- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

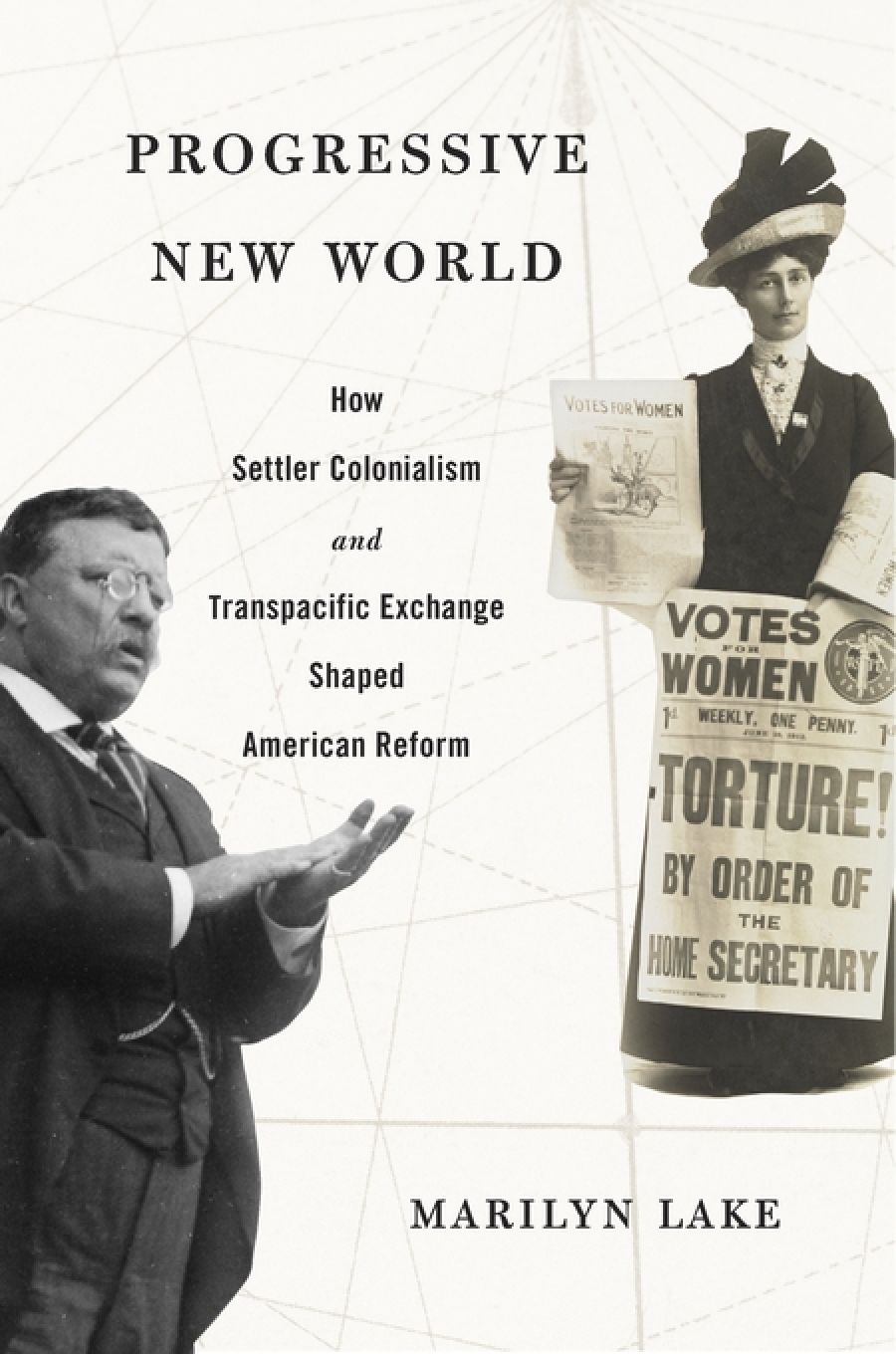

- Custom Article Title: Ian Tyrrell reviews <em>Progressive New World</em> by Marilyn Lake

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1902, Australian feminist and social reformer Vida Goldstein met Theodore Roosevelt in the White House during her North American lecture tour. Marilyn Lake retells the story of their encounter in her important new book. Seizing Goldstein’s hand in a vice-like grip, the president exclaimed: ‘delighted to meet you’. Australasian social and economic reforms attracted Roosevelt and other Americans ...

- Book 1 Title: Progressive New World

- Book 1 Subtitle: How settler colonialism and transpacific exchange shaped American reform

- Book 1 Biblio: Harvard University Press (Footprint), $68 hb, 307 pp, 9780674975958

Australia and New Zealand became known from 1890 to 1920 as a legislative ‘laboratory’ through social ‘experiments’. Foundational to Australian reform, White Australia and tariff protection were ‘closely watched by reformers in the United States’. Arbitration, women’s voting rights, hours and conditions of work, and indeed every question on the intervention of the state in the economy and society saw Australasian innovations being highlighted. Progressivism for Lake equals primarily democratic reforms and social justice, but with a racial underpinning. American historians still dispute the term’s coherence, meanings, and efficacy, but most would concede that, in ‘Progressivism’, efficiency was a third pillar of the diverse and changing ‘movement’ after 1900.

It was not just Americans who found antipodean reform intriguing, but Lake does not assess this multinational curiosity. Instead, she treats Australasians and American reformers as having so much in common that their interactions can be considered apart from larger transnational circulations. What made the trans-Pacific exchange distinctive was a self-conscious fashioning of New World democracies seeking to throw off the trammels of old Europe; but simultaneously both sides of the exchange were settler-colonial states that supressed and marginalised the original inhabitants to achieve Progressive ambitions.

