- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Carlton Forever

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When is a suburb not a suburb? When it is an inner-urban locale with a distinctive café culture, its own postcode and football team, but no town all. And here’s another: how did an Old English word meaning ‘churl’s farm’ come to be assigned to a swanky inner suburb of a major city in the southern hemisphere? These and numerous other questions are answered in Carlton: A History. This encyclopedic book tells a fascinating story that resonates way beyond its notional suburban boundaries.

As Melbourne grew, its suburbs became too vast for one local government body to administer, and areas were carved off to form separate municipalities: Richmond, Collingwood, Fitzroy, South Melbourne, North Melbourne. Carlton, however, despite periodic agitation from its residents, has remained within the boundaries of the Melbourne City Council.

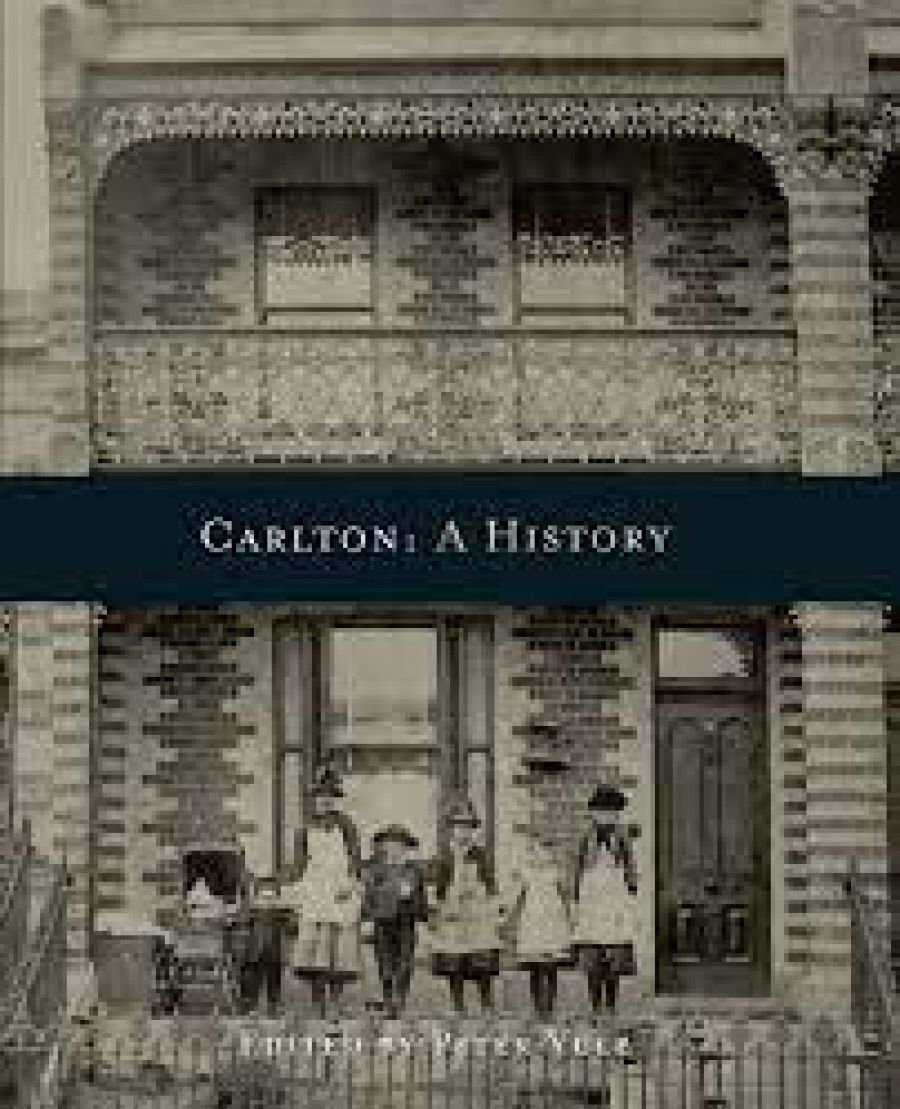

- Book 1 Title: Carlton

- Book 1 Subtitle: A history

- Book 1 Biblio: MUP, $59.95 hb, 584 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

As Melbourne grew, its suburbs became too vast for one local government body to administer, and areas were carved off to form separate municipalities: Richmond, Collingwood, Fitzroy, South Melbourne, North Melbourne. Carlton, however, despite periodic agitation from its residents, has remained within the boundaries of the Melbourne City Council.

