- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A Luminous Cocoon

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In Across the Magic Line: Growing up in Fiji, Patricia Page comes full circle, returning with her sister Gay after an absence of fifty years to the enchanted islands of their childhood, reliving their memories and examining the very different Fiji of the present. Despite changes everywhere, the astonishing beauty of the islands remains, and the kindness of the Fijians is constant.

- Book 1 Title: Across the Magic Line

- Book 1 Subtitle: Growing up in Fiji

- Book 1 Biblio: Pandanus, $34.95 pb, 272 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Within the narrative, Page builds, bit by bit, a comprehensive history of Fiji. Coming to us in snatches, as part of her personal story, it is easily absorbed. Much of her account of pre-colonial Fiji comes from Life in Feejee: Five Years among the Cannibals, by Mary Wallis, the wife of a bêche-de-mer captain trading out of Salem, Massachusetts, who kept a diary of her Fijian visit in the 1840s. Add to this the sensational stories of an old lady who, rightly or wrongly, recalled ‘a group of Fijians go by, carrying bunches of human arms and legs on a pole’. There are tales of the great war canoes – triumphs of the boatbuilders’ craft – launched by warriors over the living bodies of their enemies. Ritualised cannibalism involved torture before death: the slicing off and devouring of body parts in front of the victim. When the chiefs died, their wives were ceremonially strangled so as to accompany them on their way. Page tells of the early incursions of shipwrecked sailors, missionaries, blackbirders and sandalwood traders, most intent on rape and plunder. Cakobau, the king at the time of Mary Wallis’s account, ceded Fiji to Queen Victoria to put an end to the exploitation of his people. When he converted to Christianity, they followed en masse, effortlessly transferring their enthusiasm for human flesh to a somewhat similar fervour for religion.

