- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Against the Clock

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1936, at the Nazi Olympics, Jesse Owens won four gold medals and the hearts of the German people, but when he returned to the US his main aim was to turn Olympic gold into real gold. At Mexico City in 1968, Tommy Smith and John Carlos threw away their own careers by appearing on the victory podium barefoot and gesturing with the Black Power salute in protest against the treatment of their ‘brothers’ in the US and elsewhere. Television sent the Smith–Carlos message around the world, but earned the two athletes more opprobrium than praise in Western nations that were still coming to terms with the cultural revolution of the 1960s. This was before the Moscow Olympics in 1980, when the democracies could still convince themselves that sport and politics were worlds apart and should never mix.

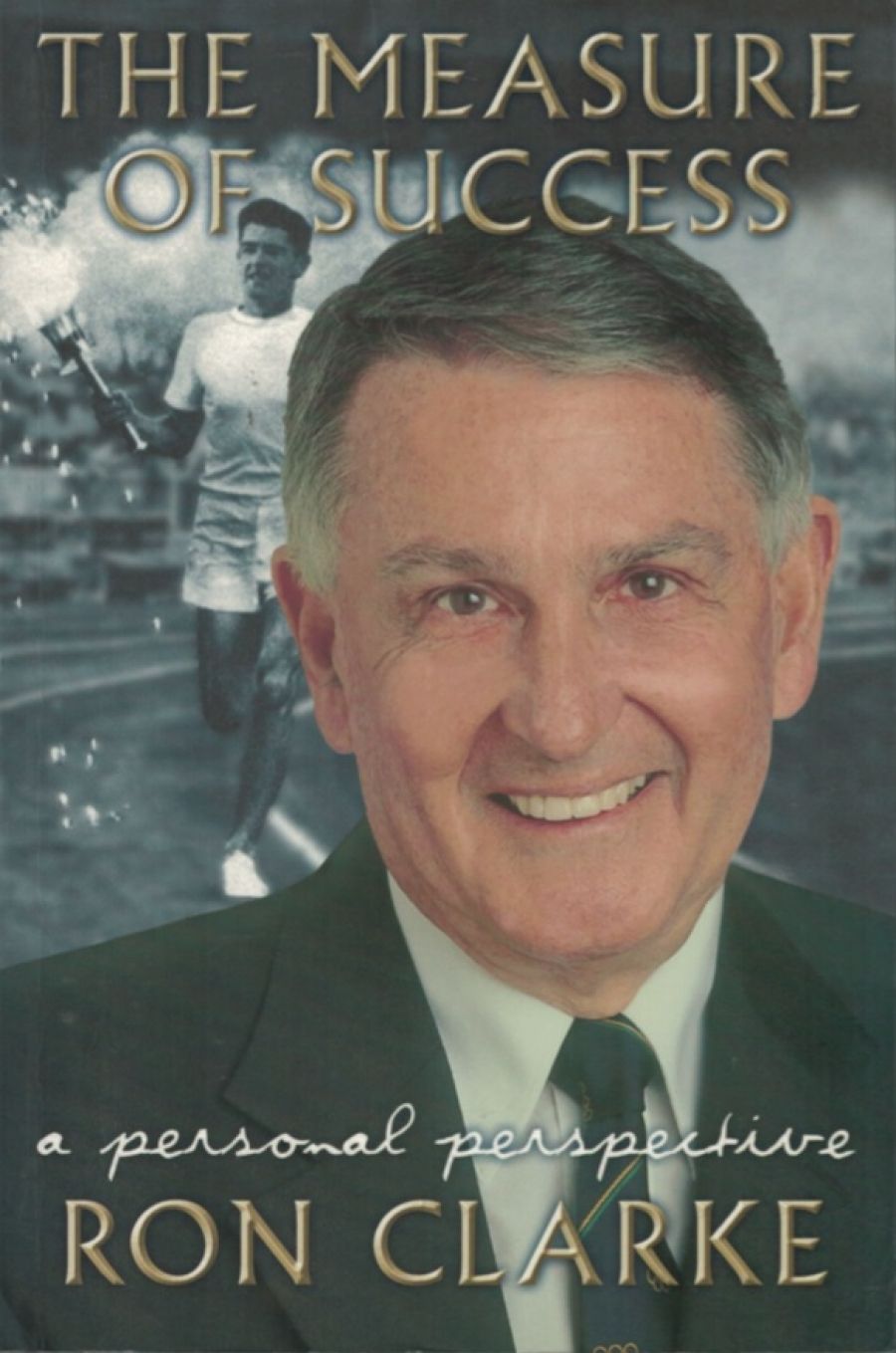

- Book 1 Title: The Measure of Success

- Book 1 Subtitle: A personal perspective

- Book 1 Biblio: Lothian, $34.95 pb, 299 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