The first theme, trans-Pacific links, has been covered before, but rarely if ever with Lake’s meticulous attention to gender and the sequences of personal communication. Australian views solidified in the 1880s and 1890s as Federation beckoned. Reciprocal influences are documented, and the flow east across the Pacific is stressed, though Lake shows how the Australian constitution bore marks of the American, notably through transnational networks stimulating Andrew Inglis Clark’s interest in federalism.

Australasian reform was usually in advance of the United States. Lake acknowledges that antipodean impacts upon the latter were often subtle or circuitous. The Sheppard-Towner Act (1921) on child and maternal health and welfare was ‘anticipated’ by Australian experiments. Path-breaking use of sociological data in wage determinations, as in Muller v Oregon (1908) to support a minimum wage, similarly revealed in a subterranean way Justice Higgins’s preoccupations in the Harvester judgment (1907).

Lake explains why the complicated US Constitution made Australasian social democracy hard to copy. (Indeed, Sheppard-Towner was struck down by the Supreme Court in 1927.) By the time significant US social democratic measures were enacted federally it was the 1930s, and the context was more Atlantic-centred than Pacific. Moreover, many American democratic measures, like city management and citizen initiative laws on referenda and recall of state officials, are not discussed, while others that are, like proportional representation, had limited impact stateside.

The treatment of settler colonialism is Lake’s most arresting contribution, and yet it raises contextual questions. American historians have mostly shied away from the concept. Margaret Jacobs, perhaps the best-known American practitioner in the field with comparative interests, notes how many scholars see it as a ‘fad’. Yet Lake builds upon Jacobs and the phalanx of Australasians working on settler colonialism to demonstrate the idea’s relevance to state formation. The marginalisation and discrimination concerning the indigenous was, Lake argues, the dark underbelly of Progressivism. That movement as a whole sought to advance the interests of whites, including women, and this came at the expense of American Indians. At most, Progressives tended to favour indigenous (and other ethnic) cultural assimilation, a process that amounted to fulfilling Patrick Wolfe’s idea of a ‘logic of elimination’ in settler colonialism. But Lake notes that certain forthright Progressives, mostly women, spoke on behalf of indigenous people. In her final chapter, Lake gives voice to independent indigenous protest, and draws parallels between movements across the Pacific seeking to combat Progressivism’s assimilative nationalism.

Marilyn Lake (photograph via the University of Melbourne)Applying settler colonial analysis must confront the different world-historical position of each country. The two reached divergent developmental stages, and Theodore Roosevelt sensed the trajectory. When Pearson visited the United States in the 1860s and when Deakin toured in 1884–85, it was possible to see a white settler correlation. By 1900, however, the United States was transitioning from a settler-colonial polity to a nation-empire in which the frontier of settler colonialism was displaced into national and global struggles over the distribution of resources. Progressives pitted not whites against American Indians but Progressive reform against big economic interests that, Roosevelt stated, gained control of land, forests, and mines at the expense of ‘the actual settler’. The latter’s survival Progressives saw as securing the republic’s moral, demographic, and economic footing. Indians were collateral damage in this process. Progressives did not initiate American Indian assimilation, but the paternalistically inclined among them, like Roosevelt, could offer only a brake on corrupt and inefficient nineteenth-century allotment policy that began depriving American Indians of tribal land in the name of competitive individualism and republican citizenship well before the Civil War.

Marilyn Lake (photograph via the University of Melbourne)Applying settler colonial analysis must confront the different world-historical position of each country. The two reached divergent developmental stages, and Theodore Roosevelt sensed the trajectory. When Pearson visited the United States in the 1860s and when Deakin toured in 1884–85, it was possible to see a white settler correlation. By 1900, however, the United States was transitioning from a settler-colonial polity to a nation-empire in which the frontier of settler colonialism was displaced into national and global struggles over the distribution of resources. Progressives pitted not whites against American Indians but Progressive reform against big economic interests that, Roosevelt stated, gained control of land, forests, and mines at the expense of ‘the actual settler’. The latter’s survival Progressives saw as securing the republic’s moral, demographic, and economic footing. Indians were collateral damage in this process. Progressives did not initiate American Indian assimilation, but the paternalistically inclined among them, like Roosevelt, could offer only a brake on corrupt and inefficient nineteenth-century allotment policy that began depriving American Indians of tribal land in the name of competitive individualism and republican citizenship well before the Civil War.

The Fairfax newspaperman Samuel Cook of Marrickville was neither well-known nor a self-identified ‘Progressive’. Travelling home from Britain in 1907, he visited the White House and, like Goldstein, ‘had a most interesting interview with President Roosevelt’. Whether Roosevelt welcomed every Australian approaching his office is surely doubtful, but he seemed as ‘delighted’ to see Cook as anybody, ‘showed a great interest in Australia, and expressed his gratification at its success and progress’, the Sydney Morning Herald reported. Arbitration was discussed, but the most telling moment was Roosevelt’s asking Cook why Australians still called themselves colonials. The unstated assumption was that Americans were not. Cook protested, but the question suggests that Roosevelt understood how trans-Pacific Anglo-Saxons already had a materially and conceptually unequal relationship – and future. American and Australian literary and political élites espoused a certain Anglo-Saxonism, but the American version after the Spanish–American War (1898) assumed a coming US takeover within the Anglosphere, and the need to strengthen the imperial state internally to compete with rivals Germany and Japan.

Thereafter, Progressivism’s egalitarian potential was increasingly deflected towards strengthening the state through efficiency, that other, neglected leg of Progressive reform. As for trans-Pacific links, Americans all evinced ‘the liveliest interest’, Cook remarked, but they ‘did not know much about Australia’.

Comments powered by CComment