- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letter collection

- Custom Article Title: Ian Dickson reviews 'The Luck of Friendship: The letters of Tennessee Williams and James Laughlin' edited by Peggy L. Fox and Thomas Keith

- Custom Highlight Text:

The tall, handsome, socially adept if emotionally reticent scion of a wealthy, well-connected family and the crumpled, physically unimpressive, excitable son of an alcoholic travelling salesman seem to be an unlikely pair to form a long-standing friendship. For both James Laughlin and Thomas Lanier ‘Tennessee’ Williams ...

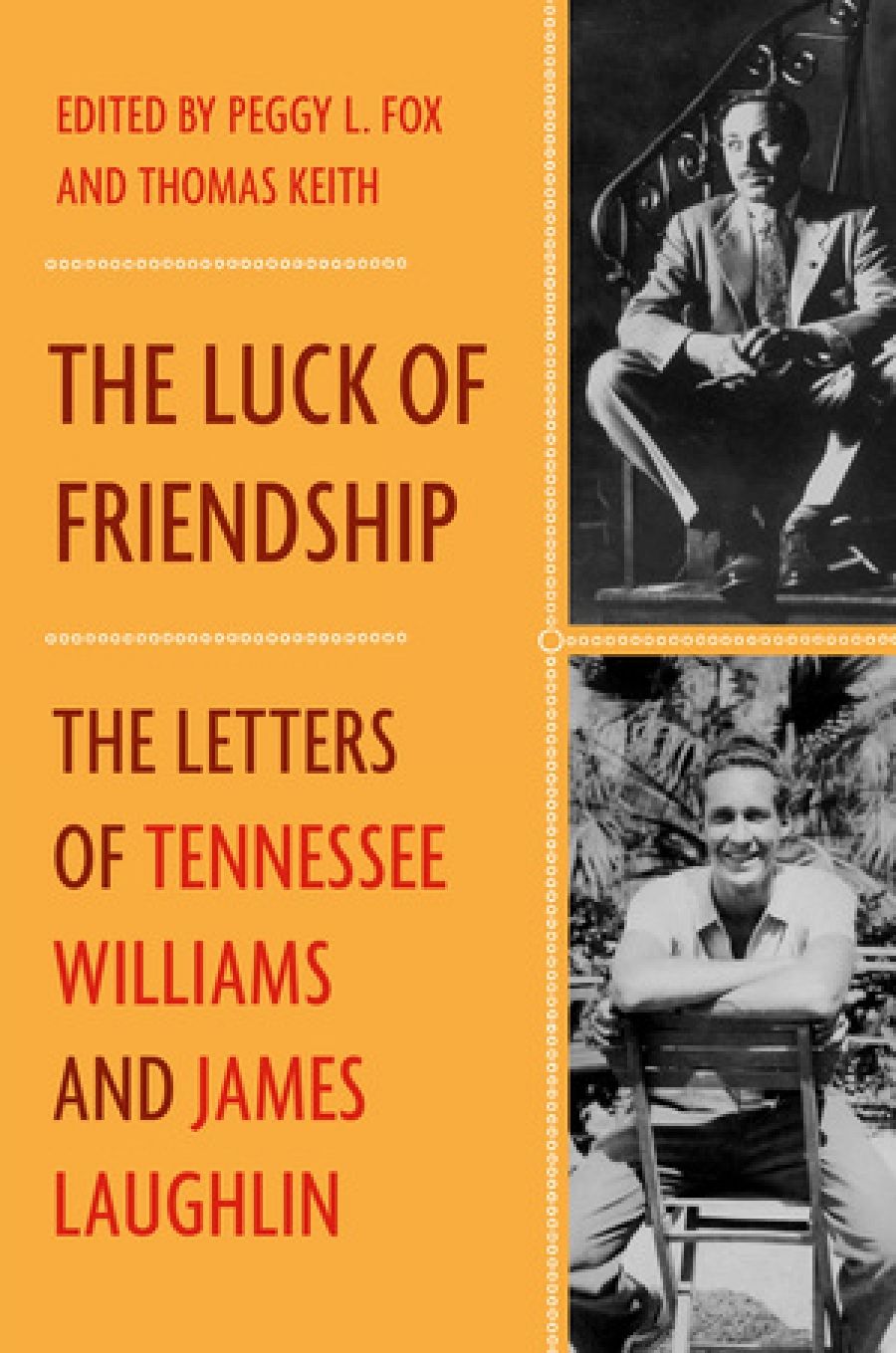

- Book 1 Title: The Luck of Friendship: The letters of Tennessee Williams and James Laughlin

- Book 1 Biblio: W. W. Norton & Company, $56.95 hb, 432 pp, 9780393246209

Laughlin descended from Pittsburgh steel royalty, a family whose connections included art patrons Henry Clay Frick and Duncan Phillips. He developed an interest in literature early and while still in his teens was corresponding with Gertrude Stein and Ezra Pound. Later he became one of Pound’s major publishers and supporters during his controversial postwar years. Laughlin’s main ambition was to become a poet. He continued to write poetry all his life, even though, in an often-told, possibly apocryphal story, he claimed that Pound advised him against it, telling him he was no poet but was probably smart enough to take on the challenges of a publisher. Laughlin may have ignored Pound’s advice about his poetry, but he embraced the role of publisher with a vengeance. As founder and director of the firm New Directions, he ran an organisation that was a hugely influential power in not merely American but world literature.

