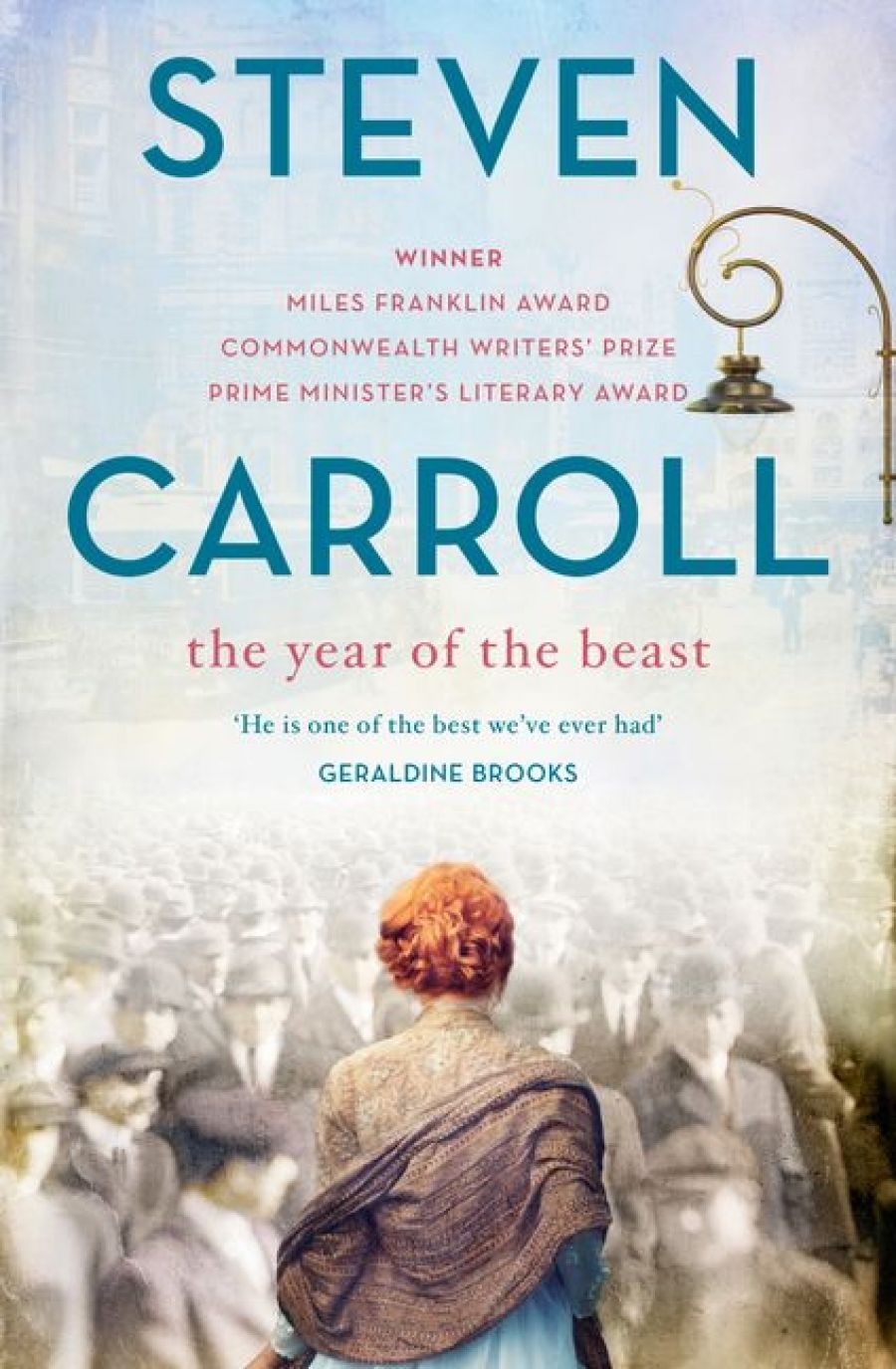

- Custom Article Title: Kerryn Goldsworthy reviews <em>The Year of The Beast</em> by Steven Carroll

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In his 2017 essay ‘Notes for a Novel’, illuminatingly added as a kind of afterword at the end of this book, Steven Carroll recalls a dream that he had twenty years ago. It was this dream, he says, that grew into a series of novels centred on the Melbourne suburb of Glenroy, a series of which this novel is the sixth and last. It was ...