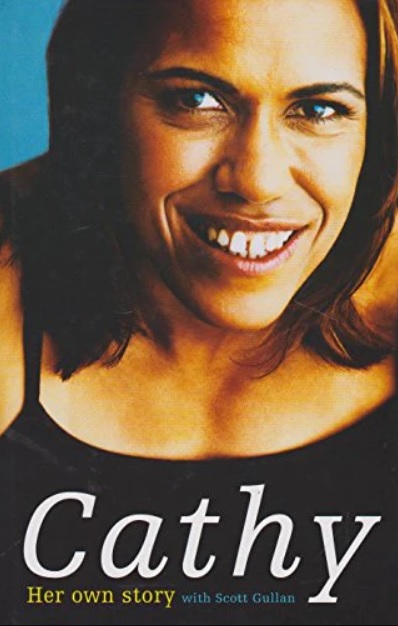

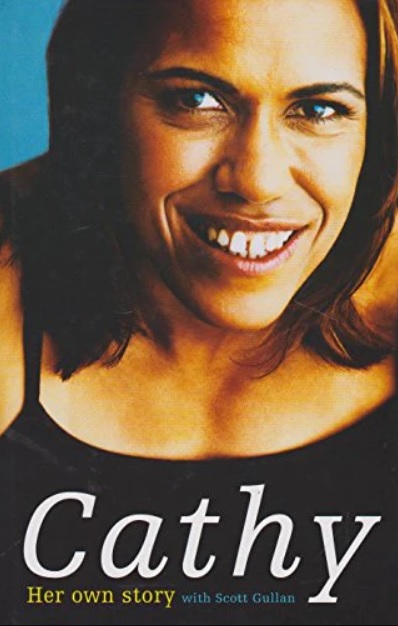

- Book 2 Title: Cathy

- Book 2 Subtitle: Her own story

- Book 2 Biblio: Viking, $45 hb, 395 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

At the 1994 Commonwealth Games in Victoria, Canada, the rising young Aboriginal star runner Cathy Freeman proudly carried the flag of her black nation around her shoulders after winning gold in the 400 metres. Unlike Owens in 1936, she used her position to make a statement on behalf of her ‘people’, but, unlike the reaction to Smith and Carlos in 1968, her gesture was largely applauded by most Australians. Prime Minister Paul Keating sent her a message of congratulation that was more in the spirit of public opinion than the spluttering disgust of Arthur Tunstall of the RSL. Cathy went on to further successes, none greater than her gold medal in the 400 metres at the Sydney Olympics in 2000, a triumph over unconscionable media pressures. She was named Young Australian of the Year in 1991 and Australian of the Year in 1997.

Ron Clarke never won a gold medal in a career that saw him gain five Commonwealth silver medals, one Olympic bronze and nineteen world records in an eight-year period. He is best remembered as the young athlete who was nearly barbecued when he lit the Olympic torch to open the Melbourne Olympics of 1956; indirectly as the athlete who famously fell while leading the field at the Australian Championships at Olympic Park in 1956, forcing John Landy to jump over him (and spiking him in the process). Clarke is often known as the athlete who kept coming second, but he was cruelly deprived of gold at the Mexico Olympics by the altitude and by administrators who made no concessions to distance runners whose normal training was done at sea level.

Clarke and Freeman came not only from different social backgrounds but from sporting worlds separated by the changes from the 1960s that overturned the last remnants of amateurism and the victory of commercialism in sport that arrived with the global reach of television in the 1980s.

Clarke came from a modest background, a sporting family from one of Melbourne’s less affluent suburbs, and a state school education that he looks back on fondly. He went on to become a millionaire with the same self-discipline and drive that made him a world-class sportsman. Unlike most self-made millionaires (and successful sports stars), he has spent the latter half of his life trying to give away his money.

Freeman, we hardly need reminding, was an Aboriginal child from northern Queensland, her mother the daughter of a ‘stolen’ child, her father a rugby star who fell victim to the drink, her stepfather a white follower of the Batha’i faith, who first noted the precocious talents of young Cathy and ensured that they were nurtured in the best possible way by turning her over to experts. Cathy left all her business affairs to Nick Bideau, her coach, partner and business manager, but even during the nasty squabbles that came with their tempestuous break-up, it is never clear where her millions came from. Perhaps she never really knew. Freeman tells her story honestly, including the fiery relations with those around her, particularly the two older men who were her lovers, and the troupe of coaches, personal assistants, masseurs and others who are an indispensable part of the travelling circus of today’s superstars.

