- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Anthropology

- Custom Article Title: The Loss of Tongue and Tradition

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Loss of Tongue and Tradition

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

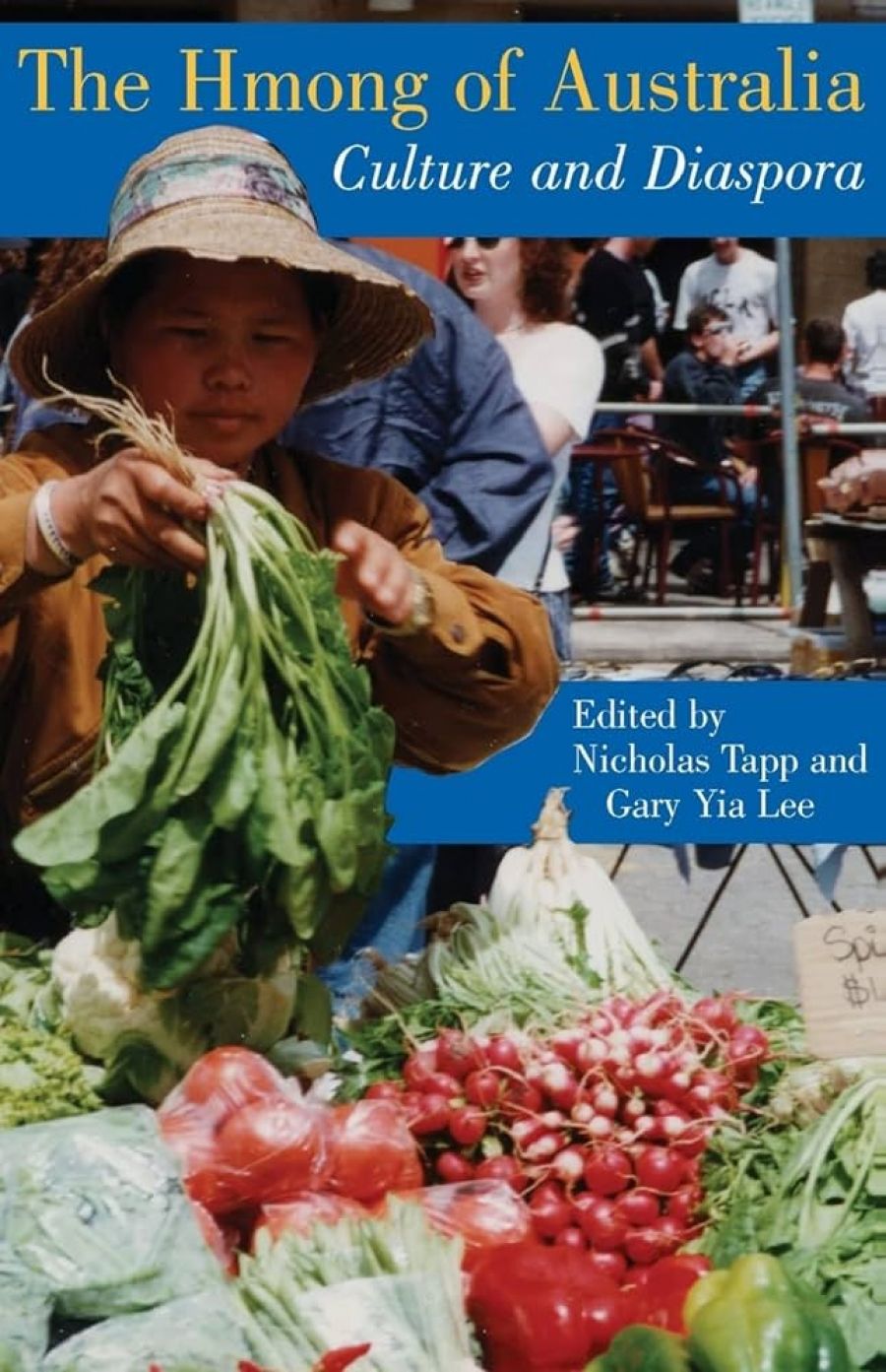

One sun-filled Saturday in spring 2000, I wandered through Salamanca market, in and around the historic sandstone buildings on Hobart’s waterfront. After a long absence, I expected the arts and crafts, antiques, and books amid tourists and the local caffe latte set. What surprised me were stalls of beautiful fresh fruit and vegetables, grown and sold by smiling ethnic Hmong. The bright front cover of The Hmong of Australia zooms into that image of my memory.