- Book 1 Title: The Year of The Beast

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $29.99 pb, 304 pp, 9781460757697

The opening scene takes place in October of that year, when a woman called Maryanne, a thirty-nine-year-old spinster, pregnant with the child of a country-town German draper who will not marry her, is standing on the edge of a crowd in the Melbourne CBD. The occasion is a street rally about the contentious second ‘referendum’ on wartime conscription (more accurately called a plebiscite since it involved no change to the Constitution) that bitterly divided an Australian society already in a state of collective anxiety and civil unrest.

This first section of the novel is titled ‘Festival of the Id’. In the opening scene, Carroll concentrates more on the crowd than on his main character, musing on the forces behind its ugly, mindless mood and its hovering on the edge of violence. In ‘Notes for a Novel’, Carroll discusses the central importance of Freud’s Civilisation and Its Discontents to his thinking about this novel:

Freud argues, compellingly, that although we may pride ourselves on being civilised … we must suppress the pleasure seeking, anarchic, primal part of ourselves or no cooperative social enterprise can be successful … But every now and then there is a mass outbreak of the primal and the Id erupts into pleasure seeking, death desiring life. For death … is the Id’s ultimate pleasure: that something final that it craves.

The crowd in the Melbourne CBD on an October day in 1917 is the Id made manifest, the Beast of the title, something Carroll proclaims overtly perhaps a little too often. If this novel has a weakness, it is Carroll’s overreliance on a style that has characterised the Glenroy novels: one that relies on repetition of particular words or motifs, which, when overused, come to seem artificial and forced.

Carroll’s style, while not ornate or pretentious, nonetheless has an incantatory or even sometimes biblical quality in its rhythms. This too can become intrusive, with its many declarative sentences beginning with ‘And’. Sometimes there are five or six of these to a page, creating an overly portentous tone that often isn’t justified by the subject matter. Carroll has written about his reasons for using such a style, of wanting to avoid the simple social realism traditionally associated with fiction about working-class people. But having a good reason for a particular stylistic approach doesn’t guarantee that it will always work.

This style is at its most intrusive in the reflective passages, but all of the novel’s scenes of action are focused and intense, and some of them are brilliantly and movingly written. The scene of baby Vic’s conception, which takes place between the illicit lovers in a small teacher’s room at the back of the schoolhouse in a country town, more than fulfils Carroll’s stated ambition of showing the extraordinary beneath the ordinariness of most people’s lives:

‘You look different. Sitting there,’ he said slowly …

‘How? How do I look different?’

‘Schöne,’ he said, almost in a dream. ‘Schöne Frau.’

Such strange-sounding words. The language of the enemy. But wonderful.

Steven Carroll (photograph via The Wheeler Centre)

Steven Carroll (photograph via The Wheeler Centre)

Other precisely imagined and intensely conveyed scenes include: Maryanne’s delivery of a fateful letter to a rich woman’s house; her sister Katherine’s departure after the baby is born; and the horrifying scene in which Father Gheogan instructs Maryanne that she must put herself in the care of the Church and give up her baby to a foundling home: ‘the priest roaring at her like a three-headed dog’. All of these scenes combine a richly cinematic quality with complex interiority.

As with all of the earlier Glenroy novels, this final one concerns itself with the ominpresence of history in our lives: with time and its loops and folds in the connections between past and present. The whole six-part family saga unfolds from that moment in the back room of the schoolhouse where Maryanne is called beautiful in a foreign language by a man who never comes to know his son. Like many of his contemporaries in real life, Vic is, in a sense, sui generis: a child not of easily traceable lineage either humble or noble, but rather of the new country itself.

Comments powered by CComment