Carlton is a swarm of contradictions. At once demi-monde and exclusive, it has been home to generations of students and academics, and the site of bitter heritage brawls between residents and the neighbouring university. Few, if any, other Australian suburbs have seen such extremes of wealth and poverty, adventurous intellectualism and brute violence. In the late nineteenth century, it was famed for its prostitutes; in 1927 the gangster ‘Squizzy’ Taylor was shot dead there, just down the road from the radical Jewish theatre and intellectual centre, the Kadimah; on the afternoon that Carlton: A History landed in my in-tray at the university, there was a gangland murder in a busy Carlton restaurant.

Fashionable in the 1850s and 1860s, by the 1890s Carlton was fast becoming a notorious slum area. The back lanes filled with cheap housing, occupied by working-class families that could not afford the cost of housing in the new ‘outer’ suburbs. Then, during the first half of the twentieth century, came wave after wave of migrants, most prominently Jewish refugees in the years leading up to World War II, and Italians in the years after it.

In more recent times the Housing Commission flats, built in the 1960s to replace the ‘slums’, have accommodated refugees from Eritrea. (For a book that has so much to say about the contribution of migrants to Australian culture, and so much about community activism, Carlton: A History is strangely quiet on the great shame of our time – the treatment of refugees from the Middle East. Their tragedy is encapsulated by the fact that this book is able, indeed almost obliged, to leave them out.)

The nominal editor of Carlton: A History is Peter Yule, but its progenitor was ‘the history committee of the Carlton Residents Association’, and the book’s weaknesses smell strongly of committee. Superb essays by architectural historians Miles Lewis, Allan Willingham, George Tibbits and Georgina Whitehead are lumped together at the end under the heading ‘The Built Environment’. But the whole darned book is about the built environment: it is largely indifferent to the natural environment. There are innumerable missed opportunities to explore the effects of urbanisation on the landscape: industrial pollution, the impact of the motor car, shifting attitudes to native flora and fauna, the protracted drought (is Melbourne becoming a desert city? how long before the word ‘fine’ has different connotations?). There is, in short, no extended discussion of the space occupied by the constructed entity known as ‘Carlton’. At its worst, this focus on the built environment descends into a tedious catalogue of the victories over developers won by Carlton residents’ groups. Yes, it is great that beautiful old buildings were saved from demolition; but this book would be stronger if it presented a more balanced account of the motives behind the developments that residents have opposed. You don’t, for example, have to believe that the university’s plans are all flawless to see that it is faced with cruel dilemmas: the use of its allocated space has changed radically since it was established 150 years ago, yet the campus is both packed with and hemmed in by ‘heritage’ buildings that it durst not alter. Something has to give. (Mayhap it will be the – heritage listed! – Baillieu Library, which has long since ceased to have room for all the books it is supposed to hold.)

Inevitably, there are minor faults as well: Frank Strahan – archivist, historian, community activist, and Gonzo-esque football commentator – died in November 2003, not 2002; Overland was established in 1954, not 1940; a directory search confirms that Markov’s Pharmacy was on the corner of Drummond Street (as stated on page 61), not Lygon Street (page 60). When you set out to explore the minutiae of community life, the details really matter: trivial errors such as these detract from the value of this wonderful book.

For all my carping, Carlton: A History is full of wonders. Slum clearances, trade unions, sporting clubs, grocery stores, theatres, bookshops, bohemian intellectuals, sober churchgoers, a transvestite arrested at the Exhibition Building in 1888 for ‘winking at gentlemen’ … all human life is here. Anyone who is tired of Carlton is tired of life.

Comments powered by CComment