- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Non-fiction

- Subheading: Stella Lees reviews Robyn Annear, Dyan Blacklock, Jacqui Grantford, and Karl Kruszelnicki

- Custom Article Title: Four young adult non-fiction books

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Four young adult non-fiction books

- Article Subtitle: Stella Lees reviews Robyn Annear, Dyan Blacklock, Jacqui Grantford, and Karl Kruszelnicki

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

As Eric Hobsbawn points out in his autobiography, Interesting Times: A Twentieth Century Life (2002), ‘the world needs historians more than ever, especially skeptical ones’. History, however, is not a popular subject in today’s schools. Three of these four books make attempts, variously successful, to engage young readers in a sense of the past. The other is a bizarre compilation of odd details, and could be considered an account of the history of certain sciences; it almost fits into the historical ambit.

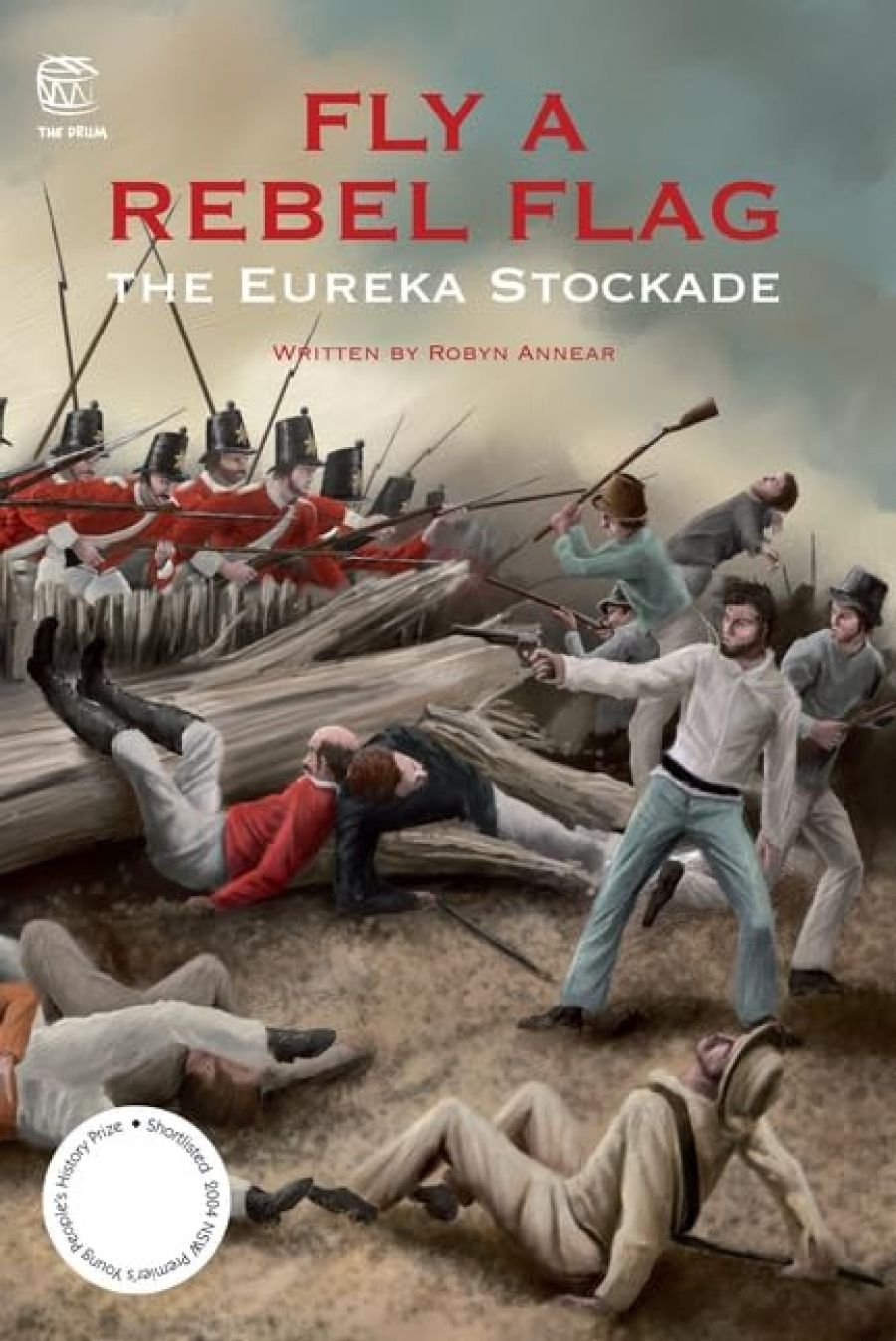

In Fly a Rebel Flag: The battle at Eureka (black dog books, $16.95 pb, 149 pp), which is aimed at children aged ten or older, Robyn Annear has taken the Eureka uprising in 1854, a twenty-minute battle in Ballarat that changed Australia forever, she says. Annear looks at the sources of the conflict, such as the thirty-shilling licence fees (equivalent to $200 in today’s money), the peremptory way in which it was collected from people who still could not vote for the government that instituted it, and the Ballarat Reform League. She is particularly interested in the people who were involved: not just Peter Lalor, Raffaello Carboni, John Basson Humffray, Frederick Vern and George Black – the rebel leaders – but also Captain Charles Pasley, government engineer and military officer, Major-General Sir Robert Nickle, commander-in-chief of military forces in the colonies, Governor Sir Charles Hotham, Robert Rede, gold commissioner, and many lesser mortals.

Annear puts the reader in the participants’ shoes: what it was like to be hounded by the police; the difficulty of finding enough gold to enable the digger to survive; the confusion of the battle; the trial of the first of the thirteen rebels, who were charged with ‘four acts amounting to treason’. Annear, always working from primary sources, treats her young readers with respect. She untangles many of the stories surrounding the rebellion, such as the fire at Bentley’s Hotel, the role of the Creswick diggers, and the part played by the Ballarat Times. She looks to what was happening in the world outside the Colony of Victoria – Chartism, the Irish Famine, the ‘spirit of resistance’ abroad – and does not shrink from the bloodiness of the battle. There is surely no better book for young readers about the Stockade than this one. For apprentice historians, it is a model of research, presentation and interpretation.