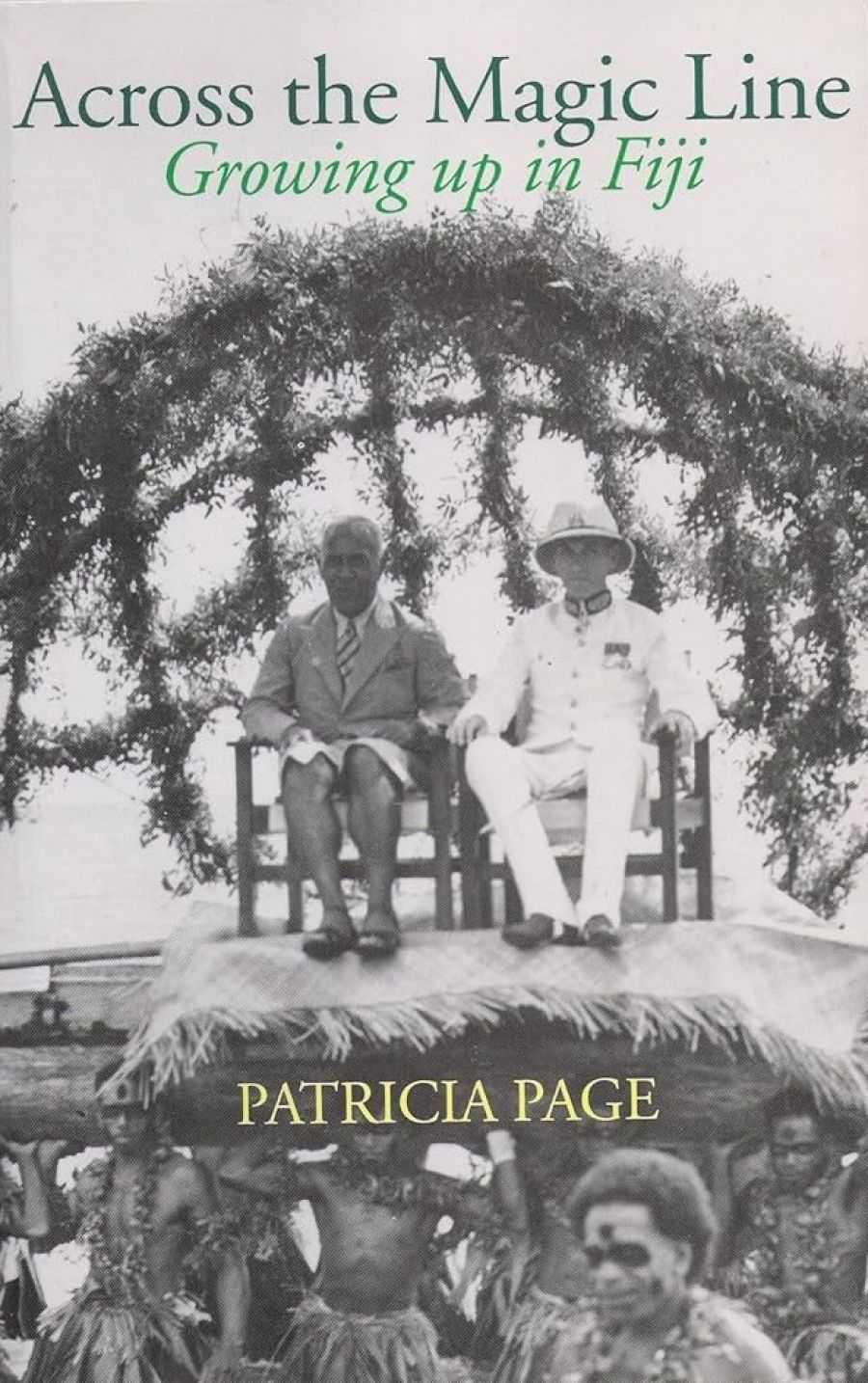

Page details the complications of Fijian society in the 1940s. Each island or district had its own intricate hierarchies, both British and Fijian: the District Commissioners and junior officials, the ‘Ratus’ or chiefs, the ‘Bulis’ or sub-chiefs. At the head of all was the governor, the representative of British power. His pith helmet was topped by billowing ostrich plumes, and his comic opera uniforms were accessorised with white gloves, a carved gold-tipped stick and a sword in an engraved silver scabbard. The picture on the cover tells it all. Page also examines the racial hierarchy of white, mixed-race (a ‘touch of the tar-brush’), the Fijians who by law owned the land, and the Indians – originally indentured labourers’ – who leased and worked it. Page traces this racial divide through to the two Rabuka coups and the more violent insurrection led by George Speight. Perhaps she is disingenuous when she suggests that there was little animosity, on a personal level, between the Indians and Fijians.

Her childhood memories of Fiji were so intense that, in the intervening fifty years, they formed a ‘luminous cocoon’ in her imagination. Previously an insecure and fearful child – ‘I felt perched on the edge of the planet, about to fall off’ – in Fiji Page found her identity, her ‘place in the universe’. Life was free and easy, full of adventure and discovery. Schools were closed because of the war, and Suva became a vast playground for the children, who ran wild among the vacant plots, taro plantations and ravines hung with creepers, seeking out one another regardless of race. They were oblivious to danger, even though the Japanese occupied the Solomons and the Gilbert and Ellice Islands. Many families were evacuated and there were curfews, checkpoints and blackouts. The occupying US troops offended the establishment by carousing and by treating the Fijians as equals. Quite the most poignant episode in the book is the farewell to the Fijian Battalion as they leave to fight, with outstanding bravery, alongside the Americans in the Solomons.

Against this background there is the family history of an adventurous father who thought nothing of taking his family to Fiji in wartime, with a minesweeper ploughing on ahead to clear the ship’s passage. The mother has experienced her own tragedies, in particular the birth and death of a retarded child. Page’s return to Fiji brings a number of personal surprises, in particular the probability that her mother had had an affair with a rakish sea captain. John Cummings, Patricia’s first love, has had a gender reassignment. He presents fifty years later as a stylish and confident woman who doesn’t even remember her. There are many other changes: in place of the staid and pseudo-British hotels of her childhood, Page surveys the vast resorts of the Coral Coast and, at Pacific Harbour, a Disneyland-like theme park of Fijian history. Fantastic ‘bures’ – such as were never seen in the villages – add ‘authenticity’ to the resorts, but the Fijians prefer weatherboard or concrete blocks with tin roofs. Nevertheless, the sisters rediscover their own authentic Fiji. Page takes us on an enticing journey through its out-of-the-way places, complete with Technicolor descriptions of the scenery.

Across the Magic Line is history, memoir, travel literature and more. Perhaps it attempts too much. The last hundred pages could have been compressed, and a few minor inaccuracies (for instance, the date of Empire Day – May 24, Queen Victoria’s birthday) corrected. Still, this is an enthralling book for those who want to know more about the Fijian Islands, as they were and as they are.

Comments powered by CComment