![]() Tennessee Williams in 1951, photographed by Irving Penn for Vogue (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Tennessee Williams in 1951, photographed by Irving Penn for Vogue (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

When Williams and Laughlin met, at the instigation of the impresario Lincoln Kirstein, Williams was still licking his wounds from the failure of his first major production, Battle of Angels (1940). A guest at one of Kirstein’s parties, Laughlin spotted ‘in an adjacent room this little man. He was hunched over, wearing a sweater and dirty grey pants. And I said to myself, there’s someone who needs company … I liked him right away. We liked the same poets.’ In many ways, poetry was the basis of their friendship. Although they achieved success elsewhere, it was as poets they both wanted principally to be remembered. And it was Williams’s poetic sensibility, as it manifested itself though all his works, that most appealed to Laughlin.

The correspondence between the two, edited by Peggy L. Fox and Thomas Keith, both ex-New Directions staff, runs from 1942 until Williams’s death in 1983. The editors have included brief snippets of an interview between Fox and Laughlin and – since Laughlin gradually withdrew from the day-to-day running of the company with which Williams published throughout his entire career – missives between Williams and both Robert MacGregor, Laughlin’s right-hand man, and Frederick Martin, the man who eventually succeeded Laughlin.

As well as being a fascinating glimpse into Williams at work, the letters are a goldmine of gossip and material on the American literary and theatrical worlds of the mid-twentieth century, but they are in some ways surprising. One would expect Laughlin to be the calm supportive friend, and that he is, especially during the dark later years when Williams’s plays were being mercilessly disembowelled by the critics. But for such a guarded individual, he is unexpectedly open, discussing his depressions – he was eventually diagnosed as bipolar – and admitting his insecurity about the worth of his poetry. It is Williams who becomes the supportive figure, writing: ‘This distillation of your poetry has been a great joy to me … You’ve never shown an adequate confidence in the unique quality and beauty of your work. Please recognise it and take deserved joy in it as I always have.’

James Laughlin (photograph via New Directions)

James Laughlin (photograph via New Directions)

The major surprise is Williams. With the exception of a couple of tirades obviously fired off while under the influence of either the bottle or the prescriptions of the infamous Lawrence S. Kubie, aka Dr Feelgood, one would never suspect that both the life and career of the writer of these acute, funny, warm letters were disintegrating around him. He proves to be exceptionally generous both in financial and professional terms. Among several writers, he introduced Paul Bowles to Laughlin, who responded with enthusiasm to Bowles’s work. Of Donald Windham he wrote: ‘Windham’s novel (The Dog Star) is the finest thing … the quality is totally original … it is a book that only New Directions should publish.’ A constant theme throughout the letters is Williams’s desire to provide financial assistance to young writers and to help his impecunious friends. Here he is in full flight discussing his wayward friend Oliver Evans:

He is having an operation … and I would like to be able to help him with it. I may draw on my account with you for this purpose, perhaps about $1500 … On my birthday … I took him to see Romeo and Juliet and when Miss De Havilland was delivering a soliloquy … Oliver, in the fourth row, suddenly cried out ‘Nothing can kill the beauty of the lines’ and tore out of the theatre. Later that night he called up an old lady … a dowager who is the ranking member of the Cabot clan, and told her she was ‘just an old bitch and not even her heirs could stand her!’ I think he deserves an endowment for life!

In a Festschrift for Laughlin, Williams wrote: ‘It was “Jay” Laughlin who first took a serious interest in my work as a writer … Consistently over the years his sense of whatever was valuable in my work was my one invariable criterion.’ But he made his feelings clearer still in a private letter. ‘Very briefly and truly, I want to say this. You’re the greatest friend I’ve had in my life and the most trusted.’ Williams’s final message to Laughlin was read at the National Arts Club Award ceremony honouring the publisher. Earlier that day, Williams had been found dead in his hotel room. It finishes: ‘I know that it is the poetry that distinguishes [my] writing when it is distinguished, that of the plays and of the stories … I am in no position to assess the value of this offering but I do trust that James Laughlin is able to review it without regret. If he can, I cannot imagine a more rewarding accolade.’

That afternoon, Laughlin locked himself away and composed a poem which, at the ceremony, the man who was so ambivalent about his verse recited in honour of his lifelong friend.

Comments powered by CComment