It is pleasing to learn from sociologist Roberta Julian that, for Tasmanians, the Hmong ‘symbolise a new openness to Asia’. Yet it is disconcerting to be told: ‘Insofar as the Hmong are accepted as Tasmanians, however, their identity has become commodified, trivialised and marginalised … a superficial Hmong identity.’ Any more so than that of the Han Chinese and Italian vendors, who draw camera-clicking busloads to Melbourne’s Queen Victoria Market? Or that of the colourfully clad Hmong minority in China’s southern Yunnan province, ancestral homeland of the Hmong?

- Book 1 Title: The Hmong of Australia

- Book 1 Subtitle: Culture and diaspora

- Book 1 Biblio: Pandanus, $34.95 pb, 217 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Refugees from the hill tribes of impoverished, landlocked Laos, which borders China, the Hmong are among Australia’s newest and smallest immigrant groups, and number fewer than 2000. Mostly former soldiers or subsistence farmers, they fled the communist revolution of 1975 and arrived, like the Vietnamese and Cambodian victims of the Indo-China war, via the camps of Thailand. By the mid-1980s they’d settled in Sydney, Melbourne, Hobart, Adelaide and Canberra. Yet today more than half live in Queensland, many as banana planters around tropical Cairns.

In his introduction, co-editor Nicholas Tapp, an anthropologist at the Australian National University, writes of ‘the distinctive “Hmong-ness” of the Hmong, the difficulties of their adjustment to a new society … their attempts to find new ways of “being Hmong”’. He then quotes fellow editor, Gary Yia Lee, a former Colombo Plan student from Laos: ‘“But a lot of us have been trying very hard to be Australian!” And not being accepted as such … ’ – a dilemma faced by many Australians of Asian descent.

The first Hmong PhD in anthropology, Lee provides an excellent summary of the Hmong position in Australia. Like other non-Anglo-Celtic migrants to the West, they are torn by the loss of tongue and tradition. Few adolescents know how or want to speak Hmong, any more than to follow the religious rituals of their parents. Just as leaders of the 180,000 Hmong in the US ponder their cultural survival, Lee asks: ‘Where will the Hmong of Australia go to from here? After the first generation, will their children still retain enough of their Hmong cultural heritage to be called Hmong. Or will they be Australian in their hearts and minds, and Hmong only in their appearance?’

It is difficult, if not impossible, to be both Hmong and Australian: as Julian points out, some Hmong practices are illegal. As an example, the use of live animals ‘to find lost spirits’ – a custom outlawed in Australia – is crucial to Hmong identity. There are also limits to funeral rites, such as leaving the body exposed for one or two days, and positioning the grave between mountains to optimise the chances of attaining a better life in reincarnation.

My mother can recall how, in Hobart in 1941, her Chinese-born father – my grandfather – was dressed in his best suit, his pockets fitted with crisp £1 notes to assist him in the afterlife, and placed in a special tin casket before being buried in a mahogany coffin. The idea was that, after the war, his body would be returned to ‘the motherland’. But when my grandmother died in 1948, she received no tin casket. Her children had become Australianised, and her body was laid alongside my grandfather’s in Tasmanian soil. Despite multiculturalism, the Hmong seem destined to bend with the winds of assimilation.

Apart from Pranee Liamputtong’s ‘Being a Woman’ – a chapter on menstruation – this book is based on proceedings at an anthropology conference at the ANU in 2002. It ‘aims to bring knowledge of the Hmong to a wider public and contribute to the understanding of these people’. The sections by Tapp and Lee will have greatest appeal to non-specialists. The others read rather like research papers presented for peer review – with an eye to academic advancement – rather than for general access. Nonetheless, even the often highly technical contributions on music and language, by Catherine Falk and Nerida Jarkey, respectively, have their place in such a university publication.

Colour photographs enhance Maria Wronska-Friend’s ‘Globalised Threads’ on the significance of costumes and jewellery to the Hmong in North Queensland. A map of Laos, surrounded as it is by China, Burma, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam, would have enhanced understanding, especially among the ‘wider public’, of Hmong history.

Comments powered by CComment