Clarke probably made even more money than Cathy, but none of it came directly from his globetrotting athletic career. In the years before he took up athletics seriously, in December 1961, Clarke had already shown himself to be an astute businessman, but his contacts in sport helped launch him into new opportunities, above all with Horst Dassler, the financial genius behind the transformation of the world’s two largest sports institutions – the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and FIFA, the international body controlling association football – into the massive commercial conglomerates that they are today. Clarke’s assessment of Dassler is rosier than that of Andrew Jennings and other critics of the IOC. While Clarke notes the dark side to Dassler, he is easier on him than he is on others who enriched themselves through commercial sport.

Clarke has chosen to write his story without the aid of a ‘ghost’; in Scott Gullan, Cathy has found a writer who seems to have captured her mood swings and hopes and fears, the ‘panic’ and ‘confusion’ that at times threatened to overwhelm her free-spirited soul, but also the sheer euphoria of running. Clarke writes in a businesslike way, partly about sport, partly about business, but also about those who have influenced him, at times rather cloyingly when it comes to his family. But even when discussing his running, Clarke gives the impression of a methodical approach to training sessions that leaves you wondering when he got the time to make his businesses such successes. The same might even be said of his domestic arrangements.

For Clarke, sport came second to business. National service spoiled his chance of competing at the Melbourne Olympics (athletes were not granted the dispensations given to Australian Rules footballers), and it was not until he was in his early twenties that a smashed finger put an end to participation in his first loves, Australian Rules and cricket, and directed him to the sport at which he would excel. For Freeman, running was her life. At fourteen years of age, she told her teacher her goal in life was to win gold at the Olympics, and from then until 2000 in Sydney she collected the gold medals that eluded Clarke. Clarke claimed consistency as his trademark and lacked the predatory instincts that made Cathy the world champion she became: ‘Running against the clock I’m not good at; hunting down other people is what motivates me.’

Both Clarke and Freeman were devoted to their families. Clarke idolised his older brother, Jack, a greatly respected sportsman in his own right, mainly as a footballer with Essendon in the Victorian Football League. As in his relations with his wife and parents, never an angry word passed between Clarke and any of his close family: his father’s silent rebuke for not walking in a Victorian junior cricket match when he was caught behind wicket was lesson enough. Such stoicism was not to be found in the Freeman household. Cathy never forgot her older sister, Anne-Marie, born with cerebral palsy and who died in her early twenties, and loved her mother, whose words inspired her to make the most of her abilities: ‘Look, you know your sister can’t walk, can’t talk, she can’t do all the things that you can. You’ve got two good arms and two good legs, now go out there and use them.’ She also had a deep affection for her brothers and her nieces and nephews with whom she shared all her triumphs. She includes the reference to them having the ‘biggest smiles I’ve ever seen and they are not even drunk’ that was deleted from Channel 7’s repeats of the interview after her victory in Sydney. It was not unusual for seventeen of the Freeman clan to turn up at Cathy’s Kew home for Christmas.

Clarke believes that Australia ‘is a fantastic country’, but he, like most Australians, has not had to endure the racism suffered by Cathy as a young black woman. She does not dodge the race issue here. Unlike Evonne Goolagong, who chastised those who wanted to use her to bolster the cause of their ‘people’, she has sided with them without getting too involved. Her parading of the Aboriginal flag and her pride of place at the opening ceremony of the Sydney Olympics were triumphant celebrations of reconciliation. Unfortunately for Cathy, it seems that, having reached the pinnacle of fame, the fire left her soul, and her book ends with a sad question mark.

Clarke frequently refers to his ‘blessed’ and ‘lucky’ life, and it does seem to have been one in which virtue would have been its own reward, except that he kept on making more and more money. If Cathy’s life had an inevitable political tinge to it, so too does Clarke’s, for here is the smiling face of capitalism, the appeal of a man who in sport detested the ‘winning is the only thing’ mentality and who, in business, appealed to the same ideals. Clarke rails against the selfishness of his fellow millionaires with the same acerbity he employs to criticise the administrators of the sport he loves, above all at the IOC and the Australian Olympic Committee, especially for the latter’s role in blighting the careers of young swimmers in the wake of the Dawn Fraser controversy at Tokyo in 1964. Clarke is in a good position to speak. Like Freeman, he completely rejected drugs. Indeed, he was severely reprimanded for speaking out about the use of steroids as early as 1964. In business and as a philanthropist, he has been a paragon of decency.

Two individuals, two vastly different lives and eras, drawn together by the sheer joy of sport – a pursuit, as both show, that is not as trivial as some would have it.

Comments powered by CComment