Dyan Blacklock’s The Roman Army (Scholastic, $29.95 hb, 46 pp), strikingly illustrated by David Kennett, is less holistic. It looks at the means by which the Romans (‘the greatest fighting force the world has ever known’) ruled the world. The personnel of the army, the weapons they perfected, and the bridges and roads they built to carry the force are described in detail. Illustrations abound, presented in a harsh, structural style using bold pen and bright acrylic, matching the determination and discipline exhibited by this military machine.

But history is more than facts. The Roman Empire stretched from Syria to Britain. Why did Rome send her young men to die at the hands of Celt or Gaul, Numidian or Parthian? What are the legacies of this force? The Roman way of subjugation was pre-eminent until a preference for guerilla tactics defeated the contemporary world’s greatest fighting force in Vietnam. What happened to the vanquished? Some attention is given to the immediate pillage and murder that followed defeat, but none to the long-term results of Roman occupation. Such questions are not addressed: this is not a history book so much as a reference for the young autodidacts who become obsessive collectors of information (often about quite esoteric subjects). Perhaps in the school classroom it could offer a way in to the ‘why’ of history.

Nevertheless, The Roman Army is serious stuff, which cannot be said about Jacqui Grantford’s Shoes News (Lothian, $26.95 hb, [32] pp), which is virtually anti-history. We start with prehistoric times, as the Neanderthal struggle with the ugh boot. The Olympic Greeks eschewed footwear, it seems, allowing the army’s worn-out shoes to be repaired every four years; Newton’s falling shoe was historically mistaken for an apple; the moon landing was apparently aimed to test zero gravity on ripple soles. Those pictures of Egyptians standing on one foot halved the need for sandals. The Mona Lisa was merely admiring her new shoes. It is likely to be hilarious if you are about ten, a good reader and have some scraps of knowledge about history. This one’s for the young absurdist, so it’s all carried to the ridiculous, but that’s the point. After age ten, the laughs may be infrequent as Grantford stretches it to inanity.

Karl Kruszelnicki’s Bumbreath, Botox and Bubbles (HarperCollins, $24.95 pb, 246 pp) is not absurd but uncomfortably realistic. Number five in the ‘New Moments in Science’ series, it informs you about items such as the causes of champagne bubbles, how the Indian rope-trick works, who invented the pap smear test, why birds in flight don’t collide etc. As you may gather, this is for the older reader, with some details many of us may rather avoid. There’s a whole chapter on the right way to kiss, if you don’t happen to know already, and a lot of nasty stuff about smelly breath. It also describes how to resuscitate a man through his penis. Kruszelnicki is a true sceptic. He accepts nothing as given in his search to discover the facts. Bumbreath, Botox and Bubbles is told in his customary style, with scientific accuracy not sacrificed to laughs, but the laughs are there through lots of asides, cartoons, statistical surprises and irony. It would be a winning gift for a thirteen- or fourteen-year-old ready to question everything.

Comments powered by CComment